This essay was first made available last month, exclusively for our Patreon supporters. If you want to support Full Stop’s original literary criticism, please consider becoming a Patreon supporter.

On March 10, 1980, a 56-year-old woman drove five hours north in rainy weather to the upscale hamlet of Purchase, New York, and there four times shot a 69-year-old man, most famous, prior to his infamous death, for authoring a bestselling diet book that he, a cardiologist, had expanded from a two-page handout pressed upon patients. The cardiologist/author had, and made no pretense not to have, a “wandering eye,” often expressing a disdain for fidelity, and a belief in the interchangeability of female companions in his bed. He was a man known to be fond of the quip “women are like streetcars.” With equal transparency, the woman, Smith College alumna, magna cum laude graduate in economics, divorced mother of two, then-current head of an exclusive boarding school for girls in Virginia, proclaimed (repeatedly) that the sole joy of her existence was the sporadic attentions bestowed upon her by the celebrity physician. On March 10, after reaching his house on Purchase Street, her destination, she entered the premises through the unlocked garage, made her way up an unwieldy spiral staircase to the doctor’s bedroom, carrying a re-gift bouquet of daisies, a loaded .32 caliber revolver whose trigger required fourteen pounds of pull pressure, and extra bullets. The latecomer who stood over the single bed, doctor upon it, was experiencing Desoxyn (methamphetamine) withdrawal, was professionally under siege, and had recently been denied a seat next to the doctor at an upcoming tribute event. When she woke the sleeper, interrupting his high-priority slumber, he reacted with neither sympathy nor kindness. Seemingly, even in close proximity to a strung-out woman with gun, Herman Tarnower believed he remained in control of the situation, the personal dynamics of the room, the messy lovers’ triangle whose vengeful offshoots had already produced clothing smeared with excrement, slashed rugs, late-night anonymous phone calls, and serial face-to-face confrontations. His presumption proved wrong.

Jean Harris would claim that she had intended to kill herself that night, not Herman Tarnower. Suicide was her intention, her operational plan. Developments that complicated and disrupted her mission: an unwelcoming reception, a gun that jammed, a rival’s green negligee and pink hair curlers prominently displayed in the bathroom the headmistress considered her own. Later asked why, if she intended to kill herself rather than Tarnower, she hadn’t put gun to head at her Madeira School residence in McLean after “test firing” her weapon of choice into the trees from her terrace, Jean Harris said she wanted to avoid “future generations of Madeira girls” pointing out the spot “where the crazy headmistress killed herself.” Also, she wanted to say goodbye to “Hi.” Since at this point in their relationship, Hi (or “Hy” as others wrote it) couldn’t be relied on to take her phone calls, she would say goodbye in person, then shoot herself by the pond at the back of Tarnower’s property, site of many happy memories. That, Jean Harris insisted, was always her conscious intention. No, she had not planned for Tarnower to kill her. No, she had not fantasized that, shocked into recovering his romantic attachment, the doctor would beg her to spare herself harm, repledge his love and devotion and solemnly promise her the chair beside him at his tribute. The plan was to say adieu and die, alone, by the pond. And if this was indeed her plan, it was a plan that went spectacularly awry.

The Harris trial, held in White Plains at the Westchester County Courthouse, stretched over three months and ended with a conviction of second-degree murder and sentence of 15 years to life for the defendant, a ruling that held upon appeal. Serving time in the Bedford Hills Correctional Center, inmate #81G98 suffered two, possibly three, heart attacks, worked in the prison’s Parenting Center, taught sex education to former prostitutes and advocated prison reform via service on the Inmate Liaison Committee. She also wrote several books, the proceeds earmarked for a foundation that benefitted the children of inmates. In a publicity shot for her memoir, Stranger in Two Worlds (1986), she leans against a prison wall topped with curling barbed wire wearing pearls and a filmy blue tunic, hair held back from her face by the expected hairband. In December 1992, after turning down three previous petitions for clemency, New York’s then-Governor Mario Cuomo commuted Harris’s sentence. At that date, she had served almost 12 years of jail time. Prerelease, Harris objected to the clemency campaigns waged on her behalf in this fashion: “I don’t want to ask for clemency. I want to give clemency for what they did to me.” As a freed woman, Harris resided first with friends, then in a cabin in New Hampshire and finally in an assisted living facility in Connecticut where she died of natural causes, age 89, having outlived by more than 30 years the man she shot. The library of her alma mater, which houses, among other materials, drawings by Vanessa Bell and papers related to another well-known alumna, Sylvia Plath, is home to the Jean Struven Harris papers. According to the Smith catalogue, the collection contains correspondence, “writings,” memorabilia, news clippings, correctional systems research, legal documents, audio and video tapes and Harris’s “trial record.”

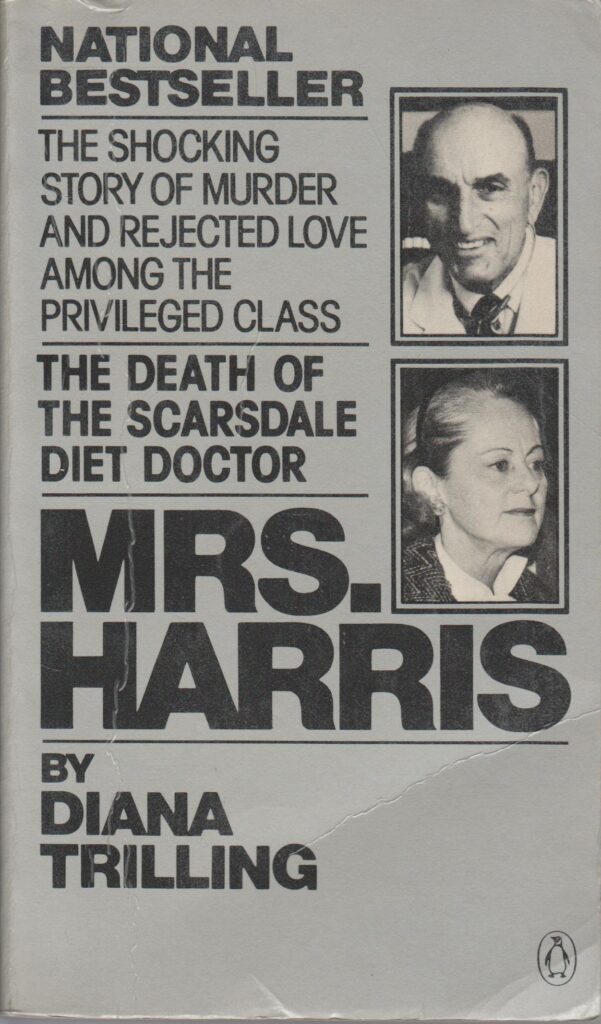

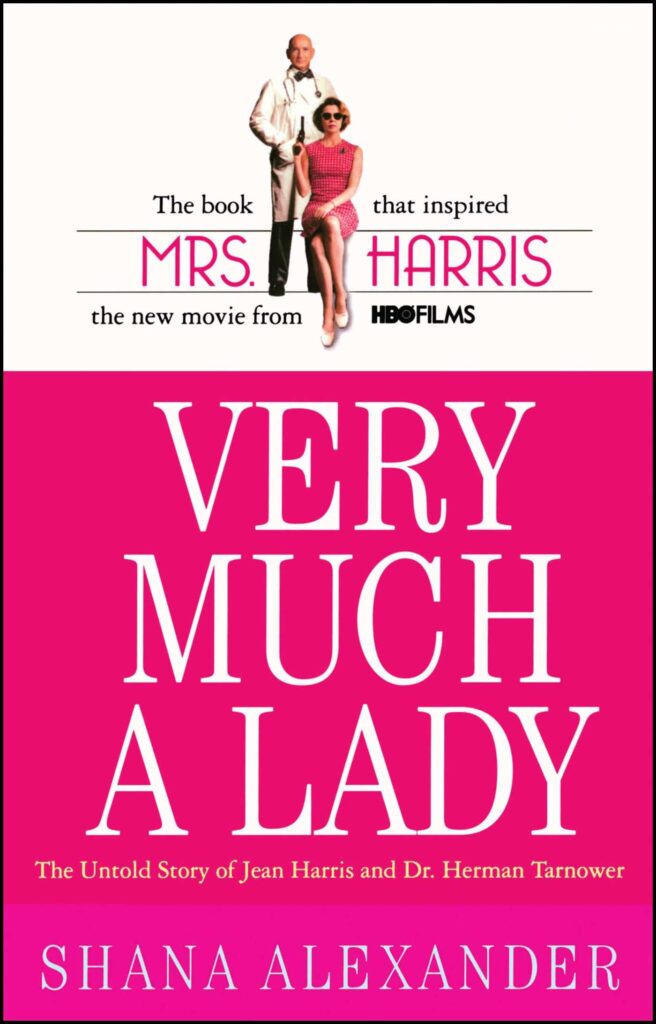

More than 100 writers and journalists showed up at Harris’s trial, the majority covering the event for daily newspapers. Reporting on the reporters in a New York Magazine article, Anthony Haden-Guest described “media luminary” Shana Alexander in “black mink” taking up the “Shana Alexander position” directly behind the defendant, the same post Alexander had occupied during the Patty Hearst trial. Both Alexander and critic Diana Trilling had committed to writing full-scale treatments of the woman accused, whatever the trial’s outcome. Those books, Trilling’s Mrs. Harris (1981) and Alexander’s Very Much a Lady (1983), published when the case remained relatively fresh in public memory, swiftly became bestsellers and forty years later retain their status as the definitive texts on Jean Harris. Comparing the two, Jonathan Yardley in The Washington Post kept it simple: Trilling’s book was “bad,” Alexander’s “good.” Another reviewer lamented that the books hadn’t been published in reverse order, Alexander’s researched account preceding Trilling’s meditative assessment. No reviewer suggested the authors took similar approaches in interpreting a headmistress at odds with herself.

In Mrs. Harris, Trilling is as much a presence on the page as the woman she observed for 64 days in court. Despite that authorial front-and-center, Trilling’s telling is cool, distanced. She admits that the Harris book is not her “usual line” of writing, but reminds readers “it had once been the high function of literature to deal with just such material, to acquaint us with our social variousness and our human complexity.” She had gone into the trial a Harris supporter, her stance “one of unqualified sympathy for the headmistress,” but along the way changed her mind. Critical to that shift in allegiance was evidence presented at the preliminary hearing but banned from the trial: Harris hadn’t arrived in Purchase with only a gun and a few extra bullets; she’d arrived with a back-up “box of ammunition” stashed in the glove compartment of her Chrysler that police discovered in an illegal search. Before being privy to the extra ammo disclosure, based solely on what she had read prior to the preliminary hearing and trial, Trilling had drafted a manuscript with the expectation of adding only a “summary” of the court proceedings. The draft, she soon realized, would require more than addition or revision; the whole of it had to be scrapped. “I could no longer think of Mrs. Harris as a symbol of our capacity for hurt and rage…. I had to acknowledge the possibility that along with the rest of the public I had been misled…even perhaps in my fundamental perception of her character.” The character of the woman seated at the defense table, once revealed, did not meet with Mrs. Trilling’s regard.

Alexander started partisan and remained partisan. “As is apparent,” she writes, “Jean Harris and I long ago became friends.” Alexander visited Harris in prison; they corresponded, letters that in 1991 were published as Marking Time: Letters from Jean Harris to Shana Alexander. In her Author’s Note, Alexander cops to an immediate identification with the accused: “She reminds me of me. Same hairdo, same shoes, even the same college class.” Beyond the lure of personal affinity, Alexander took up the project determined to right the wrong of previous “atrocious” press coverage and to show “readers what the jury never got to see.” Hers is a heated crusade for justice, a blistering indictment of the lover, defense lawyer and legal system that failed her friend. The tone of Very Much a Lady is frequently fierce, the chapter titles scathing. The chapter backgrounding Tarnower’s successful diet book is titled “Leibarzt Into Literary Lion.” Other chapters devoted to the doctor kick off: “Big Fish,” “The Greening of Dr. Lunch Hour.” A chapter on the Madeira school and Harris’s “punishing” schedule as headmistress bears the heading “Tender Little Ladies.” In contrast, Trilling dispenses with chapter divisions altogether, opting for the decorous break of white space.

In addition to interviewing Jean Harris formally and informally, Alexander, like the trained journalist she was, talked to “hundreds of people” who knew Harris and Tarnower: “old friends, new friends, professional colleagues, relatives, neighbors, servants, students, teachers, parents, doctors, lawyers, judges, police officers, and members of the District Attorney’s office.” Trilling’s position: “There’s a great deal that eludes one in Jean Harris’s early life…or perhaps because hers is a Middle Western story…it’s more elusive to my understanding.” Alexander, sharing neither Trilling’s misgivings nor sense of limitation, conducted an extensive investigation of Harris’s early life, delivering a plump account of Harris’s triumphs and setbacks, “good girl” behavior, scholastic achievements and life with father, “tyrant” and “bigot.” Trilling attempted to interview Alfred Knopf, Tarnower’s neighbor, and was “courteously” refused. Trying to negotiate her way into Tarnower’s home, she briefly exchanged words with gardener/chauffeur Henri van der Vreken, before Henri’s wife Suzanne, housekeeper/cook, appeared and Henri abruptly shut the door in Trilling’s face. Eventually Trilling spoke to a few students at the Madeira School, but she never interviewed Harris. Hunting down sources and double-checking data were not activities central to Trilling’s method of closing in on an interpretation. “The former Jean Struven was said to have been born in Cleveland,” she writes early on in Mrs. Harris, passing along secondhand information whose veracity, despite the archness of the phrasing, she apparently had no quarrel with.

More defining of Trilling’s style is a reliance on literary comparisons, literary asides. Among the many authors referenced: Agee, Eliot, Chekov, Flaubert, Fitzgerald, Tolstoy, Wharton. About the testimony of the fellow who’d slammed the door in her face, Trilling “doubts” that Henri van der Vreken was a man who’d been “reading Hamlet.” Freud makes several appearances. Presiding judge Russell Leggett “is no Freud or Trotsky but he has his own small gift of homely reference.” A witness for the defense has “a curiously Dickensian look” though Trilling is unable to “place the book or character.” Alexander, so moved, also calls up a literary analog. Describing Jean Harris’s two sons, she writes: “David Harris has Byronic chestnut hair”; “Jimmie Harris looks like Tom Sawyer in the Marine Corps.” Alexander’s other nod to high art versus no-nonsense reporting is the occasional—and startling—foray into atmospherics: “You could hear the horses snuffling down in the barns, and far away a groundskeeper clattered his mowing machine over billows of bluegrass lawn.” Neither Alexander nor Trilling references Dame Daphne du Maurier, but a Rebecca-ish take on the story is there for the snatching: Herman Tarnower’s household ruled by possessive Suzanne and Henri, determined by means devious or foul to keep their employer a bachelor, fending off all encroaching females in order to retain their own power and prestige within the hierarchy, Herman Tarnower, unlike Max de Winter, their eager accomplice because, as Jean Harris explained to Barbara Walters in an ABC televised interview: “It’s easier to get a woman than it is to get a cook, Barbara, let’s face it.”

“Moral” is a key word in Trilling’s lexicon. In an earlier collection of nonfiction, Claremont Essays, she puts the term to liberal use. In “The House of Mirth Revisited,” Trilling writes of Henry James’s “moral passion” and Edith Wharton’s “moral truth.” In “A Memorandum on the Hiss Case,” she defines “conscience” as “formulated moral intention.” In “The Oppenheimer Case: A Reading of the Testimony,” she writes: “Style is its own form of morality.” She devotes an entire essay to “The Moral Radicalism of Norman Mailer.” In Mrs. Harris, Trilling observes that Jean Harris, “in her connection with Tarnower,” had “let herself be led off her own moral path.” When Trilling appeared on William F. Buckley’s “Firing Line” to promote Mrs. Harris, her host cross-examined the author about what, precisely, she meant by “someone’s ‘moral style.’” “When I talk about moral style in my book, I’m not talking about transgressions,” Trilling replied. “I’m talking about choices in conduct. Everyone has a moral style.” Buckley pressed: “And your sympathy eroded in part because of the moral styles of the principals?” “Quite,” replied Trilling, “quite.”

In her book about Jean Harris, Alexander’s word of words appears in the title: “Lady.” (The entire title repurposes a comment Harris’s lawyer, Joel Aurnou, shouted at inquiring reporters: “Listen, fellas, you gotta understand my client! She’s very much a lady!”) Alexander homes in on both the behavioral dictates of the brand as well as its disastrous use as a defense strategy. Lizzie Borden’s lawyer, A.J. Jennings, used much the same defense to free his client from the charge of hacking to death first her stepmother and then her father in Fall River on a steamy day in August 1892. But stereotypes helpful to the cause in 19th-century Massachusetts faced a tougher sell in 20th-century Westchester County. Alexander situates Harris among the “well-bred little girls” of her generation “taught to become ‘ladies’ of a particular northeastern upper-class WASP variety.” (Harris grew up and attended high school in Ohio.) Being a lady required “ignoring or denying feelings that might ruffle the serene surface of life” and striving always to be “modestly understated, infinitely considerate of others…superbly controlled.” Professionally, Alexander admits, the “gracious, ladylike image” served Harris well when the Madeira board went looking for a new headmistress: “Jean Harris looked the part.” The image served Harris less well as an accused murderess. “None of Jean Harris’s lawyers understood her,” Alexander contends. “They knew she was a lady, but they had little awareness of what that entails.” For example, “Jean’s seeming lack of remorse”—which many onlookers, including Trilling, noted—“reflected her early training,” Alexander explains. “A lady does not show emotion in public.” On his TV program “Firing Line” when Buckley, playing devil’s advocate, argued the merits of “self-control” on the witness stand, Trilling responded: “If you’re arguing for self-command, it has to go across the board, doesn’t it?” Jean Harris “cried a lot in the courtroom, but she cried only for herself.” Ultimately, in Alexander’s opinion, being “too much a lady” was Harris’s undoing. The accused would “rather go to prison for murder [than] admit that she was jealous of the office girl,” Lynne Tryforus, Tarnower’s employee and younger lover. And go to prison Jean Harris did.

Trilling’s assessment of Harris is primarily based on the woman she observed in court; Alexander’s relationship with Harris carried over from the courtroom to the prison cell. Both report on Harris’s regrettable (in terms of acquittal) hauteur in court and arrogance on the witness stand, the defendant “queenly in her scorn” in Trilling’s phrase. Both authors also report on Harris’s flashes of temper, constantly jiggling foot, on and off dark glasses and “assistance” at the defense table, handing papers and photographs to her attorney as she deemed those materials pertinent. Of Harris’s appearance, Trilling writes: “As a well-bred victim, she’s from Central Casting.” Alexander goes in for wardrobe specifics, recording the head to toe components of Harris’s preliminary hearing ensemble: “tortoiseshell hair band, creamy tweeds, pale silk blouse, horn-rimmed half-glasses, sling pumps.” When Alexander studies Harris “in profile,” what she sees is a “lovely face,” someone who “looks no more than thirty. Her complexion is fine and transparent; a blue vein beats in her cheek.” Trilling’s “side face” view of Harris prompts a different conclusion: “To me her expression is that of the classic belle indifference of morbid hysteria, the corners of the mouth turned up in the fixed beginning of a smile.” Whereas Alexander laments Harris’s lack of “street smarts,” Trilling finds the defendant “naïve without innocence.” (For context: Trilling considered Marilyn Monroe the opposite: innocent, but not naïve.) Trilling is put off by Harris’s “very great…narcissism,” her abundant self-pity, her self-centeredness (“Shouldn’t her lawyer tell her that she ought at least to act as though she’s sorry Tarnower’s dead?”). Harris’s in-court composure as she traced “with her fingers the extent and distribution of the doctor’s blood” on the bed sheets appalled Trilling. “There’s not a glimmer of pain in her expression, no reluctance or distaste in her examination of the evidence. The bloodied sheets are but another datum in her self-defense.” Alexander maintains the headmistress is “fragile and high-minded”; Trilling pooh-poohs the fragile and disputes the high-minded: “Mrs. Harris strikes me as a woman of assertions far more than of courageous principle. In the clinches she opts for safety.” Regarding Harris’s mental health, Trilling concedes “it appeared obvious enough” that the defendant was “emotionally ill.” During a radio interview with Studs Terkel, Alexander offered a more specific diagnosis: Jean Harris, “classic depressive,” was a “woman in a state of psychosis” the day she wrote what came to be known as the Scarsdale Letter.

Written in red ink and delivered to the addressee’s home the day after he died, Harris’s letter to Tarnower, read in open court, did severe damage to her defense and went far in guaranteeing a guilty verdict. The ranting, pleading, accusing, self-justifying document bubbles with bile and rage and in its language and tone does not square with the “lady” claim. The letter writer, operating in what Alexander labels a psychotic state, pays forward the term, calling Lynne Tryforus a “psychotic whore.” It’s not a one-off attack. Tarnower’s “sick playmate” is a “lying slut” possessed of a “vomitous” voice, an “ignorant,” “tasteless” jewelry thief and excrement spreader who had “decided to sell her kids to the highest bidder.” Under the impression Tarnower had cut her and her sons out of his will in favor of Lynne and her children, Harris reminds Tarnower that while he has grown “rich” over the course of their relationship, she has, at times, been “almost destitute,” and twice had to borrow change from chauffeur/gardener Henri to pay the Garden State Parkway tolls. She beseeches the doctor to give her rival “all the money she wants…but give me time with you and the privilege of sharing with you April 19th”—the date of the tribute dinner. Both Trilling and Alexander reproduce the letter in full. In the defendant’s estimation, the main flaw of that outpouring was its “whiney” nature, explaining, on the witness stand, that her “role with Hi was…to be good company and not be a whiner.” Cross-examined by the prosecution, she testified that calling someone a “whore” was “very out of character,” then added the tone deaf afterthought: “But it’s not like me to rub up against people like Lynne Tryforus.” Updated on the art of trash talk in prison, the headmistress was advised by another someone she had not previously rubbed up against to “go fuck a dead doctor.”

The doctor who reportedly charmed scores of women during his lifetime did not charm two who wrote about him after his demise. In conveying their dislike of and distaste for the man, Diana Trilling and Shana Alexander pull no punches. “From the start of my interest in Mrs. Harris case, I didn’t like the Scarsdale diet doctor,” Trilling writes. “I didn’t like his face, his house, his book; and…as I learned about the musical chairs he played with women, I didn’t like his games.” Trilling thought Tarnower’s face “reptilian.” Assembled by “the era’s most successful packager of self-disgust,” The Complete Scarsdale Medical Diet was a “wretched performance,” the very definition of “vulgar snobbery,” Trilling told Buckley on “Firing Line.” Tarnower’s “was a meager soul, a spirit without generosity,” a man with “an insatiable appetite for small power.” Alexander’s bashing of the “aging, balding” man, his pretensions and sadism, gets more ink. “Autocratic,” a fellow interested in “dominion” and “control,” “arrogant,” “saturnine,” “bad-tempered,” “penurious,” a “snob,” a man who “twisted the ears” of his hunting dogs, who affected the accent of his Century Country Club cronies, who fancied himself a gourmet but always served, according to Alexander’s “food authority” source, “mush…swimming in gravy” in a dining room hung with big game trophies, an “unsophisticated lover” who “showed little refinement with women,” a doctor who prescribed extremely potent medications for Jean Harris not in the headmistress’s name. “This was malpractice. There’s no other word for it,” Alexander clarified, discussing Tarnower’s professional malfeasance on the Terkel broadcast. Trilling’s disapproval of all things Tarnower extends to his house, originally a pool house expanded into a residence of Tarnower’s design. “A small monument to cultural inflatedness,” Trilling writes, “a low two-storied house, not large but large enough to make a sizable bad impression…a Japanese—Japanoid—manifestation, a sort of domestic pagoda, the façade incoherent with terraces.” And those are just Trilling’s objections to the outside of the building. After Tarnower’s sister sells the property and Trilling is allowed an interior poke-about by the new owners, her opinion does not improve. “The inside is worse than I’d imagined,” she writes. The rooms are small, cramped, “deficient,” the whole house “claustral.” As for the site of the crime, “the doctor’s bedroom is a high-priced cell screaming for its walls to come down. I try to think what it would be like for a woman to be brought to this bedroom by a prosperous lover: if this is all the space he can buy with his money, what generosities of feeling should she count on?” Alexander, equally unimpressed with Tarnower’s home, pegs it “a curious glass-and-brick house in faux Frank Lloyd Wright style,” a “house that presented itself to the world in the grand manner but once inside the proportions were oddly foreshortened, like a stage set.” Alexander compares the constrictive kitchen to a “railroad dining car,” inventories the “slightly worn furnishings” of the downstairs rooms, the “mulch of giftwares” on display, many of them “monogrammed, embroidered, stitched” by girlfriends and grateful patients. The “so-called cathedral ceiling” in Tarnower’s bedroom Alexander judges to be low, stunted. As for bedroom furnishings, Alexander zeroes in on the “elaborately fretted and ugly work of massive cabinetry” that included “built-in headboards for two narrow, single beds,” the beds between which Harris insisted she and the doctor wrestled over her gun. Aesthetics aside, the spiral staircase that accessed the bedroom was impractical and, on the night of the shooting, a hindrance. Paramedics transporting the alive but dying doctor down its narrow twists and turns had a harder job than was strictly necessary. Herman Tarnower’s chosen staircase design wasted time the selector, in his final moments, did not have to spare.

Alexander devotes a chapter to the “travesties” of the case, discussing at length the errors of Harris’s legal team, including the “failure” to mount “a believable defense” and the go-for-broke strategy that preempted the “mercy” option of first-degree manslaughter. Harris’s lawyers, Alexander contends, should have argued extreme emotional disturbance because Harris’s was a “textbook example of an EED case.” On this point, Alexander had many backers, including the presiding judge. To argue “innocence”—or accident—in the face of four spent bullets is a problematic undertaking. Jean Harris considered herself innocent of the crime with which she had been charged. She did not want to be tried for manslaughter because she believed it amounted to a plea bargain and only the guilty opted for a plea bargain. She forbade her lawyers to criticize Herman Tarnower or Madeira. She did not want any psychiatric testimony introduced. Harris’s lawyers should have overruled their client’s wishes, Alexander insists. But they didn’t; they obeyed the headmistress. James Harris, speaking to Barbara Walters, described Aurnou as “underpowered,” lacking the “strength…to tell mother what to do.” During the trial, Harris herself seemed pleased enough with her counsel, telling reporters that Aurnou was a “genius,” optimistically predicting “he may get me off.” As an inmate, she would revise that good opinion and complain to NBC’s Jane Pauley (and others) that she’d been given “bad legal advice.”

Trilling’s quarrel with the verdict focuses on the prosecution. Although she “sees no travesty of justice in the jury’s decision,” she believes the prosecution failed to prove beyond reasonable doubt its case for murder in the second degree—the conscious intent to kill. Despite “questioning the verdict,” Trilling harbors “no doubt at all that deep in her mind and heart (Harris) wanted to kill Dr. Tarnower. I think her fury at him was murderous and that this was plainly and repeatedly revealed.” However: “If there’d ever been a time when the wish (to kill) was conscious, this was no longer so. It had departed her conscious mind, gone…where consciousness doesn’t follow.”

In 1981, the same year Trilling published Mrs. Harris, NBC broadcast the TV movie The People vs. Jean Harris, starring Ellen Burstyn, a Harris supporter and contributor to the Jean Harris Defense Committee. The TV movie’s scope is the trial and trial only, the drab, minimalist set a paean to the color tan. It’s an earnest effort all around. No character in the cast comes off tightly coiled. Burstyn’s muted, flattened performance gives no quarter to fury or prickliness and transmits little of Harris’s widely reported snootiness. The actress plays the accused as a woman weighted with grief (as opposed to guilt), soft-spoken, hesitant, occasionally confused and largely compliant. Because the principals—prosecutor George Bolen (Peter Coyote), defense attorney Joel Aurnou (Martin Balsam), judge Russell Leggett (Richard Dysart), witness Suzanne van der Vreken (Sarah Marshall)—along with scattered members of the jury wear oversized eyewear, Burstyn/Harris’s oversized sunglasses seem little more than prop, and a common one at that.

HBO’s 2005 production is an altogether brighter, splashier, campier enterprise, filmed in multiple locations. Borrowing its title from Trilling but citing Alexander’s book as its inspiration, Mrs. Harris, the movie, stars Annette Bening and Ben Kingsley, covers the Harris/Tarnower affair start to finish, and isn’t afraid of humor. Bening gives her Harris a knowing, worldly, sarcastic edge. A single anonymous quote in Alexander’s book on the topic of what women “saw” in Tarnower (“You never got into the locker room at Century, or you would know what they see”) gets its own scene, a towel-less Kingsley strutting and strutting and strutting his equipment down the locker room aisle, basking in the admiring stares of his fellow country clubbers. Even the wrestling for the gun between a zombie-ish Bening and irked Kingsley verges on the comedic. An awkward, clumsy tangle of limbs in the too-small space between beds, a loopy Bening on her hands and knees searching for the dropped gun, the actress’s slightly ironic delivery of the “phone’s dead” line. Rather than a Harris desperate to achieve one last chat with her lover, Bening’s rendition conveys a quizzical befuddlement at finding herself in the Purchase bedroom, now and again gazing upon Kingsley’s Tarnower as if upon a puzzling illusion, a man in pajamas who should be her beloved but whose impersonation in the moment doesn’t quite convince. Nowhere to be seen during the trial, Lynne Tryforus lacks cinematic representation in the first film but in the second puts in a leggy appearance via Chloë Sevigny. It’s a small role—too small for Chloë Sevigny fans. Given the screen time, Sevigny might have succeeded in bringing the most mysterious member of the romantic triangle into better focus.

In Alexander’s opinion, the Jean Harris story “rises to the level of tragedy” because Jean Harris’s “character—her mix of unsparing honesty, idealism, integrity, and ‘lady-like’ values—became caught up in forces beyond her control.” Trilling grants that the shooting was a “tragic happening in the headmistress’s life” but stops short of granting the overall saga the tragedy stamp of approval. Very likely that withholding stemmed in part from what Trilling perceives as a “suggestion of sordidness” in Tarnower’s household—people “informing” on each other, stealing money, slashing and befouling garments and furnishings—and Jean Harris’s active participation in the ongoing intrigue. Trilling viewed the Harris/Tarnower imbroglio through the lens of class: “The only thing that distinguished the Harris-Tarnower story from usual crimes of passion was its social location and the repute of its leading characters.”

Tucked into the pages of each book, Trilling’s and Alexander’s, is a showstopper sentence. From Trilling: “I still saw (Harris) as a woman who thought she loved a man whom she deeply hated—it’s not an unfamiliar phenomenon.” From Alexander, disputing the claim that Harris, in putting up with Tarnower’s treatment for 14 years, qualified as a “terrible masochist”: “Every woman in love tolerates pain she would not otherwise tolerate. That is the nature of love.”

Held by interpreters of the Harris/Tarnower misalliance, those beliefs are not without significance. Two clear-eyed skeptics of love, the fairytale, took as their subject self-deceiving Jean Harris, fool for love. Of the two, only one remained her subject’s champion.

Kat Meads is the author of 2:12 a.m., essays inspired by insomnia, a Forewords Review Book of the Year finalist and the recipient of an IPPY Gold Medal. In addition to Full Stop (“Charming (to Some) Estelle”), her essays have appeared/are forthcoming in New England Review, Eclectica, the Southern Review, Crazyhorse and Agni online. She lives in California.

This post may contain affiliate links.