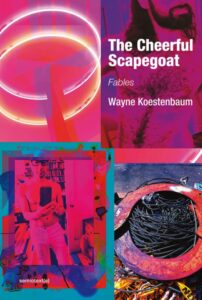

[Semiotext(e); 2021]

1. Beyond the boundaries of expression

A typical, if anything can be called typical, fable in Wayne Koestenbaum’s new collection, The Cheerful Scapegoat: Fables is both cerebral and playful, abject and perversely spiritual, funny and serious; which is to say, it is an anarchic text, where intense desire electrifies the language on the page. It’s also a writing in drag, that performs a subversive and scandalous striptease, collapsing the authority of the King’s English; it plays with many masks, wears many costumes, is theatrical, amoral. Sarah Chant writes, in “The Plurality and Quasi-Anarchism of Drag,” “Drag reinvents the experience of everyday life. Carol Ehrlich notes in Anarchism, Feminism and Situationism (Black Rose, 1977) that this is done by ‘creating situations that disrupt what seems to be the natural order of things.’” Furthermore, Chant writes, “What fascinates me about drag is precisely this: it opens up the possibilities for mind-body experience, creating a space and opportunity to go beyond the boundaries of expression.” Koestenbaum’s is a language that accomplishes both of these things: disrupting hierarchies and leaving a taste on your lips. It is a strange and wonderful elixir.

2. A Pessoan gesture

Identity is fluid in Koestenbaum’s prose; the narrative voice is constantly shifting; the “I” sometimes takes the form of an omniscient narrator, sometimes a character in the story, and sometimes it leaps out of the page to talk directly to the reader. In response to a question, in “Conversation in Darkness,” about whether there is a “non-sexy omniscience,” the narrator responds: “No, it’s always sexy to know, always sexy to spy, always sexy to partake of someone else’s consciousness, especially if that person thinks her consciousness is ringed round by impenetrable forces.” The “I” is split and porous. The writing is a Pessoan gesture, where multiplicity rather than unity, fluidity rather than rigidity, transsexuality instead of heterosexuality or homosexuality, become the strategic means of re-ordering thought to bring about a revolution that overthrows the established norms concerning gesture, language, and the body.

3. Pockets of Refinement

Koestenbaum is playing hide and seek in the language; in “Conversation in Darkness” the narrator engages in a dialogue or perhaps a monologue:

Is my porousness an essential part of what you love?

What I love most about you is your near-invisibility.

And were I fully to materialize, you’d grow disenchanted?

In the political/legal/medical system as it is constituted, if one wants to live, one has to adopt and accept its codes; the medical and legal systems cannot accept the unknown, what deviates from their conception of the truth, and what is always partially visible in the language. The “I” must be the authority figure; but the narrator in “Gauffrage and the Erotic Limitations of Capability Klein” has a “bad odor. The smell around me is thick, like a gelatinous soup made worse by cornstarch. But within my bad odor there exists pockets of refinement and oasis, where you could rest between scenes, while you wait for your plunge into mal-olfactory, or Maillol Factory, Mal Oeil Factory, or Oiled Male Factory. Mere wordplay!” Authority or power is deflated; the “I” is a stain on the language, a cum stain perhaps?

3. Without a specific destination

What is transitional, borderless, migrant, not clearly defined in terms of sexuality, anatomy and language, must be codified, documented, made recognizable, reproducible, predictable, linguistically consistent; that produces a good moral citizen: one who is moral and whose sexuality is not ambiguous. But Koestenbaum is not a moralist. In “The Gardener’s Scarf,” the narrator writes, “I speak on your behalf because I am a Sally, a male Sally, or a transmuting Sally without a specific destination on the gender spectrum.” Koestenbaum’s prose is not one with distinct edges; it is porous; the agency of the I is ceded, “meanwhile polishing the silver slipcase of your own inner tabernacle.” The King’s English would rather demand “constant verification” lest the precious tea room, sight of petite-bourgeoisie pleasures in the 19th century, “slide into decrepitude that rubbed against its noble reputation, as two notes in a minor second rub against each other to create havoc.”

4. Above or Below

The narrator in “The Gardener’s Scarf” continues: “Only a perfectly logical and morally sound transport between sleep and death could allay the anxieties of a tea room inspector nervous about job stability and about his own place in a cosmology spinning out of a benign deity’s control.” In this sentence, Koestenbaum hints at spiritual concerns: the benign deity has no control. What is man’s place in this cosmology? The narrator says: “I’ve acquired a festering disease, lying here in a field of heather . . . Radical indecision, unvisualizable and finite: am I in a blooming meadow, or am I in a basement?” Above or below? Paradiso or Inferno? It is “Unvisualizable and finite” because the narrator cannot see into a Beyond and thus our knowledge is finite, limited, as we are ourselves. Furthermore, he writes in “The Cheerful Scapegoat”: “You could make it vanish [a stomach scar] if you were omnipotent, but you suffer, as do I, from a truncated vision.” Again, our vision is partial when it comes to the divine. This reminds me of a quote from John Ashbery’s Flow Chart where he speaks of “peaceful voices, rising / tier on tier / in the storied gothic cathedral, go unheard. Nobody thinks it’s time for them . . . ”

5. Striptease

But the world is mapped by human laws that claim to be a product of the scientific approach to nature, and rationality. When it is mapped and defined, sectioned off as a territory, through war, through the subjugation of indigenous peoples, there is the creation of nation states, laws, customs, and the nationalistic pride of the victors, who write the history books. In Koestenbaum’s world, the narrator in “Bloomsbury Revisited,” “makes friends with cineastes and buggers,” and will turn his “love of pattern into a body part as despised and lionized as Van Gogh’s ear, propped on a toilet tank to attract a loitering Salome.” Here, I was reminded of poet Adeena Karasick’s wonderful description of Salome in her book of the same name:

Throughout Christian tradition, Salomé has been tagged as an evil murderess notorious for beheading St. John the Baptist. With phallocentric fervor, she has been serially exploited by Gustave Flaubert, Charles Bryant, Oscar Wilde, Richard Strauss, forever entrenching her in social consciousness, as a dangerous woman, a praying mantis who cannibalizes the head of her lover. Here, Salomé who descended from Jewish Royalty, (the daughter of Herodias and stepdaughter of Herod Antipas, ruler of Galilee), is not appraised as a villain, but hailed a hero — a freedom fighter; . . . [who] rejoices in her sexuality, in transgressive passion and female eroticism.

In “The Artist’s Methods,” we read: “Loincloth or not, I profit from obfuscation. Therein lies my amorality.” Koestenbaum’s prose performs a kind of striptease before the King’s English, like Salome’s before King Herod: “Without nudity, I’d have no alphabet.”

6. New Vulgarities

In “Telephone Receivers or Cooking Spoons in Purple Haze,” the narrator speaks of a new “Tenderloin technology [that] will soon be invented to recreate homosexual utopias in the desert, like Marfa: new choreographies, new vulgarities.” What he is trying to do is reconstruct “the original fire.” I think of these “new choreographies” and “new vulgarities” as a transitional, borderless territory in language; off the radar, secretive, nomadic, creative, imaginative, not bound by walls, codes, laws. Koestenbaum’s language is a rupture in the linguistic system that creates, according to Deleuze, a “map of creative imagination, aesthetics, values . . . animated by unexpected eddies and surges of energy, coagulations of light, secret tunnels, and surprises.” Can we trust Silicon Valley to invent something that helps the homosexual community? There is no golden age in the past that we can return to; “a new vision has overtaken this waking nightmare that pundits call a nation.” This new revolutionary vision is Koestenbaum’s prose. After all, “We’re just lying here nude, trying to recapture some vanished essence.” Something will happen.

7. Sometimes we need to push

Paul B. Preciado, in An Apartment on Uranus (Semiotext(e), 2019) writes that within this “new supra-state techno-patriarchal governmentality managed by the financial Mafia proliferates, experimental practices of collectivization of knowledge and production are emerging.” In “The Artist’s Methods” Koestenbaum describes such an emergence; the narrator says: “I will help Valentin escape from prison. We will overthrow the government, in our own paltry fashion. We will take a boat to an unnamable island and start a new nude organization, of which Valentin will be executive director. Gulls and cormorants will serve on the board of trustees.” A fantastic vision of revolutionary politics! Paolo Virno, a member of the Autonomist paper Metropoli, who was arrested in June, 1979 wrote,

The natural corporeal reality of [the] individual, his or her socially enriched senses, instead of constituting the tedious and superfluous empirical zone in which value is produced, suggests a different criterion of productivity, no longer based on the blind necessity of self-preservation or “time-saving”, but rather on the variegated time of consciously planning activities . . . which, after all, is what Marx alluded to when he spoke of the composer of music and the work of art as anticipations in terms of a form of production without domination.

In “On not being able to paint,” the narrator writes: “There’s no end to the derision surrounding us, and we sometimes need to take action. Sometimes it’s not enough to put up with insult and expect people to change their manners. Sometimes we need to push.” We need to act or nothing will ever change.

8. The Left and the Right are in bed together

The narrator in “The Snow Falls on . . . ” says “The power relations between Sheila and me oscillate. Their non-fixity is a heavy snowfall landing right now on a tame Rottweiler . . . who is a pacifist . . . If Sheila could forge me a draft card, I’d thank her, and then I’d burn it. I speak to you as paid representative of Sheila’s dance studio, which doesn’t yet rule the land.” This is a negotiation between power and freedom. It’s always about power. But it remains a back and forth situation because while the narrator is a paid representative, he will burn the draft card which represents his contempt of the military mindset. You can’t win against the system of power, you need to subvert it from within. And what about Pacifism? Speaking of politics, in “The Greenhouse,” the narrator writes:

The greenhouse renovation crew had no love for nation-states; the crew, like the pink flower within the greenhouse, feared the arrival of totalitarianism on the palace’s grounds. The palace, no longer part of a benign monarchy, had succumbed to a new dictatorial comedian, who’d stolen the place from the deposed king, and who was initiating a set of reforms that surpassed in cruelty any of the punishments that the king had ever meted out.

But the problem is that the Left and the Right are in bed together.

9. Subtle acts of warfare against stillness and ossification

We are invested in the logic of language; we believe that it is referential and that because of that it stabilizes our view of the world. The language police uphold the status quo of “Literature,” enforcing an institutional approach to language, where it is supposed to be objective, obeying a kind of scientific method. Autofiction is the subversion of primacy of the author. The narrative “I” is not dominate, singular, enforcing a moral stance, but multiple and amoral, playing with the language and identity. This is a form of revolution. Koestenbaum writes:

When the Boston Tea Party made its statement, angering the mother country, the waves laughed, and I am now the freckled reincarnation of those happy, revolutionary waves, in a harbor built from contradictory patterns, injudicious cross-hatchings, like a horny bracelet of sighs worn by a glutton waiting for a ramshackle bus that may never arrive.

While needless wars are fought over ideologies, Koestenbaum is interested in re-framing perception to include playful, childish language in order to destabilize the language that perpetuates arguments that have no solution, like the ones the Left and Right fight over constantly (“the arid zone of diplomatic quibbling”). The narrator in “Profile of a Departed Cellist” says “We were gossips, flirts, hacks — unemployed tricksters, trying to cop a feel in the corridors of power. Would we succeed in hijacking power, or would sovereignty kick us in the gallbladder?” You must subvert the system from within. For Koestenbaum, this involves “subtle acts of warfare against stillness and ossification.” As Deleuze writes: “Lay down a map of the land; over that, set a map of political change; over that, a map of the Net, especially the counter-Net with its emphasis on clandestine information-flow and logistics.”

10. A definitive religious document of our time

Koestenbam is essentially a materialist but there is also an aspect of his writing that contains a spiritual element. Tania wonders in “Dimples in His Tie,” if the “flowers of confidentiality — asters, carnations, mullein — ripped me off by not materializing; they remained spectral. Was I enough of a loudmouth to force an intangible flower to develop an actual stamen and pistil?” Tania cannot mimic the actions of a god by allowing things to be created from nothing. The narrator writes “God punished Tania by dimpling his tie,” which suggests a certain perversity about Tania; the narrative “I” intrudes and writes: “If I, like Tania, stretch my capacities, who will punish me . . . God thinks that He is in perfect control of his retaliatory routine, but miscalculations mar his stunt; I will itemize those errors in my account, which will become the definitive religious document of our time.” This book can also be thought of a kind of perverse religious document, amoral as it is. In the following passage from the fable, “Tortoise,” the narrator invokes Eden and a “prime-mover,” casting his own version of the biblical story:

I saw a father carrying a baby on his shoulders. The father was dancing, solo, by a barren apple tree. The baby was nominally part of the dance, but only as a passive passenger, riding on the prime mover’s shoulders. I remember the flavor of that tree’s apples, before it had ceased to produce fruit. The apples had the library-richness of aged port — moldering paper, fire-places, dust. I remember those apples, scattered like a spangled skirt around the tree’s base. So abundant were the apples, we left them on the ground to rot. We regret the rot, but not the abundance.

He is speaking of the abundance of knowledge; the knowledge of our bodies as sexual but also the knowledge of books. “We regret the rot” because as a result of our knowledge we discover we are mortal, corporeal. But it was worth it and “take this much-touted ‘tragic sense of life’ and nibble it, as if it were a ginger snap.” Not too much so as not to be overwhelmed by suffering.

11. Between the “courtly expression” and the “spasm.”

In “A Page from My Intimate Journal,” the narrator says, “the tongue (if you will forgive my scientism) completed the divorce between cognition and organism.” Speech divorces the language from its relation to the body. In “Decor Analysis,” the narrator writes, “To explain these features would lead me back to Martha’s chosen radio station, the one playing dismal oldies.” To offer explanations is to revert to representational language, the objective language, where the subjective is in chains, not allowed to speak. To believe that language is referential is to suffer; to believe that language accurately describes the world is to experience failure when you discover the relation is provisional and arbitrary. Consciousness is bound up with the language. As Koestenbaum writes, “An alphabet doesn’t delineate consciousness. An alphabet creates consciousness.” But his language has the intensity of a collision between the corporeal and the linguistic. It is a supremely em-bodied language. The narrator of “A Page from My Intimate Journal” continues: “Careful’s candor, and its courtly expression, aroused in me a spasm of religious feeling.” Strange that the name of the main character in the story is Careful. Koestenbaum’s prose exists between the “courtly expression” and the “spasm.” These “fables” are perversely formal but also delightfully playful. They are Apollonian in the rigor of their destabilization of the authority of English and they are vaudevillian in their stylized hysteria and outright playfulness.

11. The mode from which poetry arises

Koestenbaum’s The Cheerful Scapegoat overturns the classical idea of the fable as containing a moral; his prose is amoral, and delights in playing with the language, destabilizing meaning, or common sense. But what is common sense? The sense common to whom? And moral law as it has been enforced over the centuries; to whom do these laws apply. To the common? Who are they? Koestenbaum is a linguistic revolutionary; we won’t find our way to a utopia if we are indebted to old, antiquated laws; it is useless to try to change or alter these laws in the accepted ways. The revolution will be in the language, in tracing the currents of meaning that flicker at the edge of consciousness, barely visible, and in playing with identity. Koestenbaum’s prose creates an irrational space, which opens up the reader to thought that is associative rather than linear or sequential; it is the mode from which poetry arises. There is nothing like it out there in the writing world.

Peter Valente is a writer, translator and filmmaker. He is the author of eleven full length books, including a translation of Nanni Balestrini’s Blackout (Commune Editions, 2017), which received a starred review in Publisher’s Weekly. His most recent book is a co-translation of Succubations and Incubations: The Selected Letters of Antonin Artaud 1945-1947 (Infinity Land Press, 2020). Forthcoming is a book of essays, Essays on the Peripheries (Punctum Books, 2020), and his translation of Nicolas Pages by Guillaume Dustan (Semiotext(e), 2022). Twenty-four of his short films have been shown at Anthology Film Archives. He is presently working on editing a book on the filmmaker Harry Smith.

This post may contain affiliate links.