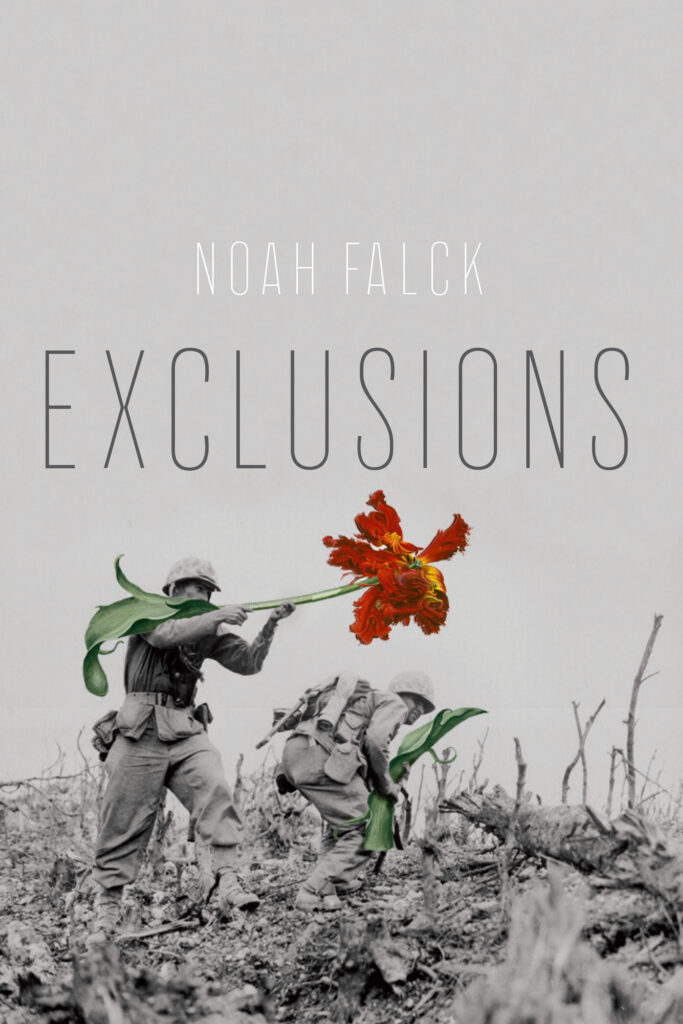

I read Noah Falck’s poetry collection Exclusions fairly quickly, but that’s not because it’s an insignificant book—the opposite, actually. Comprised of 55 compact poems, one poem to a page, Exclusions is short for a contemporary poetry volume, but therein lies its appeal as well. These are poems that have been pared to the proverbial bone, excluding (yep) everything except the sheer necessity of the thing. (And what that necessary “thing” is changes from poem to poem; the brevity of the book paradoxically expands its multitudinousness.) Below I asked Falck about the central premise of Exclusions, Zoom vs. in-person readings, and his hopes (literary and otherwise) for the future.

Jeff Alessandrelli: I’m curious how the conceit of Exclusions came about. The poems are enacted via what isn’t there — “Poem Excluding the Metric System,” “Poem Excluding Religion,” etc. I was somewhat reminded of the lines “In a field/I am the absence/of field…Wherever I am/I am what is missing” from Mark Strand’s well-known poem “Keeping Things Whole.” Did the premise of the book come hard-earned or was it one you simply sat down and started writing within?

Noah Falck: Oh man, I love that Strand poem. And so much of Strand’s work. I think I was first interested in writing poems that held everything inside them. How do you write a poem that contains all of the world and more inside a sonnet length piece? So I sat down and failed every time I composed such a poem. Then the reverse was exercised, let’s try to write a poem that works on leaving a single thing out. These also seemed to fail, but in ways that felt more true.

Once the idea and form presented itself and felt real, I began thinking about what would be interesting to leave out. I carried around a pocket notebook to catalogue the every day. What did I notice on the bike ride to work? What was the sky doing when those kids broke into a fist fight in the parking lot? What’s a poem that leaves out taxes? Leaves out the metric system? That sort of thing. I generated a list of what to exclude and then wrote those poems.

Exclusions seems like a poetry collection that’s out of time, in that it doesn’t directly speak to any current events or movements. None of these poems are identity-based and there’s an emphasis on the imaginative throughout, with surreal similes and metaphors (often suburbanly so) abounding. Was that a conscious feature of the book or simply who you are as a poet?

I’ve always thought of poems as imaginative acts, or at least a space where the imagination can be let off the leash to run wild. I’ve always been drawn to books that present wonder and weirdness side by side. Is that a sort of equation for inviting the imagination in — wonder + weirdness? Maybe. Maybe not. But it helps me register and engage. It opens up the lane for certain images to arrive, for certain collisions to potentially happen. It brings to mind Matthea Harvey’s Sad Little Breathing Machine, Charles Simic’s The World Doesn’t End, and Mathias Svalina’s Deconstruction Myths. All these books, I think in some way, use that sort of equation. And they’ve all had a major impact on me and my thinking about what poems can do, and how imagination can propel you forward.

POEM EXCLUDING OPPOSITE DAY

Every thought you have becomes

the future

tattoos of sad children

in federally

funded afterschool

programs. The

river gets a life

and then burns.

People wait

in line to give

blood, to devour

the future.

Bird songs carve

through the air

until sunset.

It’s always

December

in the next

chapter of your life,

your thoughts

slowly replaced

by freezing

rain.

Gestation is another thing I thought about while reading Exclusions. The book is comprised of 55 poems, 1 poem a page. Most of the poems are shortish, with “Poem Excluding Rust” being a single line. Your last full-length poetry collection came out in 2012; Exclusions appeared in 2020. I assume some of the time between collections was spent on writing and finding a worthwhile publisher, but during that 8-year-gap between published books were you writing different things or putting together different versions of Exclusions? Or? And as you’ve grown older, has the writing grown more important than the publishing of said writing? (For that latter question, that’s just the case with me—so maybe I’m projecting my own feelings onto you.) Vis-a-vis the time you spent working on it, what does success look like for you with regards to Exclusions?

I do like to gestate on my poems. But I’m not sure I’m down with the word gestate — it makes me think of prostate which makes me think of my grandfather and the clean, cold floors of hospital rooms. Typically, I try to write a skeletal version of a poem and let it sit for a month or two. Then return to it and add some of the muscle. Leave it alone again and continue building it for a while sort of like an airplane, until I think it can fly. Though like most homemade airplanes they often end in some sort of crash.

The exclusionpoems were written over the course of 3-4 years, but a chunk of the book was written rather quickly, at least the first drafts. I tinkered with them for several years and sent it out to publishers during the tinkering phase. I still continue to tinker with some of the poems in the book. Tupelo selected Exclusions during their open reading period in 2017 and it went through some small revisions the following year, and then was put in line to be published a few years after that. It didn’t actually come into the world until August 2020. I guess that’s a typical publishing timeline.

In those 8 years between books, we moved to Buffalo from Dayton, Ohio. I started a new job at Just Buffalo Literary Center. I wrote a chapbook, You Are In Nearly Every Future, that came out in 2017. I started a reading series in an abandoned grain silo and my wife gave birth to a child. A whole other life seemed to happen between books, and I feel good about that. I like the idea that each book you write is a wildly different you. Hopefully a more aware and gracious you.

I think the process of writing is more important than the recognition of a publication. I love the actual act of sitting down and struggling over the sound and architecture of a piece. How can I put this thing together — this image, that emotion, a part of a memory. Will it work? Do I even know how to do this anymore? More recently I’ve been returning to what I think helped me start writing poems in the first place — the freedom to explore, without worry, and to write what I may not recognize as a poem and be not only okay with it, but happy.

I still feel good about so many of the Exclusions. I still find a certain joy in reading them out loud to friends on Zoom across the country. I guess that’s a sort of success — finding joy in something you made so many years ago.

I guess your final paragraph to that last question brings me to my next one—what was the process like in terms of the book being published during the pandemic and how did that impact things for you? It’s obviously out of your control and involves circumstances much bigger than a new poetry collection, but were you disappointed that you didn’t get the chance to go out and do more physical readings, meet more folks IRL, etc.? Or have the Zoom readings sufficed? There’s been a lot of talk about things going back to “normal” once Covid 19 vaccinations happen and we curtail our screen lives (at least a bit), but at the same time I’ve also heard from different folks that online readings are, across the board, way easier for everyone—more people show up, they’re easier to set up, accessibility and venue concerns aren’t an issue. But as someone who used to run a reading series and grew up doing a lot of readings, sometimes driving for hours to read to 12 or 14 people…I don’t know. Zoom readings just seems like a completely different thing, comparatively. Do you have thoughts?

The book being published during the pandemic, to me, was really unfortunate. I’m all for celebrating such events. I couldn’t hug my friends or spill drinks on them or any of those in person things that make life worth living. I tried to make the most of it. In August of 2020, when the book was “released,” I put together some in person, socially distant sidewalk, porch, and/or garage readings for people in Buffalo. Small readings of no more than 4 people at a time. The opportunity was also extended to anyone who wanted a short Zoom reading of a few poems. It turned out that I was mostly reading poems to friends both on their porches and on Zoom in different time zones. There were a handful of strangers who were interested and those readings were so wonderful, and moving in ways I didn’t imagine they would be. There was one where I was reading to a nurse in her driveway and when I read “Poem Excluding Air Quotes,” she began sobbing loudly. I finished the reading, but was more interested in giving her a hug.

Zoom readings seem to feel like a necessity right now, but they don’t replace people actually coming together for a collective experience in a shared environment. They never will in my opinion. I love the accessibility of being able to see Yusef Komunyakaa read on a Wednesday and then Terrance Hayes and Claudia Rankine in conversation on a Thursday while I’m simultaneously watching my Dayton Flyers basketball team on mute on my phone, but I think that’s the problem. And I don’t think it’s just me either. If I was actually at a Komunyakaa reading or a Hayes/Rankine event, I wouldn’t be folding clothes or cleaning the fish tank or telling my kid not to run through the living room with scissors, I’d be fully present in the space engaging in that collective act of listening, you know? It’s a special thing that can’t be achieved inside a Zoom webinar or classroom or whatever. I’m looking forward to when we can come together again as a community, both strangers and friends, and smile and cry and fidget and think and afterwards discuss it all in a bar or parking lot or field or inside a grain silo. I’m looking forward to whatever version of those are ahead of us.

Touching on your notion that poem are “imaginative acts” I was curious about your relationship to words like “earnestness” and “irony.” Exclusions seems like an exceptionally earnest book, complete with heartfelt and surprising images, similes and rhetorical statements. At the same time, it’s a collection that playing with the nature of earnestness. There’s a campiness to lines like “I like to/ confess the rarest of dance moves/ in total drunkenness,” from “Poem Excluding Corporations” or “We are flying over the heartland, and/ the sky waits for God,” from “Poem Excluding Elegy,” but behind the poetry is a clear-cut sincerity, one the reader is led to believe is capital t True. I remember 15 years ago there was a group of poets calling themselves members of the New Sincerity school and that always struck me as slightly odd—aren’t all poets sincere in one way or another, especially the ones that couch said sincerity in something else besides potentially bald or didactic literalism? With regards to both your own poems and the wider framework I mention, do you have a take?

People are going to label and categorize poems or associate them with certain “schools” of thought, but I don’t think about it all that much, particularly when I’m in the act of writing. I mean writing for me is a way to interrogate my own wonders, to consider the things in my life, in my mind that keep sparking different curiosities and figuring out how to translate those wonders onto the page. Sometimes those translations, those lines, show up in the form of humor or irony or sincerity. I think this happens because I try to let as much of the world into my poems as possible.

In terms of the larger question about the wider framework and the New Sincerity, I don’t know. I think it’s kind of fun to think about assembling a school of thought, though I know it wasn’t actually assembled. Mine would be the School of Attics & Basements, as much of my work is considered in those spaces. The bottom and the top. But seriously, writing can be such a lonely journey, if you are connecting with other writers and artists who share similar sentiments, then cool, build that community out, make things that you think are going to change the world, ideally for the better. I don’t have much to say about reclaiming a state of being. I mean is it revolutionary to care or to express care inside a poem? I certainly hope not. But someone will critique it nonetheless.

POEM EXCLUDING FUTURE

Now the snow is

black and we feel

dirty in its

presence. Cigarette butts

blow across the

wet pavement like

children

leaving school during a bomb

threat. There’s

a good chance we have

no chance is

what your thoughts are

during your

daily commute to the

office. Roads

break apart as variations

of sadness. And

now the sky is all

truffles and

shoe polish. It rehearses

the end over a

cemetery full of

children

trapped in moonlight.

I love the idea of a School of Attics & Basements and fully agree that all School-based thought is largely a marketing tool, a critical-convenience based thing. But I’m curious about those writers and artists who you do share kinship with—who are they and why have you gravitated to their work? I guess I’m thinking contemporary folks here, but certainly deceased ones too.

I think I’ve always been drawn to those who don’t follow the rules, those who appear to invent new ways of looking, and those who use language as vehicles to harness the strange and the wild. All the folks who were kind enough to blurb Exclusions fit into those categories — Natalie Shapero, Zach Savich, Graham Foust, and Michael McGriff. I have such great admiration for all of them and their work. I would also add Leslie Lewis, Richie Hofmann, Mary Ruefle, Marcus Jackson, C Dylan Bassett, and Eric Baus to this list — as poets who welcome a difficult kind of playfulness and at the same time, a great sense of care into their work. There are really so many more I feel close to and it is changing all the time, as is this thing we call poetry.

Oh, and maybe I would mention Dayton singer-songwriter Robert Pollard of Guided By Voices. But I think the kinship with him is that we both come from Dayton, Ohio, and that he was one of the first artists I knew who was able to write about home in ways that felt otherworldly. And though he is often pinned as reckless and someone who drinks too much — I respect his drive and his discipline to his craft and how it appears that there is a chip forever on his shoulder.

How important is social media in terms of your poetic practice? I don’t mean in the writing of the poems, but in the disseminating of them. Is spreading the word about a poem that you wrote and published just as important as writing it? Not even close? Or…?

I think social media can be a wonderful way to share your work with the world (if the world cares to listen), but I personally am in no way, whatsoever, writing poems so I can then share them on the internet. So, no, it’s not part of my practice.

I am on social media (mostly Twitter & Instagram) and I will share my poems or poetry news and I will retweet poems that excite me. My feed contains mostly poems or poets walking dogs or cats dressed up like people. I do enjoy the fact that I can open Twitter and read poems of all different styles from all different sorts of publications from a range of poets of all walks of life. It’s like getting a poem-a-day, but instead you’re getting fifty poems-a-day from fifty different editors/curators. There’s a joy in that diversity.

Finally, what’s next? Are you writing more poems, building towards a new collection? Writing different stuff in other forms? Or? Where do you hope to be with your life and work by this time next year?

I am writing poems, but I’m trying not to force anything into the world. There’s no reason for it. I’m trying to slow down, which feels like swimming against a bursting current. I’m trying to find more joy in the day to day. Read more novels, drink more water, listen to records all the way through.

Time has held a different rhythm this past year (clearly), and thus has made it hard for me to consider the future, even the near future. But I would say I hope to just continue to be afforded the time and space to write. It’s become more of a meditative practice than I could have known, and I’ve been so grateful to be able to dive into that space with some regularity, particularly during the pandemic.

Maybe next year I will print off all the poems I’ve been writing and send them to someone who will want to bind them into a book. Maybe I will be able to return to the basketball court and truly learn the appropriate range of my jump shot. Maybe my kid will have her first sleepover. But I hope most of all that I can safely sit down with friends and listen to their poems in person. I hope we can talk deep into the night and appreciate the time we share together as it is a most precious thing. Now that’s not new, but some real sincerity.

Recent work by Jeff Alessandrelli appears or is forthcoming in BOMB, Poetry London, Denver Quarterly and the Hong Kong Review of Books. Called “an example of radical humility…its poems enact a quiet persistent empathy in the world of creative writing” by The Kenyon Review, Alessandrelli is most recently the author of the poetry collection Fur Not Light (2019), which the UK press Broken Sleep is going to release a version of in June 2021.

In addition to his writing work Alessandrelli also directs the non-profit record label/press Fonograf Ed.

Noah Falck is the author of the poetry collections Exclusions, You Are In Nearly Every Future, and Snowmen Losing Weight. His poems have appeared in Poetry Daily, Kenyon Review, Literary Hub, and Poets.org. In 2013, Falck started the Silo City Reading Series, a multimedia event series featuring live music, art, & poetry inside a 130-foot high, abandoned grain elevator. He lives on Buffalo’s West Side with his wife and daughter.

This post may contain affiliate links.