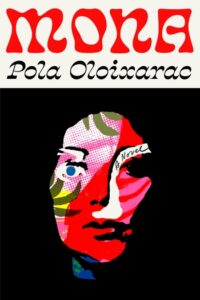

[FSG; 2021]

Tr. from the Spanish by Adam Morris

It is a well-rehearsed cliché that the pursuit of knowledge and the experience and creation of art make us more whole. But what does it mean to become more whole? Zadie Smith scoffed at the notion that there was any one register to being human in her response to James Wood’s critique of the “hysterical realism” of White Teeth (which, he argued, “knows a thousand things but does not know a single human being.”) “Be more human?” she asked rhetorically. “I sit in front of my white screen and I’m not sure what to do with that one.” Satire, irony, and caricature, Smith argued, are no less human than tragedy or deep sentiment. Demanding more humanity from ourselves and others, it seems then, is a troubled and ill-defined project. Still, even conscientious skeptics of the premise of the humanizing process — me included! — pick up books, watch films, and attend lectures with some inkling that these activities make us better.

The title character of Pola Oloixarac’s Mona, translated from Spanish by Adam Morris, is a Ph.D. student at Stanford and published writer. Mona’s breakout work has landed her a nomination for a prestigious literary prize, and she shuttles herself off to a picturesque Swedish village to consort with fellow nominees for a weeklong gathering. Mona’s life, readers quickly find, is a refutation of the thesis that academic and literary enterprises are naturally given to the cultivation of wholeness. Mona’s traumatic recent past can be gleaned through italicized inner dialogue and persistent text messages, all of which she clinically evades even as they threaten to disturb her aloof professional persona. She maintains several social media profiles through which she “trolls,” each with its own curated identity. She vapes constantly, drinks heavily, and pops pills to quell her nerves, and these habits aid her in keeping her multiple personalities separate.

Moreover, Mona’s invitations to the exclusive milieus of Stanford and the literary festival are predicated on her self-conscious performance of Peruvian identity. She analogizes her experience at the modern university to that of a caged zoo animal; she takes perverse delight in thinking of herself as an endangered specimen. And in Sweden, she is well aware of the bountiful rewards that come with representing national flavor in international contexts. She apathetically watches a succession of writers lecture on topics that cohere with what is expected given their national identities. An Iranian writer denounces the repression of women in Iran; an Israeli writer ties every discussion to the Holocaust; a French writer parrots an existential passage from Beckett’s Malone Dies. She follows suit, delivering her own lecture on Amazonian culture. Yet this endless cultural display of authenticity ends up feeling not very authentic at all. As Jorge Luis Borges once wrote in response to critics who complained his work was not Argentinian enough, “in the Arab book par excellence, the Koran, there are no camels. [Mohammed] knew he could be an Arab without camels.”

The picture of Mona that emerges is one of a woman whose reigning trait is her dexterity in managing multiple selves. She exhibits none of the organic holism vaunted by Aristotelianism or gestalt theory — a holism often uniquely expected from women, who tend to get diagnosed with hysteria whenever their lives contain contradictions. The archetypal hysteric is the woman who has lost grasp of reality, unable to function in her social contexts as she gradually unravels. But Mona’s command of several personalities, to the contrary, is a masterful act of manipulating her self-presentation to fit the twisted logic of the contemporary academic space and the global literary scene. Mona’s habitual dissociation is not a breakdown on the steps of these ordered systems and institutions, but rather an embodied and psychological effect of being their poster child. The constant work of compartmentalizing and presiding over her various identities might explain why she finds so much pleasure in losing consciousness, whether it is drifting off to sleep or getting drunk and high.

Just as Mona is enjoying one of these moments, showering herself in water so cold she is close to passing out, a woman called Lena disturbs her peace. Mona and Lena once crossed paths in Lyon at another literary festival, and Lena is insistent on discussing a question Mona had posed there. Do they lead their lives for themselves, or do they instead live for “the monster who writes”? Mona is minimally engaged, but Lena pushes on. She proposes that writing has to be done in drag. What’s more, she says, writing is trans. “When I say we play the part, what I mean is that we live it,” Lena says, impassioned. “We’re forced to go beyond our minds — we’re obliged to incarnate these personae. And there’s nothing as womanly as incarnation.” Lena’s polemic is well-argued, but it veers on the uninvited and personal when she assails Mona’s physical appearance and makeup to make her argument. Lena has hit a nerve, and Mona scampers into the woods when Lena is distracted.

Each conversation and lecture Mona participates in promises to offer new angles on (to regurgitate a favored phrase at these kinds of events) the defining questions of our time. But like many real academic conferences, the literary prize festival proves to be a of hall of mirrors. The reader’s suspicion that the whole event is an elaborate sham builds as it progresses through each day. A fellow Latin American writer serves up predictable references to the tumultuous political events of his childhood. A dainty, coiffed Japanese poet carries a quality of ethereality that borders on unreality. Is the prize festival a grotesque historical reenactment of the present from a future standpoint that Mona has not been clued in on? The writers’ roles seem predetermined, their characters petty. At the festival bar, Mona blurts out, “The festivals are the real novels!” Festivals turn writers into characters, Mona explains. Writers arrive as the creator of possibilities and worlds, but they depart as puppets, functionaries for a plot. Or worse, as flora and fauna for the landscape.

If the gathering is full of pretenses, is something being covered up? And which writer will be the crowned the winner of the esteemed Basske-Wortz Prize? These simmering questions inject a world-weary and conspiratorial air to the whole affair. A cohort of Nordic blonde men mysteriously appear and disappear; a fox with a violently slit throat turns up. Is there a dark underbelly to the festival that Mona is discovering traces and shards of? I felt a vestige of Mona’s nervous state throughout the novel, defensive and mistrustful, ready for the conference to be upended at any moment. It might have had something to do with the genre indeterminacy of Oloixarac’s writing, which persistently kept me on edge. Mona could be labeled a satire of the contemporary world literature circuit, but that description would miss the psychological unease that undergirds every academic exchange. Its conclusion could be called absurdist, but everything that precedes it is eminently sensible. Oloixarac seems intent on locating a style that defies the conformism her characters succumb to.

In Mona’s case, the “identitarian fantasy” she performs catapults her into literary stardom. She is praised for her vitality, for her assumption of the mantle of “heiress to the Boom.” But all this plasters over a rudimental death drive, which Oloixarac conveys lyrically and calmly rather than violently. Mona, for instance, does not wish for the obliteration of her own consciousness — that kind of self-destructive impulse would be too direct for Oloixaroc’s taste. Instead, Mona relishes in inducing the feeling that her thoughts are like “an archipelago welcoming the rising seas.” Writing, Mona implies to a lover at the festival, grants her momentary freedom from the simultaneous drives of thanatos and eros. What she wants most of all, she whispers, is to access her unconscious.

Art and intellectual inquiry need not be circumscribed to the mandate of making our lives more whole. We should not allow academic institutions, conferences, and literary prizes to demand ever more exotic identities from us which force us to ritually forget our other selves in the name of wholeness. On the other hand, is entertaining multiple personalities in a permanently distressed state the fate of the woman writer? These are important concerns that Mona cannot fully address, detached as she is throughout the novel. The basic premise of her identity-based research is not that her personal experiences should inform her work, but instead, that identity — that unity in multiplicity — is obscured, perpetually out of view. Little, in fact, is known about her prize-nominated novel. While Mona is a convincing representative of the discordant life of an Internet-age, post-Donald Trump, young “person of color” in the academy, I was left desperately trying to resist my temptation to ask for more. Who is Mona and where do her investments lie?

I remembered that Zadie Smith essay again, when Smith imagines Wood prodding her to tell us how it feels. “Well, we are trying. I am trying,” she insists, exasperated. Mona occupies that same space of tension, striving for sentiment and feeling while portraying the fragmentary texture of contemporary life. A series of utterly unforeseeable events transpire in the final pages of Mona, written with a nod to mythic and magical realist tropes. It is only fitting, I suppose, for an ancient Nordic legend to plot its own revenge on the flattened space and time of the global festival. In that scene, the fight between Mona’s writerly desire to plumb her own subterranean psyche and her desire for freedom is settled in favor of oblivion. The threat is that she will not emerge more whole, but that she will instead be swallowed whole, buried under the accumulated debris of her many personas.

Jasmine Liu is a writer and journalist from the San Francisco Bay Area. Currently, she likes thinking about books, contemporary art, and classical music.

This post may contain affiliate links.