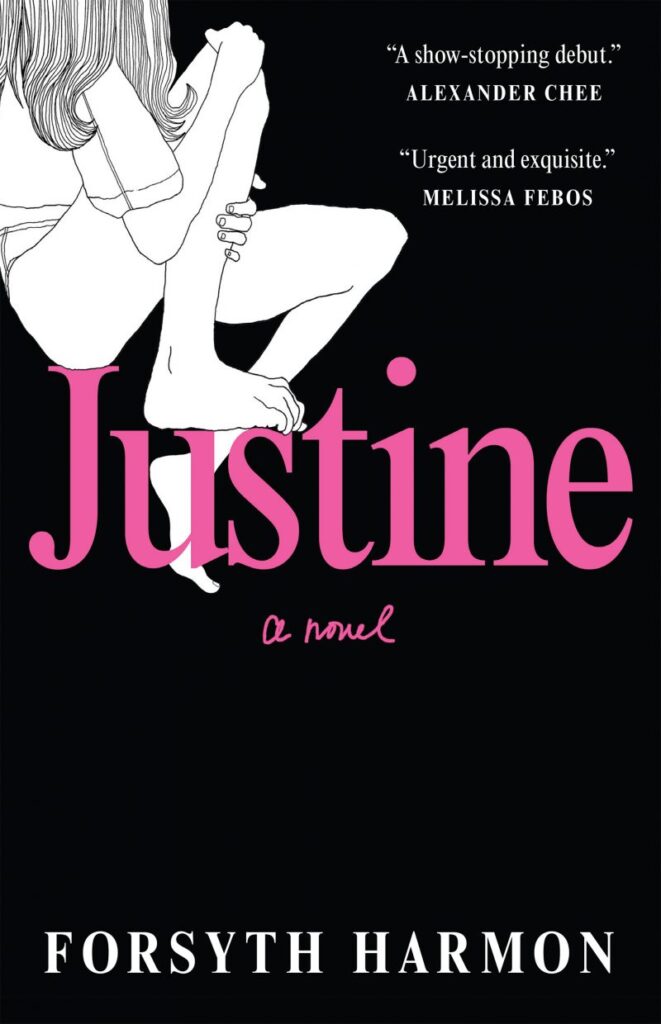

Forsyth Harmon’s debut novel from Tin House, Justine, concerns the coming-of-age of a teenager girl on Long Island. To another reader from Long Island, which I am, Justine is a painfully and painstakingly accurate representation of growing up in that place, caught between the wealth of neighborhoods you don’t live in and friends you don’t really have. For readers not from Long Island, it is still an extremely poignant novel about the loneliness, disconnection, and violence of growing up in a suburban America that is materialistically obsessed and emotionally absent.

Forsyth Harmon’s debut novel from Tin House, Justine, concerns the coming-of-age of a teenager girl on Long Island. To another reader from Long Island, which I am, Justine is a painfully and painstakingly accurate representation of growing up in that place, caught between the wealth of neighborhoods you don’t live in and friends you don’t really have. For readers not from Long Island, it is still an extremely poignant novel about the loneliness, disconnection, and violence of growing up in a suburban America that is materialistically obsessed and emotionally absent.

Harmon and I chatted over the phone about our shared point of origin, her work as an illustrator, graphic novels, indie movies, the distinctly minimalist voice of Justine‘s narrator Ali, and more.

At the time of publication, Harmon is selling some of the illustrations from Justine to benefit Girls Write Now.

Kyle Williams: If this book is any representation of your teenage experiences, we had pretty similar teenage experiences. I grew up mostly in Port Jeff Station, not far from Huntington.

Forsyth Harmon: Yes! I grew up between Northport, Centerport, and Huntington Station, where my mother, grandmother, and father lived, respectively.

I love how you captured Long Island. I was constantly struck by your portrayal of growing up in that place. Every few pages I felt myself reacting, like, “Oh, I too broke into the Kings Park Psychiatric Center.”

How wonderful! I don’t feel like Long Island gets a lot of representation in contemporary fiction. I recently read Colson Whitehead’s Sag Harbor, but it’s a bit different, being about a vacation community. I was excited by the prospect of creating the character of Long Island.

It’s quite a character! But I did want to start talking more about how this is your debut novel, but it’s not actually the first book you’ve worked on. In 2017 you had The Art of the Affair, with Catherine Lacey, and you have the collaboration with Melissa Febos in Girlhood later in March. Did that project influence how you thought about this one, or prepare you in some way for your debut?

I’m really grateful for that first experience with Catherine Lacey. She is a brilliant mind and was a fabulous collaborator. The way we worked together was really organic. She drove the vision of the project, but we co-curated which personages would appear. If you’ve looked at the book, it explores several chains of relationship between writers and artists, and it was fun to collaborate on who to include in each. Tactically, I learned a lot about publishing, which did give me some preparation for this debut. Although of course when it’s just my name on the cover – I do feel more accountability – and vulnerability.

Did you feel any sort of translation from your artistic practice to your writing practice when you started Justine?

I’ve always done both writing and illustration. I worked on the project that became Justine throughout both my collaborations with Catherine Lacey and Melissa Febos. I really enjoy moving between writing and illustration practices. They use different energy, or different parts of my brain. With Justine, the writing kicked up some dust. I did lose a dear friend, so there was an emotional load to the work of writing. But illustration was a more mellow, meditative process, which allowed for the dust I kicked up to settle. Being able to move back and forth has brought a nice balance to my creative process.

I’m sorry to hear about your friend. I know what that’s like.

I don’t think I really processed it much at the time. I think the project helped me do that. And I wanted Ali’s experience to feel true to mine. She’s not, you’ll notice, deeply reflective and full of, like, adult wisdom. I didn’t give her that small bit of wisdom I hope I’ve since acquired. I tried to make the experience immediate to the perspective of someone that young who – even for that age – isn’t a great communicator.

I think you captured that so well. I love the starkness of the sentence structure in this book. I don’t mean that it’s halting in any way, but that immediacy really does come through and feels very accurate to the teenage experience.

I appreciate that. My husband, who is also a writer, called it a kind of teenage Hemingway voice. Generous of him. I was also inspired by 90s indie films. Hal Hartley and Gregg Araki. There was this choppy kind of violence and discomfort to a lot of those films. But in grad school I got a lot of flak for the lack of interiority.

I wanted the images to add mood, and to show how Ali saw the world. Of course, they’re black and white, and so might reflect a black and white way of thinking. They’re mostly up close, showing, perhaps, a lack of perspective. I also worked with a few series of images: a cassette tape or a measuring tape unraveling, a Tamagotchi pet dying.

That was actually going to be my next question. There’s a really wonderful parallel between the way the images work with the voice of the text. They both have this fine- and stark-lined quality to them. Do you feel that the images are illustrative of the text or constitutive as pieces in themselves? Or somewhere between?

Somewhere in between. I would make a distinction between this and a traditional graphic novel, where often the images really are exactly illustrative of what’s happening. I’m not working in a cell-based grid; I’m not necessarily aligning the text with the image one-to-one. I tried to have the images cement us in a certain time and place – there are a lot of cult objects of 90s adolescence – while also emoting for my narrator. It wasn’t a mistake that I didn’t show faces or full bodies, either: Ali is cut off, she’s disconnected. But in Ghost World, let’s say, because that was a big influence for me – you see the characters’ bodies and faces as they move through the narrative. The pitch for this book could be, like, halfway between Daniel Clowes’s Ghost World and Julie Buntin’s Marlena – somewhere between the traditional novel and graphic novel. Illustrated literature hasn’t really been popular since the nineteenth century. I would like to open the discussion around that form again, to see what we can do with it.

What examples are you thinking of? Like, Alice in Wonderland?

That’s a great example. And Dickens was illustrated. A lot of his work was serial, so I’ll mention here that I’m working on a second and third book, looking at Justine as a trilogy. But I hadn’t made that connection between illustration and serialization until just now. I’ll have to think more about that. Now my head is in A Christmas Carol.

To bring us back, a little bit, to the writing: It’s really harsh. You mentioned that there’s a specific lack of interiority for your character, so it’s really action and the outer world that we’re seeing portrayed. And it feels like a particularly harsh version of American teenagehood. It’s very different from what we might see in, like, a John Hughes movie. I wanted to ask you about the violence of being a teenager, and how you were thinking about approaching that.

I think that violence is true to my felt experience as a teenager. There’s something violent about that time in life, when our bodies are changing, and also the way the world treats us is changing. As a woman, or as a girl becoming a woman, the attention one gets from men – and from women – might gain a kind of violence that isn’t there prior.

I’m thinking immediately of the weight chart that appears toward the end.

Yes: eating disorders as an attempt to bring some control to the chaos of that time. And perhaps as an attempt to step out of that transition, to say “I’m not sure womanhood is something I want to approach, having felt some of what that could mean. It feels burdensome.”

I should acknowledge that Ali is not particularly underprivileged – obviously there are teenagehoods far more challenging than hers. But she is going through a difficult period. She’s in mourning, she’s disconnected, she is kind of living in absentia. I wanted those silences to speak too, and in that way there is a minimalist project here.

You spent quite a lot of words on brand names. Which connects to the history of minimalism, as with that K-Mart Realist vibe that came about in connection with Gordon Lish’s minimalist project, but how were you thinking about the branding in this book?

Ali’s growing up in a small, conservative town that glorifies material displays of wealth but forbids any frank conversations about class. She has no words for her burgeoning consciousness of difference. And so brands, objects, and neighborhoods – as geographies of wealth – become markers of differentiation and also promises of escape. She imagines that if she can associate herself with these objects that are representative of a different kind of life, perhaps she’ll live that life.

Which is, right, the same as the popular imagination of marketing.

And it’s successful with Ali.

And with me too, probably.

Yeah, same. It’s very American but there is a particular bling-flashing culture on Long Island. I feel like it could have something to do with being geographically close to New York City, but culturally very far away. Just look at 2016 and 2020 voting results for Nassau and Suffolk counties.

Yes. And thinking about Lee Zeldin will probably pop our heads right off.

Yes. In 2020, Nassau and Suffolk were the wealthiest counties to vote for Donald Trump in the whole country.

Long Island is a tricky place. And I think, like Ali growing up, I was in it. I was not aware of the racism and the misogyny and the homophobia, I was just breathing the air that I lived in. Leaving gave me some perspective, but the last two elections took that perspective to a different place, or a different depth. It helped me to see how much work I have to do.

I doubt I was myself cognizant of those prejudices as I am now.

At the same time, I did want to be conscious about how I treated Long Island. Alexander Chee talks about being sensitive to our communities of origin. I wanted to show the starkness of Ali’s experience and the facts of her life in that place without, at the same time, bringing judgment on it. This isn’t a satire.

Do you feel in some way like the craft of your writing has been shaped to Long Island, or like you’re trying to make a shape of Long Island through the writing itself?

I think the characters drive the narrative. So much of the language comes from the way Ali and her grandmother communicate, or fail to. Ali was taught to speak by, and spent the most time with, a person for whom English is a second language, and who besides that may lack certain emotional tools. A big part of Ali’s shortness and her inability to move to the interior comes from that training. But perhaps there’s something to Long Island shaping the writing, too: that strip mall landscape. There is a kind of staccato to stopping at light after light on Jericho Turnpike.

I was inspired by the music of the time, too. Justine loves The Smiths, and another character is obsessed with tristate hip hop, like the Native Tongues collective. I made a soundtrack to the book, which you can listen to and read about at Largehearted Boy.

Earlier you talked about Ali being not a particularly underprivileged teenager, but there is a gradation in her experience. I love that one line of Ali realizing she literally lives on the wrong side of the tracks – as a moment of interiority that she can only express through a kind of cliche, but a nonetheless true cliche.

Yes. Moving from the coast to the interior, crossing the Long Island Railroad, there is a sense of class demarcation and racial segregation.

So when you talk about Ali being not particularly underprivileged, which is true, but still thinking about that gradation, there is nonetheless a sense to which Ali is still being othered by a world that she wants access to but can’t enter, a world of being even more distinctly privileged than her peers.

Yes. Ali lives through comparison. Her sense of worth is informed by what she sees from her peers, or from Vogue magazine. Inevitably this devolves into a kind of fantasy wherein the Prada shoe can mark her body explicitly as belonging to the world she believes she doesn’t otherwise have access to.

One last question that I think we can end on. We were talking about contemporary representations of Long Island in literature, but there are also a few really good canonical ones. You make reference to the Walt Whitman Mall, for instance, which is maybe one of the most boring malls in America but also one of the most hilariously named.

Yes! We took so many school field trips to his birth place across the street.

But also, and this is maybe so obvious as to be too obvious, but, The Great Gatsby, right? I was thinking of that book a lot while reading Justine.

Yeah. Thinking about Nick as an observer, as someone who puts himself close to relative wealth, watches it, and finds himself carried away by it. The beautiful shirts thing – that’s real for me, and that’s real for Ali. Reveling in the escape of objects of beauty, whether it’s a Prada shoe or it’s Justine herself. But of course, what happens when we turn people into objects?

Justine

Justine

Forsyth Harmon

Tin House

March 2021

Kyle Williams is a writer living in Brooklyn. He is an MFA Candidate at UT Austin’s Michener Center, Interviews Editor for Full Stop, Director of Communications for Chicago Review of Books, and A Public Space’s 2019 Emerging Writer Fellow. He is on Twitter @kylecangogh.

This post may contain affiliate links.