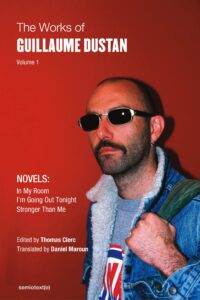

[Semiotext(e); 2021]

Edited by Thomas Clerc

Tr. from the French by Daniel Maroun

In these three autobiographical novels, In My Room, I’m Going Out Tonight, and Stronger Than Me, the controversial French writer, Guillaume Dustan (1965-2005) comes to terms with his sexuality, his sexual desires, and tests the limits of his identity through sadomasochistic sex — embodying both dominant and submissive roles. For Dustan, the construction of a homosexual identity involved a Dionysian frenzy of alcohol, drugs, and sex. In My Room goes beyond notions of good and evil in its utter rejection of puritan, heterosexual, bourgeois society, and, in doing so, Dustan is able to construct an identity. In Stronger Than Me, Dustan tests his limits through sadomasochistic sex. In destabilizing his homosexual identity — in terms of the power play practices of sadomasochism — Dustan politicizes the S&M space as one where there exists, as editor of The Works of Guillaume Dustan, Volume 1, Thomas Clerc, writes, “a democratic quality of sexual activity that did not assign defined places to its subjects.” Another transformative space — where the “I” becomes the “we,” where the singular gives over to the plural, and there is a sense of solidarity — is on the dancefloor at a nightclub. I’m Going Out Tonight is devoted, in its entirety, to a single long night at a club; a place where Dustan abandons himself to the beat of the music and experiences a sensory release, dancing with all the bodies next to his own, and in doing so, he is able to momentarily forget, at the time, the death sentence of AIDS.

In My Room, Dustan’s first autobiographical novel, is uncompromising, and has nothing to do with bourgeois conceptions about “art.” Dustan writes: “I gave him my number and told him that I was always up for narcissistic activities, then I was rather negative regarding all that was “art,” I told him I didn’t give a shit about art. This snobbish asshole asked So what you into? I’m into the fuck of the century I said.” His fearless use of the first person attacks the false bourgeois notion of literature and problematizes the idea of an uncomplicated experience of pleasure. In this first text, Dustan manages to not only construct his identity but begins to test its limits — a practice he takes into his other works — writing through the “I” as a pornographer, rather than as an elitist author who distances himself from his prose. Thomas Cleric writes:

The “I” that appears in In My Room, which is closer to an amateur porn video than to ‘home sweet home,’ rejects intimacy, opting instead for the rawness of sexual representation. For that matter, the term ‘representation’ is imperfect, and we prefer the term ‘action,’ as if Dustan were emptying sex of its human dimension in order to substitute the immediacy of pure presence.

It is through sex that he shows his defiance of the straight world, its nuclear family values, and puritan ethics. As a result, his homosexual identity, as well his HIV-positive status, and his desire to continue practicing unsafe sex, alienates him from the gay community during the time of late 80s, early 90s when AIDS was robbing so many of their lives. He was criticized by the supporters of Act-Up who, in light of the large number of deaths in the gay community, published pamphlets urging people to practice, as well as educate themselves and others, about safe sex. But, for Dustan, sex was a way of focusing his attention on something else, of clearing his mind of thoughts of his mortality. He writes:

But tonight, with the quarter tab of acid, the coke I did, and all the joints I’ve been smoking, I’ll be able to take it, and I know that an incredible feeling awaits me, every bit as mind-blowing as a parachute jump or a deep sea-dive. I like strong sensations.

But endless nights of cruising in clubs and parks, the danger and potential violence of a world of sex with many different men, often strangers, reveals in him a desire for love: “I told myself I no longer knew what love was. I didn’t want to be on my own. I didn’t want to have to go out searching for someone anymore. Stephane would eventually acquire the qualities he was lacking, and I would love him.” But this is a dream that will not be realized nor fully explored in this trilogy of texts; instead, the excitement and thrill of pleasure cause Dustan to re-enter the nightclubs, in a frenzy of drugs and sex, to the sound of Trance music.

For Dustan, the Greek gods, Eros and Thanatos, are entwined in the act of sex because for him and many others of the gay community during the HIV and AIDs epidemic, danger was always present. As a result, Dustan harbors a lot of anger and fear, mixed with desire, which at times manifests as a want to die or to kill another man: “I tell Stephane, Quentin’s right, I do want to kill him. Maybe I’ll want to kill you one of these days. That way the last thing you’ll see before you die is me. I love you I kill you.” Furthermore, he writes, “I tell him I want to kill everyone in the world, smash all the toys, stay all alone in the blood and scream until I die.” This is as much an attack on bourgeois values as it is the desire to confront his own death sentence with total abandon. Dustan is haunted by the very real experience of having the AIDS virus and the intensity with which he seeks out new sexual experiences contains the desire for oblivion. Finally, as a result of his first autobiographical novel, he begins to realize, and this gives him courage as a gay man, that “[he] live[d] in a world where plenty of things [he] thought impossible are possible.”

For Dustan, the nightclub was a kind of sanctuary away from the concerns of daily life; during the daytime he felt people acted falsely, and hid their fears or actual desires under a mask of civility and restraint. I’m Going Out Tonight takes place at the Gay Tea Dance, a dance party in the French nightclub, Le Palace. Reading this book, I was initially reminded of all the clubs I went to in the late 80s, early 90s, and all the records I listened to: new wave, soul, house, trance. Reading the book, I felt the sweat, the lights burning my skin, the dizzy feeling that overcomes you when you’re out of control and moving to the beat; you’re rubbing against the skin of strangers, everyone is alive and you’re caught up in the swirl of the sounds and the bright lights. It was solidarity within the promise of night — the “I” becoming “we” on the dance floor. This was the realization of a utopia on the dancefloor, where the dancers dissolved into a mass, united in a single cause, which was pleasure in action. As Dustan recognizes, it’s the day, a time when routine, work and daily activities take hold, that we feel separate from each other; and it’s the night that dissolves the lonely façade, allowing us to squirm in unison until dawn. In a nightclub, one can be free, one can act out one’s fantasies.

In I’m Going Out Tonight, Dustan writes, “I head down to the arena. I walk to the middle. I dance pure disco-freak style. Rolling my hips, clapping my hands. It makes me laugh. I feel light. Balanced. Suffering is unimaginable.” This experience is preceded by a moment of internal peace in the club; Dustan is beginning to feel the effects of Ecstasy; he sees “nothing on the horizon but two couples, lovingly glued to each other.” It is a rare vision of the possibility of love. Then he closes his eyes and the next several pages in the text are blank, as if this vision of love emptied his mind of all thoughts of death, of suffering, of pain. Until finally, opening his eyes again, he enters the dancefloor and has the thought that, for this moment, in this almost sacred space, it was impossible to imagine suffering.

In the third text in the trilogy, Stronger Than Me, Dustan destabilizes his identity by engaging in S&M, playing both submissive and dominant roles. He establishes a space where identities remain fluid; he is both master and slave, and the experience of “pleasure” itself is problematized — in his essay, Sex and Terror, Pascal Quignard suggests that “pleasure is puritan.” The text begins with Dustan’s “coming out” as a gay man followed by his initiation into the world of nightclubs and gay sex. In these beginning pages, Dustan draws a clear distinction between behaviors that are accepted by the bourgeois society he grew up in and those that are rejected: Dustan, whose real name was William Baranès, was educated at a prestigious university and was a tribunal judge at the time when he wrote In My Room.

At sixteen years old, he wanted “to know what sex was like. Sex was stronger. Stronger than fear.” He goes down to the Gardens of the Trocadéro, a place of homosexual cruising in Paris, and has sex with a man he meets there. But at this time in his life, he is ultimately not free from the desire for acceptance:

In an interview, Joe Dallessandro explained that he liked big and strong guys who would fuck him and vulnerable girls who he could screw. I followed him to the letter. I didn’t want to stop enjoying the wave of approbation that welcomed me when I entered a restaurant with Claire or Laurence or Nathalie, which wasn’t there when it was Herve or Frederic or Christophe. I didn’t want to blow my chances. I was made to succeed. To have a beautiful and intelligent wife, with a good name and a good family…So what if I had to lie…Say nothing to be accepted.”

Stronger than me will chart Dustan’s path from maintaining silence about his desires and putting up a false façade, to exposing everything about himself, through a relentless self-exposure; despite the rejection by the mainstream homosexual community, this allowed him to be, nevertheless, finally free.

An older and more experienced man leads the young Dustan, the initiate, into the mysteries of gay sex; eventually, he goes to the sex clubs without his guide and immerses himself with wild abandon into the world of gay sex, which eventually, in this text, leads to explorations with S&M. He sees himself as an apprentice, gathering knowledge and experience in this particular area and learning what it is to live as a gay man. Day after day, he goes on the Minitel, the early French form of the internet, and arranges meetings, seeking sadomasochist adventures with different men – sometimes with multiple partners at the same time, either old or young. S&M was, as Clerc writes, “a sexual enterprise that considered itself both a vitalist response and a flirt with death.” As a result of these experiences, Dustan transcends even his identity as a homosexual; he prefers the term “homosexual” instead of “gay” – he hated the word “queer.” The word “homosexual” dates back to 1869, and Dustan perceived it as a medical term used to monitor as well as punish those who were thought to be “different.” Stronger Than Me is probably the toughest book in the trilogy. It’s the hardcore version of In My Room within which Dustan explores the potential extremes of gay sex: bondage, fisting, and golden showers; and he does so with an anarchist spirit, reminiscent of the gay world in the 1970s. Thomas Cleric writes, “Dustan refused to desexualize homosexuality (as a certain queer tendency would have it) but it was through sadomasochism that he would, little by little, free himself from his identity.”

The three works collected in this volume focus on the body; their emphasis on sex, often of the extreme variety, is Dustan’s attack on the, as Clerc writes, “very controlled world of turn-of-the century French literature,” that had been “overcome, like the rest of society, by a wave of nihilism, melancholic cynicism, and ridicule linked to what can only be called a negative version of postmodernism.” For Dustan, the acceptance of the hetero-normative life is deadly to experience. His work is, as Paul B. Preciado writes, “intimate and ferocious at the same time, dazzling and unapologetic.”

In his prose, Dustan exposes himself and his sexual practices to such an extent that his literature has the potential to disturb a reader. A reader may not be familiar with such relentless self-exposure in writing on sex, especially gay sex; such extreme visibility is only possible in porn and rarely, if at all, is it handled effectively in gay fiction, without falling into the trap of being erotic or being in some way romanticized. Normally there is a safe distance between the reader and the work, however transgressive it is, whereas in Dustan’s writing the language is intimate, precise, explicit, pornographic even, and yet, ultimately, an attack on what is known as “Literature”. Such as, in I’m Going Out Tonight, where Dustan recalls his first time in a gay nightclub: “All these people, hundreds and hundreds of guys dancing, in the back there were dozens, beefy, shirtless or wearing white tank tops, like wallpaper. I thought – This is Dante’s Inferno, and I rushed in.” I’m Going Out Tonight, like the other texts that make up this trilogy, is an invitation: abandon all hope, dear reader, and let Guillaume Dustan be your guide.

Peter Valente is a writer, translator and filmmaker. He is the author of eleven full-length books, including a translation of Nanni Balestrini’s Blackout (Commune Editions, 2017), which received a starred review in Publisher’s Weekly. His most recent book is a co-translation of Succubations and Incubations: The Selected Letters of Antonin Artaud 1945-1947 (Infinity Land Press, 2020). Forthcoming is a book of essays, Essays on the Peripheries (Punctum Books, 2021), and his translation of Nicolas Pages by Guillaume Dustan (Semiotext(e), 2022). Twenty-four of his short films have been shown at Anthology Film Archives. He is presently working on editing a book on the filmmaker Harry Smith.

This post may contain affiliate links.