(c) Erin Dowding

On the eve of revolution there is Talking Animals: Joni Murphy’s new novel deprogramming the Anthropocene. An ineffectual bureaucrat in an increasingly privatized public sector stumbles his way into a conspiracy driven by greed and prejudice, and also he is an alpaca. Joni Murphy has taken the critical eye from her 2016 debut Double Teenage to craft a fable about blossoming political consciousness and systemic violence. It may be exactly the kind of novel we need right now. Joni and I talked about that political consciousness sitting, socially distant, across from one other at a long table in the “Politics and Philosophy” room at the currently closed-to-the-public City Point location of McNally Jackson. In a New York City that has, with the rest of the world, seen a radical change of life in the last few months, Talking Animal presents a hopeful vision of what coming to consciousness in desperate times could look like. And it’s tempered with really, really good animal puns—like the French feminist-philosopher cow, which I may never get off the floor from.

Kyle Williams: At some point in the lead-up to this interview—which was extensive, because the world has ended a few times since we first connected—you called your book “gentle and silly.” I’m curious about that description, because it is about animals, its main character is Alfonzo the Alpaca, but I do not think it’s particularly gentle or silly. By its end, it’s about revolutionary politics. What about it feels gentle to you?

Joni Murphy: It’s interesting to even be in this room. There’s all the Frankfurt School over there, and The Last Days of the Inca is on the shelf behind me . . .

“Gentle and silly” may not be the right words, I definitely don’t think capitalism and the destruction of livable physical and psychological landscapes is silly.

What I wanted was to create a delicate frame for devastating subjects. This is an approach from children’s books: Use animals as a mode of examining death and loss, language and community. The animals bring levity. Alpacas and llamas are somewhat goofy animals: they’re non-threatening and because of that they’re easier to imagine with generosity.

There’s an absurdity in imagining an alpaca as a failed academic and angsty, angry bureaucrat. Many people, maybe most, can feel sympathy with animals more freely than with other humans, because we see them as vulnerable, or impressive, or just other. With human characters, the politics of it might have been too harsh. But by talking about revolution with animal characters, as a fable or a fairy-tale, It’s a softer focus.

Also, I think it’s gentle in terms of how I miniaturized things. In real life the scale of horror we are facing is paralyzing. People are coming to revolutionary politics because things are so bad. The history of colonial, post-colonial, neoliberal, capitalist violence is so long, and so complete, and so brutalizing. Combine this with the collapse of the animal world, mass extinction—these issues are too profoundly huge to take in. Thinking about all the species that have been lost, the sublime nature of what we’re losing and what’s at stake, I found I couldn’t write about it directly. By miniaturizing and making the characters animals, I could bear to think of it.

That exact issue of the incomprehensibility of the statistics of death is playing out right now in real-time.

Exactly. I read an article about the Trump rally in Oklahoma and they interviewed a man who said he wasn’t afraid because he’d “never met anyone who has Covid.” And though we might think that’s ridiculous, most of us operate more that way than not. A recession feels more real when it’s us and our friends losing our jobs. Cancer feels more real when it’s someone close who gets sick.

You called your book a fable, just now. I’ve seen it called an allegory, or a parable. I can already tell just by the look on your face that you have a lot of thought about these words. How do you reckon with the word “fable”? Does this book have a moral?

I think fable Kafka’s sense is what I was aiming for. The book with the biggest influence on this one was Amerika. He wrote a fable or parable about the American dream and conjured a city he never visited. Kafka’s version of New York—no one who has ever been to the city would write what he did. But I appreciate this incorrect New York. There’s this coming-to-consciousness narrative, but the book is unfinished, so you don’t get to see what happens after consciousness is come to.

I don’t want to bring up Zizek in this interview.

There’s like an entire shelf of Zizek behind you.

My husband recently described Zizek as “theory for dummies” and now I can’t get it out of my head. But I kind of like some of his books! But he has a famous line, which he might have cribbed from Fredric Jameson: It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than it is to imagine the end of capitalism. Maybe that’s the moral. Or maybe it’s that we have to imagine this. This book kind of ends on that idea: they don’t know what comes next, but it can’t be what it has been. The way American modernity, the western tradition has trained us to think, to interact with one another and the world, is not working. It’s catastrophic. So it’s necessary to try to imagine the alternative to just the end.

Imagination for a lot of people ends with communism as it’s already existed. I’m more interested in what we can’t imagine but are trying to.

It was maybe an unfair question to ask about fables and morals, and bringing up Kafka is a good point. He often wrote fables, but whether or not they have morals is hard to say. Probably the worst readings of Kafka are the moral searches: The third judge represents this specific failure of bureaucracy, or something.

Kafka was so much more mystical, and mysterious. He had an ethical, moral sense, but there aren’t clear lessons. His works are much more like puzzles or objects to meditate on. He was also a worker, so the labyrinths of bureaucracy were real to him in his day job, just as the mythical elements were real in his writing.

There’s this recording of the scholar Howard Caygill, where he argued Amerika was Kafka imagining the United States through the lens of its violence, of workplace accidents and of lynching of Black Americans specifically. That America is so much different than the myth of America. It’s not golden streets, it’s unpredictability and invisibility. The Statue of Liberty is holding a sword. Caygill’s interpretation touched me. Kafka was actually in touch with a truer version of America, even though he never came here.

Even if you look at Animal Farm, which does seem to have a message, “Those pigs and thus Stalinism is bad”—this does the book a disservice. Animal Farm was really co-opted in the Cold War as this perfect book for high schoolers about how communism can only fail. But the book is so much more about specific failures than a general one.

As though you could actually sit down and read Orwell and say he obviously thinks capitalism is the way.

His work has been misused. He’s not perfect, but you can’t call him pro-capitalist. The Cold War did a number on the education system of this country. My next book seems like it’s going to be about that.

That’s not what this book is about? If we’re thinking about the different ways of failing, in and of the capitalist system, that this book presents.

Failure is an important part of this book, especially the mismatch between education and work. I guess that’s something that hurts personally but also feels generational.

If you study critical theory in university, you’re given all these tools to seriously and critically think about how society and power works. It’s exciting and destabilizing. But then you get to the end and it’s as though you’re told by the academy to stop.

The way universities treat adjuncts is a good example. The institution does not want students to apply their critical thinking skills—the skills they often acquire in class—to the working conditions of the university. Maybe you took political theory at university, but administrators definitely don’t want their employees seeing the university as a site of struggle.

I have some unresolved anger towards the older generation of teachers who at once gave great gifts but have also in many instances turned away from student struggles. And the fact that universities have been taken over by business people is just another aspect of this betrayal that was really perpetrated over the last thirty or forty years.

I love the university for its potential, as a shelter for possible alternatives. But I’m also at a loss. Like, what does the university do now? Is it just a place where one is taught to be more employable? It’s been co-opted, as though the use of education is to get a job in the capitalist system, which maybe cares if you’re employed, but does not care if you stay alive. With Alfonzo the alpaca, he’s trying to get out or rather in: he thinks if he does well theoretically, he’ll save himself. And he fails, or is failed by school.

The failure of the academy is portrayed so well in this book. One is told to pursue higher education, but finds the gate closed.

And that’s Kafka! That’s “Before the Law.” The endless waiting to be allowed inside. The university is always promising something more, but what that is phantasmal. It’s also painful, thinking about all the laws we stand before that are presented as choices, like, ‘well you can always walk away’ but if you do, you’ve failed.

Painful especially here, because you can tell that Alfonzo has done a lot of the work, that he knows his shit.

Many of the smartest people I know were at some point kind of ground down by academia. And either they’ve kept working there, or they’ve walked away, but in both cases there was damage from debt, wild competition, from contorting their ideas into career savvy specialization. Not to say it hurts everyone, but there’s a lot of potential for that. I probably felt more sympathetically for Alfonzo as a guy who couldn’t make it through his degree than is maybe healthy or stylish from a literary standpoint.

Well, true literature is when you only write despicable characters.

I can’t. There are so many real people to hate, I can’t bear to conjure fictional characters that I also dislike. Why would I want to do that to myself? I personally need to conjure a world in fiction that gives me some relief and hope. I’m not calling out any writers in particular or anything—I don’t want to get in trouble—but so much of the popular literature right now focuses on self-hating or miserable characters. Reading too many works like this makes me feel bad. It’s like a Todd Solondz movie or something, at a certain point I can’t do it. Especially when the real dominant narrative in politics and culture are also dominated by gross monsters. It’s too nihilistic, too jaded. And there’s a helplessness it provokes. That mode of nihilistic inaction is actually exactly what capitalism wants from you—it’s not avant-garde to hate others or yourself, it fits conveniently within the existing power structures.

Cool detachment is not leading us anywhere.

Right. I want to write characters close to people I care about, who are willing to lay themselves on the line for one another; I think that’s what we need. Maybe I love my characters too much, but I don’t know. I want the characters to want change, and a more radical change than from one kind of self-hatred to another, more mild self-hatred.

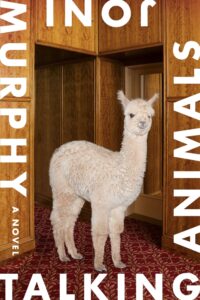

Looking at animals is therapeutic. I mean, look at the alpaca on the cover, he’s so cute and sweet.

The alpaca is very cuddly. Though I did wonder how he, like, typed?

Slowly. He’d have to hunt and peck with those toes. Typing would be an effort but he could totally do it.

The society presented in this book is really interesting. You’ve done a lot of work to present the geopolitical histories of the animals in this book, in ways that mirror human history—the depth of research is really palpable. But, if we’re already accepting the fableist narrative, which usually, intentionally, leaves out that kind of information, I’m curious about why you’ve done that work.

I was trying to work between the ways in which animals appeared or been used in literature. One approach is making animals a symbol of something human. To use Animal Farm as an example again: Each pig stands in for a real historical figure—Lenin, Stalin, Trotsky. The sheep are the proletariat. Etc. It’s pretty one-to-one. A lot of animal stories are presented in this way: cats represent women, dogs men, or mice represent the poor, etc. Another framing of animals posits they are totally other, alien, free, outside our world. This would be the anti-anthropomorphic, traditional science fiction that tells us to look at animals as specific and alien.

But there is such a thing as Animal history. It both entwined with human history but also its own. Animals Studies make this clear and there are animal researchers like Frans B. M. de Waal who say we should most definitely think of animal emotion and intelligence more like our own than not.

Alpacas and llamas have a history. It’s one shaped by invasion, enslavement, murder—colonialism. They aren’t symbolic of the human victims of colonialism in the book, I’m trying my hardest to speak of their trajectory, with a slightly human bent to make it legible. They have been implicated in the colonial project. Real alpacas have been moved around the world, and have had to resettle as a kind of immigrant animal in Australia, Europe, or New York State. They’re all over, working, forming relationships, and they’re totally removed from the land they evolved in. It must be as destabilizing to them as to us. How could the alpaca consciousness not be affected by all this?

The binary between nature and culture is a false one, and there’s this idea in it that animals are somehow untouched by history, but that’s ridiculous. Animals do not exist outside of culture, outside of history, outside of labor. So many animals have jobs!

I wanted to think about animals as subjects of their own histories, not just as passive objects within human dramas.

The work that Alfonzo does in the book, of sitting down and writing his story, is messy and complicated. He wants to write this crazy, beautiful, messy academic book that no one reads. And I love academic books like that. I think academics, critical theorists, are the people doing the smartest work with the smallest readership.

That’s such a beautifully sad way of putting it, “the smartest work with the smallest readership,” especially looking at this wall behind you of all these philosophers and theorists really putting themselves on the line. I would love to talk about the influence of critical theory on your writing. It’s obviously there, in both this book and the form-bending from your last book Double Teenage. What’s the attraction to critical theory, and how are you thinking about using it while writing fiction?

The short answer is that before I did my MFA I did a master’s in Cultural Studies. My thesis was about Benjamin’s radio works for children, about inserting his philosophical ideas into the frame of fairy tales. Since then I’ve always read casually around the edges of theory.

Benjamin is a big influence, even though he’s one of those lauded thinkers who’s beyond. But the charming thing is he also represents someone who succeeded because of failure. It was fortuitous, for us, that he never got a professorship. He wanted one; he spent his youth assuming he would become an academic, that he would spend his time writing philosophy for other specialists. But his dissertation was rejected and that kind of sent him into a crisis. It forced him to work differently—he had to write for a more general audience: magazine articles, radio pieces, reviews. You can see how this instability was wildly difficult for him personally but it was good for his work.

Benjamin is always there in the background, but if we’re talking specifics, I was reading Georgio Agambin, Oxana Timofeeva, David Graeber, Silvia Federici, Eduardo Galeano, Wendy Brown, and David Graeber among others. Theory was kind of floating around amidst animal puns.

More generally, I think the best theory showed me that you can write compelling stories that focus more on systems or themes than on individuals. In writing classes you often encounter weird assumptions about choice and individual personality. Something I’m proud of about my fiction is that my characters aren’t special or exceptional. I want to write non-heroic literature. This felt especially important in crafting a novel about New York. The city is weighted down by exceptionalism. It’s the city with either degradation or brilliance. There’s the horror show or the art show. Towering figures or collapse.

But living here what I see is that the building and maintenance of life in New York has more to do with collaboration and an everyday-ness. The book Working-Class New York by Joshua Freedman was helpful in seeing how the city is carried along by a powerful through-line of working people. The power is in the collective, or the herd.

The idea of the special individual does real harm: the idea that one character is a culmination of all their special, brilliant, or shitty choices just supports the dominant ideology. It folds into the American fixation on private property and choice. The CIA involvement in the culture industry during the Cold War was not accidental. They knew art was a powerful means of promoting the individual. I mean: Why is American Literature? Why is Iowa?

Reading nonfiction, critical theory and also spiritual practices have helped me at least ask questions about individuality, how and if it really exists. And I guess that’s what I’m trying to do: work against the training.

Maybe it works, maybe it doesn’t, but at least the question is there.

Right, as though the core of American fiction is still this Victorian idea that the weather outside is a reflection of the protagonist’s inner turmoil. We’ve just found better ways of dressing it up.

Yes! And this plays out so often as an inside outside dualism. Like the weather is either symbolic and reflecting the character or it’s a completely outside force, cruel and indifferent.

Animals have been treated this way as well. Animals are used as these artistic devices to make a point about humanity. But this becomes the set up for so much violence. We are still so influenced by the Cartesian concept of animals as living machines. As I was researching for the book I was continually dismayed at how often I encountered some version of the “Do animals feel pain?” framing, and not in historical documents but in contemporary writing. That is a fucking psychotic question and it’s easy to see how it extends to questions like, “Do women feel pain?” or, “Do black people feel pain?” These questions have real material effects. They provoke answers like, “They don’t feel pain like we do,” which become justifications like, “It’s okay to treat this other being roughly, or in some way I would never want to be treated, because they don’t feel in a way I perceive as real.” The hierarchy, the ongoing conversation of whether or not the Other is even real, is so foundational to Western society. It’s still in circulation, I mean obviously.

Recognizing and grappling with entwinement, between us and the weather, between us and the Other seems like the only way forward. If we reduce others to symbols or objects we only end up hurting ourselves. We are all animals in this system.

Which is all a roundabout way of saying, I’m not interested in being a part of the tradition of psychological realism.

Talking Animals

Talking Animals

Joni Murphy

FSG Originals

August 4, 2020

Kyle Williams is a writer living in Brooklyn. He is an MFA Candidate at UT Austin’s Michener Center, Interviews Editor for Full Stop, Director of Communications for Chicago Review of Books, and A Public Space’s 2019 Emerging Writer Fellow. He is on Twitter @kylecangogh.

This post may contain affiliate links.