Born in Kenya, she’s traveled all over and lived several lives—as a journalist, filmmaker, screenwriter, novelist, medic to the local Masai community. On paper, her experiences feel somewhat intimidating, but Melanie Finn couldn’t be more accessible and warm. Within minutes of her popping into the Zoom room, we were deep into a discussion about Africa, the Upper East Side, and then her theories on “The Undoing” (as of writing this I finished and she had two more episodes to go). Finn’s third novel was published on January 26th and, although it’s hard to believe she could top her previous novels The Gloaming and The Underneath, The Hare is by far her best work to date.

The Hare is an affecting portrait of Rosie Monroe, of her resilience and personal transformation under the pin of the male gaze. Raised to be obedient by a stern grandmother in a blue-collar town in Massachusetts, Rosie accepts a scholarship to art school in New York City in the 1980s. One morning at a museum, she meets a worldly man twenty years her senior, with access to the upper crust of New England society. Bennett is dashing, knows that “polo” refers only to ponies, teaches her which direction to spoon soup, and tells of exotic escapades with Truman Capote and Hunter S. Thompson. Soon, Rosie is living with him on a swanky estate on Connecticut’s Gold Coast, naively in sway to his moral ambivalence. A daughter — Miranda — is born, just as his current con goes awry forcing them to abscond in the middle of the night to the untamed wilderness of northern Vermont.

Almost immediately, Bennett abandons them in an uninsulated cabin without a car or cash for weeks at a time, so he can tend to a teaching job that may or may not exist at an elite college. Rosie is forced to care for her young daughter alone, and to tackle the stubborn intricacies of the wood stove, snowshoe into town, hunt for wild game, and forage in the forest. As Rosie and Miranda’s life gradually begins to normalize, Bennett’s schemes turn malevolent, and Rosie must at last confront his twisted deceptions. Her actions have far-reaching and perilous consequences.

An astounding new literary thriller from a celebrated author at the height of her storytelling prowess, The Hare bravely considers a woman’s inherent sense of obligation – sexual and emotional – to the male hierarchy, and deserves to be part of our conversation as we reckon with #MeToo and the Brett Kavanaugh Supreme Court confirmation hearing. Rosie Monroe emerges as an authentic, tarnished feminist heroine.

Given the timeliness of this subject matter, I was especially interested in asking Finn about the trickier character struggles she paints in the book—particularly around a woman struggling to come to terms with modern feminism in all its forms.

Katie Rainey: I won’t say anything, but when you finish [“The Undoing”], can you just send me an email and tell me what you think?

Melanie Finn: I will. I think it’s got to be Donald Sutherland. There’s a reason why he’s in this production. He can’t just be, you know, Nicole Kidman’s dad.

I’ll say that my friends all loved it, but I was a little bit mad about the outcome. I have a bunch of questions about The Hare, but we can always come back to “The Undoing.” Well, normally I wouldn’t ask this question of a work of fiction, but after watching that interview with you and Eric [Obenauf, her publisher at Two Dollar Radio], in which you talked about the true story behind The Gloaming, I was curious—is there a true story behind The Hare?

Let me think. I definitely picked stuff out of the local papers and there were these murders that happened on the interstate at the time, but crucially I was going through menopause at the time and that’s a real pivot point in life for women. You have menstruation and then you have this end of everything that has sort of—to that point—defined you as a woman and it’s actually really empowering, even though you feel like hell for four or five years, and you just want to kill people and you sweat and it’s like your body is doing everything possible to make you really unattractive, but then you kind of come out the other side of it and you get to reinvent who you are and you feel this tremendous freedom from that. I look back at pictures of myself when I was younger and I can admit I was really beautiful. But I was also so stupid and clueless and caught up in what it meant to be beautiful. This is related to men because of how I looked and this enormous amount of energy that was expended in that direction.

And lastly, you know, I was sexually abused as a child and I took a really long time to be able to write about it. I often find that I can’t write about a place until I’ve left it. And I think that that’s how it was with my childhood abuse. I really had to feel like I left it in order to be able to write about it and feel like… what does the other side of it look like rather than what does this feel to be still all mixed up and mired in this.

Wow, I didn’t know that.

Yeah. And well, there was the whole thing with Christianne (a trans woman in The Hare that the main character struggles to at first understand and accept). I actually did have that happen to me. A producer who I’d worked with for a really long time, years ago, suddenly reappeared in my life and had transitioned and I found myself really confused. I wanted to be happy for her, but at the same time I was just confused by that journey.

You just started talking about one big thing I wanted to bring up. The conversation around feminism right now is just so fascinating to me, especially when it comes to trans rights and seeing people like J.K. Rowling tweet these things with very TERF-heavy (trans exclusionary radical feminist) connotations. I find it really illuminating to watch people like her and like your main character Rosie really struggle with their relationship to trans women. And you just talked about this producer friend of yours, who was an influence for that part in the book. I’m really interested in that moment near the end of the book where Rose struggles with that news. Was that the struggle you were talking about that you had? Or have you seen that in other women you’ve known and wanted to write about that?

It was definitely my struggle. I think part of me was scared for her. Like, how could she be sure that this was what she wanted? Because the surgery is so invasive. To do that was shocking to me. You know, it’s not putting on certain clothes, it’s cutting things off. So, I really struggled to understand at that moment. But then I spoke to a friend, she used to be one of the world’s leading ballerinas, but now she’s a writer and so she is very much more part of that world. And she told me that friends of hers who had transitioned felt nothing but relief. They felt an enormous sense of relief when they inhabited a new body, and I just thought this has nothing to do with me. If this is what someone needs to do to feel relief, then they should do it. It doesn’t take anything from me. I have tried to understand a little bit where J.K. Rowling is coming from. We get very nervous to talk about this, to put a foot in the wrong place. Some of the things she said I’m like, okay, I mean, maybe there’s a sense that somebody is trying to shoehorn in on what it means to be a woman. But at the end of the day, I do think as a writer you approach anything from the human experience, regardless of what your body is. You’re always looking for what happens to humans, whether you’re white or black or trans or straight or racist or not racist. This is the skin we have and we all have these experiences underneath all of that, and as a writer, that’s where you want to be digging around. That’s where change happens anyway.

I think that is a really brave thing to not only write about—your struggle in this moment, essentially. Part of it is fictionalized with Rose. She’s her own person in the book and it becomes her own struggle. But to not only insert this thing that you really struggled with—especially at a moment where so many people are publicly struggling with it in not-so-graceful ways and facing a lot of backlash for it—and then to come and talk to me about it. I think that’s pretty brave. Are you worried about criticism at all?

Well, you know, there’s always somebody who takes issue with something in your work. People will always find these particular meanings, no matter what your intention was. Someone will find something that they want to pick out or that they latch on to. With my character Christianne in The Hare, initially I just had it be this person Chris from her past, and I couldn’t quite resolve it that way—he was just a man from her past. It didn’t go deep enough into the struggle that Rose was going through as a woman, and then I realized that what she feels is that she wants the clarity of self that Christianne has. It has nothing to do with being trans or leaving a wife/family or whatever. What Rose is really envious of is Christianne knowing exactly who she wanted to become and becoming that person.

When we go through menopause, we do reach that point where we’re like, okay, I’m halfway through my life, if I’m lucky. Who do I really want to be for the next part of it? Because you come to this moment in your mid-life with all this experience and all this data and you actually get to choose who you want to be. When you are 19 or 20 or even 30, you don’t know shit. You think you do. And I think if you’ve had really strong formative experiences like abuse, a lot of that you don’t get to make choices over who you are and you still struggle with the way to deal with that. But by the time you reach your middle age, you’re like yeah, I think I can choose from here on out who I’m going to be for the next part of my life, and that is incredibly liberating.

Thinking about the structure, in the past I’ve heard you talk about “life rearranging itself” and it seems like that’s kind of how the book is. Can you talk about how this idea influences your work?

“Life is courage, it will arrange itself.” That’s a quote from a very famous French photographer. I can’t remember his name, but he was a contemporary of Brassaï. He and his wife were perennially broke and getting thrown out of crappy little studios in Montparnasse and they were having to move again because they had no money. And they’re sitting on their suitcases in the hallway. She’s in tears, and she remembered later him saying, “life is courage, it will arrange itself” and it did, it did. So I think for Rose, in the end—spoiler alert—I think that she has the courage to really believe life will arrange itself again.

Yeah. And in the end, it’s kind of like the first time she’s really arranging it for herself. Up until then, other people had arranged her life for her. That’s also something that came to mind while I was reading. I don’t want to call it an intentional feminist structure, but as I was reading through The Hare I kept thinking, okay, whatever climax is going to happen is going to be around Bennett—the man she becomes involved with. But while there was a climax with him, it wasn’t the climax, there was a whole other book entirely after Bennett… I’ll just say “exits” the book.

Yes, exactly.

Did you go into this thinking that the structure would be Rosie’s whole life in 300 pages?

I can’t quite remember. I think that I initially thought that I would tell it in flashback. But I find flashbacks can be really ham-fisted and you never feel like you’re authentically in one place or the next. I’m also aware that I took a huge leap in the last part of the book and one critic has already said that act is a mess. Of course it’s a man—[laughter]—I definitely think this is one of those books that women tend to like more than men and it’s funny because I didn’t mean to shoehorn in all this, this life. And yet, Eric pointed out that it does work that way. Somebody else pointed out that it’s like an evolution of feminist thought. Maybe that was you. Was that you, Katie?

Haha, it could’ve been me. I wrote a lot about that.

But I do think that it is a story of actualization, of moving away from that horrible sense of obligation that is thrust upon women. Maybe not so much for your generation, but certainly for my generation, and my mother’s generation and back in time, in all these subtle ways. And I understand that’s how racism works too. It’s this subtle stuff that’s going on all the time like a drip drip drip and you come to a place where you are like, I’m done. I’m done with that. So it is a progression. If you’re lucky, you get to make that progress.

Yeah, to me, that’s one of the really lovely things about the book. You have these steps with Rosie along the way—as a child, young adult, adult, and beyond—and each step is a moment of transformation that illustrates, too, a progression of feminism through her struggle. And I really loved the ending, it was so unexpected. So I just want to say fuck that critic who said the last part of the book is a mess, because I was so pleased that it did not go where I thought it was going to go.

I mean, I didn’t start out thinking, okay, I’m going to write this feminist art. I did start out essentially from that personal perspective of, okay, I was this abused child and then became this young woman and I made really bad decisions. Because, honestly, I didn’t have good support. I look at my daughters and I realize that even with the kind of support they have, they’ll still make stupid decisions, but they won’t make decisions as stupid as I did. Someone like Rosie, she really didn’t have any good guidance in her life at all. She was completely isolated and completely alone, there was no one to hold her hand and say, look, maybe give this a second thought. She’s grasping desperately all along. I did give her these sort of mentors—the art teacher, a woman in the parking lot outside the abortion clinic, and even the character Hobie at one point. But she’s so desperate for a connection and all she has is Bennett, who’s a ghost, really. I mean, he’s not there for her.

Funnily enough, I did have one friend say that she thought there was another book about the relationship between Rosie and Billy that really interested her and she was really upset by what happened to Billy because she wanted to explore that whole relationship and how it evolved. I wish I was that writer who could unpack that relationship on that micro level. Some people are really good at those detailed relationships. But I’m not, I need to have too much plot happening [Laughter].

I would almost disagree with you there—about Billy and Rosie’s relationship. I mean I have relationships like that where there doesn’t need to be this grand, intellectual unpacking of what’s happening between us. You just kind of move in sync. And that seems to be what was happening with these two women. To me, it almost felt like a subversion of how we see women often interacting with each other sometimes in literature. Like they’re skinning this deer and learning to build and make stuff and work on this house together. I really enjoyed seeing that relationship unfold organically between the action.

Yeah, I did too. I love Billy. Billy’s inspiration came from—I lived in the California desert for a long time. So I got to know quite a few “Billies.” One in particular, who was actually a man, gave me the space to feel safe and I think that’s what really gets to Rosie in the book—finally here’s someone who’s got her back. That gives her an enormous amount of strength. It not only allows her to survive, but to thrive because here is someone, at long last, that is actually there for her.

There’s also just so much happening in your language. There’s a kind of cinematic quality around your language. I know that your husband’s a filmmaker and you’ve made films together. You’ve written for TV before too. I’m wondering if you can talk about that influence. I mean, the book played out like a movie in my head.

Yeah, so, let’s hope that Reese Witherspoon thinks that too. [Laughter]

It’s HBO’s next “Big Little Lies.”

The visuals are really important. I know one of my skills is in description and creating a strong sense of place, creating that atmosphere. I really enjoy doing that. And I think about the words that I can use to create that sense, and for Rosie, she talks a lot about smell. Her sense of smell is hugely important. She’s always mentioning the smell. Up here [in Vermont], I’m really aware of the smell of different seasons and the smell of different trees and all of my horses smell different. So, I wanted to bring that into it to create an idea of this person who really does have an artistic sensibility. She’s sort of like Virginia Woolf, who wrote in that hyper sensory kind of way. I’m not doing that, I’m not Virginia Woolf. But people always come to me and say, ‘oh, I know exactly the house that you are writing about here’ and it’s like, no you don’t because I made it up. But because it’s become so real, the way people read it, they’re convinced they know exactly where it is. I think that is a good thing, and it’s a pleasure. It’s one of the pleasurable parts of writing for me. It’s playful, rather than the horror of trying to get your characters to interact with each other and talk to each other in a way that feels authentic.

Yeah, it speaks to that idea of the specific becoming the universal—somebody attaches themselves to a detail and they think, ‘oh, I know that house because I’ve seen it somewhere else.’ And speaking of the language, you said you’re not hyper sensationalizing like Virginia Woolf. The language in The Hare is very clean, even when going into the most gritty details, nothing is superfluous. I’m just kind of wondering how many drafts that takes you or if that is just your talent—that it just comes out that way?

I think it’s probably a combination of both, and aspiring to be like writers who I really enjoy. Early on I loved Bruce Chatwin, who is now sort of forgotten as a literary hero, but I would read his writing and be amazed by how he could create this sense. And yet, if you try to deconstruct his sentences, they were just normal words, but somehow they added up to something that felt extraordinary. There was a magical quality there and having been a journalist, one is trained for the economy of words and also as a screenwriter you don’t have a lot of time to set the scene, you have to really pick your words. I also worked with a fantastic editor on The Gloaming who was ruthless and went through and took out lots and lots and lots. I think I’d used the word ‘little’ dozens of times without being aware of it and she just went through and circled them all. It just made me really aware of those tiny habits. And, you know, I’m a Scott, so I like economy and I really resent long worded books. It’s like the director’s cut of a movie that’s three and a half hours long. Well, it needs to be really, really, really good if you’re going to make me sit down for three and a half hours.

So does that mean you are or are not a fan of Cormac McCarthy?

I love Cormac McCarthy, but I cannot be McCarthy. He’s doing something completely different. Right? He’s like Hemingway. You’re creating something entirely different with words. And I think I went through a stage of trying to mimic Cormac McCarthy. Probably every writer does. It’s like you go through your McCarthy phase and then maybe Joan Didion thrown in there. And then after a while you realize none of that fits. Those people are stylists. I love reading that, they’re amazing stylists. But at the end of the day, none of those are particularly long books. I did just read Anthony Trollope’s The Way We Live Now. It’s 800 pages, but it’s really good. It’s like episodes of “The Crown.” You get into bed every night like “what’s happened?” It’s a soap opera, fun soap opera reading. It’s not like sitting down to read McCarthy. It’s just a great read, a great story.

I mean, the language is entirely your own, in The Hare. I love The Gloaming, but The Hare has like…you just keep going deeper and deeper into your style, into your own language. I think I thought of McCarthy because when Rosie was in that cabin with Billy in the woods, there was an air of him in the back of my head. Maybe because it was just so dark, what with that man that comes around trying to take pictures of her daughter. I think that’s why I ask about McCarthy.

Well, that’s a real, real compliment. I love the elasticity of words and how you can put them together to create things. It’s like a big LEGO set.

Yes. It’s also just kind of unbelievable how much you’ve packed into this book. All the different themes. While there is this overarching theme of the progression of feminism that we talked about, there are all these other things and the book is only 300 pages, but it does not feel stuffed or overwrought. It feels very organic. I don’t know if that was something that you struggled with while putting it together?

You know, Eric said the same thing. I guess my fear is does it feel too shallow? Does it feel as you said over-stuffed, but people don’t generally seem to find it that way. I’m not quite sure why it worked out that way. Did I just get the right sections of her life? I can’t answer why that works.

There is a wonderful book that I have had in the back of my mind. The Ginger Tree by Oswald Wynd. It’s an older book about a woman who lives in China. She falls in love with the Japanese Ambassador or he’s a diplomat of some kind, and they have this passionate affair. She ends up getting pregnant and moving back to Japan with him and it spans 40 years of her life or something. The ending is one of the most beautiful, heartbreaking endings of any book I’ve ever read. I wanted that at the ending of The Hare, even though they’re totally different stories. I wanted to walk out the door with that feeling of being full, even though it’s empty. Does that make any sense at all? The Ginger Tree by Oswald Wynd. Highly recommend it. It’s a beautiful story.

You also write a lot about isolation in all of your books. Everyone’s very isolated. I’m wondering what your relationship with isolation is like? Is that something you think about a lot? And if so, is this pandemic just driving you crazy?

It’s really interesting because I was actually thinking about that the other day. All my characters are these crazy, lonely women.

That’s the title of this interview now: Crazy, Lonely Women. [Laughter]

One of the things that strikes me is when I dream. In how many of my dreams I’m alone, like I’m alone in the airport and I’m trying to get to the gate, but I can’t find my bag. But my life is full of people. I love my husband, I have my kids. I’ve got friends, but for some reason, in my subconscious, I’m intensely alone. I think there was a large period of my life, my 20s and 30s, where I was very alone and I traveled a lot. I love my solitude. I’m definitely one of those people who’s just really happy being alone. But there’s something about the subconscious. I think maybe our deepest struggles are always very isolating. We struggle with who we are and how we want to react and who we want to be. And that’s ultimately an incredibly lonely journey. You can only decide yourself who you’re going to be. People can’t change you.

That’s a really interesting point. I’m now in the back of my head cataloguing different books that I love and recognizing there is a theme. I mean, David Mitchell. His whole thing is our connections between each other, so isolation would have been the scariest thing. Maybe it is just a human fear of not being connected to each other. We’re social creatures.

That’s very much what I was reaching for in that last part of The Hare. It was kind of a combination of conscious and unconscious, but I wanted people to feel like Rose had connected with people, to see she had a life. She had a job, a friend. She was part of a book group. She thought about things. She wasn’t just this isolated person, she had created a life for herself in this place. The business of her life, I wanted it to feel full. I didn’t want that sense of real isolation that she’d had as a young woman. I wanted it to feel really different in the third part of the book, like she has done something with her life. She did come out of her shell.

This book is incredibly timely. When did you start writing it?

Oh, I started writing it right around when Trump was elected, and I was just in a state of fear. I remember, I went to have coffee with a friend who was in tears, asking why men hate us so much. There was just a deep misogyny that came out with the Trump campaign. How you could talk to women and talk about women and apparently nobody cared. And even now, we still live in Trumpland. Where I am now, I’m surrounded by Trumpers, and I look at them and I’m like, “how can you support this man and have daughters?” It doesn’t even compute, none of it makes any sense. So yeah, I just wrote, here’s this horrible man and he’s been rewarded for being horrible, rewarded in the biggest way you can reward anybody, being made president. That was a really heavy thing to put on a lot of women, and then we had Brett Kavanaugh. It was like, really? We have this now? It was hard for people who weren’t damaged, and very hard for women who were damaged. I think there were a lot of women who just collapsed on the kitchen floor in tears. It was tough.

But that’s what’s really interesting about The Hare. You almost play into this idea of the 53% of white women that voted for Trump, when sometimes Rosie struggles with different things. Like the idea of rape being rape, whether it is or not. She debates in her head violent rape vs. simply a man not listening to ‘no’. She struggles with that and that’s what I thought was really interesting, watching internalized misogyny play out in a character.

There were a couple of things involving Trump, because of course he’s become this amazing archetype for us all to think about. There were these old women in the south and they were all ‘Trump, Trump, Trump’ and someone asked them what they thought about the things he says about women. They said, “Well, you know, I don’t have to date him”. And I’m thinking well, first of all, he’s not going to date you. You’re 50 years too old for him. And secondly, what about your grandchildren? Your granddaughters?

I actually just had a discussion with a friend about why mothers do not protect their children from abuse, they know about it and they kind of log it off. And she said, because it probably happened to them, and so it’s too complicated or too much of a challenge to think about how it might have affected them. I was thinking about this while watching an interview with this woman in Montana or some place where Trump was campaigning. In the interview they were talking about what young girls go through and this woman said, “well, you know, boys will be boys and it’s just something girls have to learn to put up with.” And right behind her in the background is her 15 year old daughter. I’m thinking, there it is. There’s that sense of obligation. You just have to put up with it, just put up with it and move on. And how many women for frickin’ thousands of years have been putting up with it? As Rosie says, you know, you just go up the stairs and you get on with it because what are your options? To hear this in 2018 was like, this doesn’t make any sense—that women are still thinking this is okay. Your body is just a parking lot, you know, in and out, in and out. It doesn’t matter. Just go on and get the dinner done. It doesn’t matter who’s been inside your body or what they’ve done to it. There’s something fundamentally so fucked up that any mother would say that, and say it with her daughter in the background. But that’s how I was, I mean honestly a huge part of my abuse as a child came from the community. They so devalued a girl’s body that they didn’t care. It didn’t matter. It didn’t matter. And when I grew up, there were over a dozen girls who were abused by this one guy and nobody did anything and you think, okay, well that was back in the 60s. But it happens all the time now, and it’s the same thing. So yeah, a lot of the anger that I just expressed, obviously that comes out in the book.

It definitely comes out. It is a book with a very heavy feminist message. But it’s not this woman preaching, she’s a very messy character. She is not just a victim. The real time struggle that she goes through throughout the book really illustrates what you’re talking about. We’re only now starting to see these messy female characters who are just people and not like a “woman character”—a novelty, I mean. I’ve seen this in a lot of novels by women I admire. I’m thinking specifically of Ottessa Moshfegh. I don’t know if you’ve read any of her work, but in Eileen, for instance, she writes about these dysfunctional women. It doesn’t feel like it’s like, oh, this is a feminist book. It’s just a background thing to what’s happening and how this woman’s life is playing out. Does that make any sense?

It totally does. I remember when I wrote The Gloaming—which was called Shame in England—one of the things that the editor pushed back on, they said she’s very passive and you know she just follows her husband around and I thought, but there are so many women like that, particularly women who enter that international arena where they become the wife who does two years here and two years there. I remember saying to the editor, “you’re a career woman, right? You’re in publishing and you have nice clothes and there’s this real sense of independence. But there’s an enormous number of women who don’t have that confidence. And who are not living that life.” So to say that, ‘oh, she’s too passive for anybody to relate to,’ I thought, well, what? Every woman should be a perky Pollyanna? Some people really struggle.

And that’s kind of connected to your idea of isolation, where you do have these men taking these women to these places where they are isolated from friends and dropped in the middle of nowhere.

Yeah, that happens in my book The Underneath as well. It’s funny because what I’ve been watching is totally off subject, but I’ve been watching this series with my children called “I Shouldn’t Be Alive.” It’s basically these stories that are really well produced and they have these reenactments of people. There’s one on a sailboat that sank in a storm and people lived in a rubber dinghy for five days, surrounded by sharks, and several died. And then finally, the two or three left were rescued randomly by Russian sailors. It’s all these incredible survival stories, but basically an alternate name for it should be “Privileged people making really bad errors of judgment.” But in fact, the other alternate title for it could be “Men who won’t listen and ask for directions.” There’s a couple, you know it is going to be a couple and they get lost because the man’s like “I know the way, I know the way and we just have to head south and we will find the hotel,” and seven days later, they’ve gone in completely the wrong direction. It is in our culture to defer to men in an emergency situation. Like he’s a man, he must know how to fix the car, but really he doesn’t have a clue.

That’s funny. Rosie even thinks that Billy is a man at various times when she’s taking instructions from her and then only later realizes that she’s a woman. It’s funny to see what you’re talking about and just to think about that. And isn’t there a moment where Bennett is like, “I know the way” with Rosie in the car at the very beginning?

Yes, where she’s, like, let’s look at the map. But Bennett was actually a very difficult character. I had in my mind who he was, this unlikable person. And that somebody with any sophistication would see through Bennett. But of course, Rosie doesn’t have that. So she sees this sophisticated, connected, good looking man and he leads her to this place where finally she’s able to see who he is, but I also had to figure out how Bennett himself was going to evolve. He had to also change and emerge somehow.

He almost devolves.

Yes, exactly.

Literally in appearance. I mean, she becomes this sinewy, hardened, built woman and he devolves into mush. It’s really quite beautiful, the way you did that.

Yeah, they did very much shift like that and I think that part of him losing his power is because he senses that she’s gaining power and he has always fed off her submissiveness. But there’s a point where she’s not going to ask him for directions anymore and she’s taking over the wheel. For Bennett, a man who for a certain period of his life has been able to put things on cruise control—he’s got just the right background, the right clothes, the right knowledge that allows him to drift for a time, but then that stops and it’s not enough to take him where he needs to go in the next part of his life and he’s just not able to sustain it. Obviously, he’s a damaged person. It’s a tragedy. I don’t think he starts out as a bad person, but he certainly ends up as one.

Well, maybe that’s debatable. It seems at the beginning of the book that his family and friends think that he’s starting out as a bad character.

Yes, but it’s a question of, well, he’s a fuck up, like in the old days, he would be the third son they would have sent out to the colonies so that he wouldn’t embarrass the family. Even I’m not sure if he was really a bad person in the beginning or it was just a slide down. I don’t know if people are bad or they become bad or they just make a series of bad choices and then they just, they don’t have the ability to self arrest. One of the things I really love reading about in books is that nature of evil. At what point do we manufacture ourselves and our decisions become evil ones? Or are we just pre-programmed? That’s one of the great things about literature.

How are you publicizing the book in this midst of a pandemic?

That’s a really good question. We’ve got some reviews. New York Magazine is going to do a review. I actually just got a small grant from the state to redo my website and try and do some promotion, but it’s not in my wheelhouse at all. I’m really hoping the book catches on in book clubs because I think there is stuff for women to talk about and I think it does trigger a lot of conversation.

[Melanie’s daughter runs in to tell her that there’s a bear in the feed room]

Can Dad take care of it? Oh goodness, there might be a bear in the feed room.

Do you need to go?

I dispatched my husband in, you know, Rosie style so he could deal with it. Anyway, the publicity thing, I’m sort of suspicious of the whole thing. Because I think that a book kind of either catches some zeitgeist or it doesn’t. Some of the books that become popular are so crappy? You read them and you’re just like, what? And you read other books that are so fantastic, but they’ve hardly seen the light of day. I think it’s a crapshoot really. A lot of it is word of mouth, people love it and they pass it onto their friends. I still don’t know how people choose books, other than if somebody recommended it or they read a great review on it. What do you think?

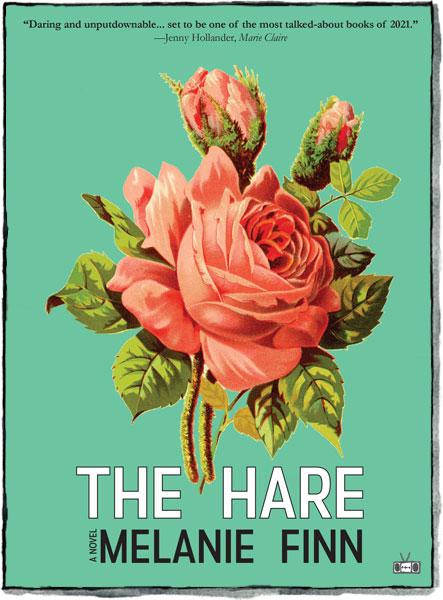

Well, I can say why I actually picked your book. I did the thing that everybody tells you not to do. I was flipping through Two Dollar Radio’s upcoming releases and I saw the book cover.

It’s so beautiful.

So beautiful. And I was just like, oh, I don’t even care what this book is about, it’s just so pretty. But then I loved it. So I totally judged the book by its cover.

Yeah, it’s a beautiful color. That’s my favorite color. And I love wild roses. What amazes me about Eric and his wife, Eliza, they’re just these incredible people. They do the publicity, they find these incredible authors, and they are raising children, and Eric also mentors young Tibetan students. And they’re happily married. I don’t know how they do it.

I was going to ask you about your relationship with them. They’re such a cool press. I know so many writers would choose to publish with them over a big publishing house.

[Daughter runs back in]

It’s an ermine!

A what?

An ermine. Weasels. They turn white in the winter. They’re very cute. Anyway, Two Dollar Radio. I’ve had really bad experiences with big publishing houses. If your book does get taken on, they give you like a week after the book comes out and then if it doesn’t explode and succeed, you never hear from those people again. And it’s really soul destroying. Plus, you have to wait two years for them to publish it after you finish writing it. So by the time they publish it, you don’t care about it anymore. Whereas with Eric and Eliza, they’re very selective and they will support that book for a year and they will do all these other things. They won’t just expect it to live on the merit of its reviews, to live or die whether it got a review in the New York Times. They’re just such great people.

They have exquisite taste. I’ve not read a Two Dollar Radio book that I didn’t like and I’ve read a lot of their books. But, two quick questions. I know you have to go take care of an ermine.

Ermine, right.

Are you working on anything now? Or are you taking some time off?

I’m actually working on this script that takes place in Kenya. I’ve been working on it for 10 years, but it’s actually finally gathering some speed and I’m working on it with a Tanzanian writer. It’s a crime thriller set around the theft of some ivory. So that’s cool because it’s different, and it’s not so quiet, so sort of internal. It’s not quite so isolating, it’s very much out and connected. I do have another book in mind. But it is intense, as you know, it’s like this intense process. It’s a really lonely experience and it’s a lot of sitting.

Well, we will tag Reese Witherspoon when we post this interview for both The Hare and this script.

Yes, and you know, Reese and her daughter are just perfect for Rosie and Miranda. [Laughter]

That’s true. Oh my gosh. Okay, the last silly question I have is I heard you say that you were reading The Brothers Karamazov. Did you finish it?

I did. And I’m one of the only people I know who’s finished it.

I love that book. “Everything is stupid!” One of the best lines in literature, when Ivan is in the courtroom. What did you think?

First of all, I think I only persevered because my brother-in-law claimed that he had finished it, and I’m not going to be outdone by Joe. So I knuckled down and finished it. I have to admit, there was a whole middle section about God that I just kind of skimmed because I’m just not interested in God. I loved when it got into all this torrid relationship between these brothers and these women and the servant and the horrible father who is like this Trumpian character. There was even a line in the book that describes the father and I’m like, look, you see Trump exists in literature. And then, actually, if you read the Trollope book which is also another 800 pages, but much easier to read, there’s another character who also fits the description of Trump. So it made me feel better because I thought, okay, he’s actually an archetype, this isn’t something new. We don’t have to be afraid of it, because it’s not new. This has been around since Dostoyevsky, this kind of asshole. So it’s okay, we’ll get through. And so far, we might…

…live in a time where we don’t find Trump in every book that we’re reading. [Laughter]

Right, right. I just read a wonderful book called The Flight of the Maidens by Janet Gardam and it’s like the anti-Trump book. There’s no Trump character in it at all. And you just revel in the gentle unfolding of a beautifully written story about a young woman, and you get to the end, you’re like, God, thank you.

I’ll have to check that out. Well, thank you so much for all this time. For sitting with me and just chatting. It’s been my pleasure, really.

Well thank you, Katie, and for liking The Hare. And now I’m going to go down and see this ermine in the feed room.

Please send me a picture!

I will, I’ll send it to you.

[She did!]

M.K. (Katie) Rainey is a writer, teacher, and editor from Little Rock, Arkansas. She is the winner of the 2017 Bechtel Prize at Teachers & Writers Magazine, the 2017 Lazuli Literary Group Writing Contest and the 2018 Montana Award for Fiction from Whitefish Review. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Lit Hub, Writer’s Digest, The Collagist, 3AM Magazine, and more. She co-hosts the Animal Riot Reading Series, and is the Co-Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Animal Riot Press, a literary press that strives to collaborate with writers to create work that matters. She is also the co-host of the feminist podcast Rosé All Day Anyways. She lives in Harlem with her dog. Sometimes she writes things the dog likes.

This post may contain affiliate links.