Familiarity with the immortals of the Western canon comes with a stale peril for the minority reader: the inevitable hatreds lurking in the decomposing hearts of past luminaries. Loving, identifying, or projecting yourself onto the work of creators who professed hostility for your kind is a treacherous intimacy; your unimagined, unwanted embraces mingling with prejudices from beyond the grave.

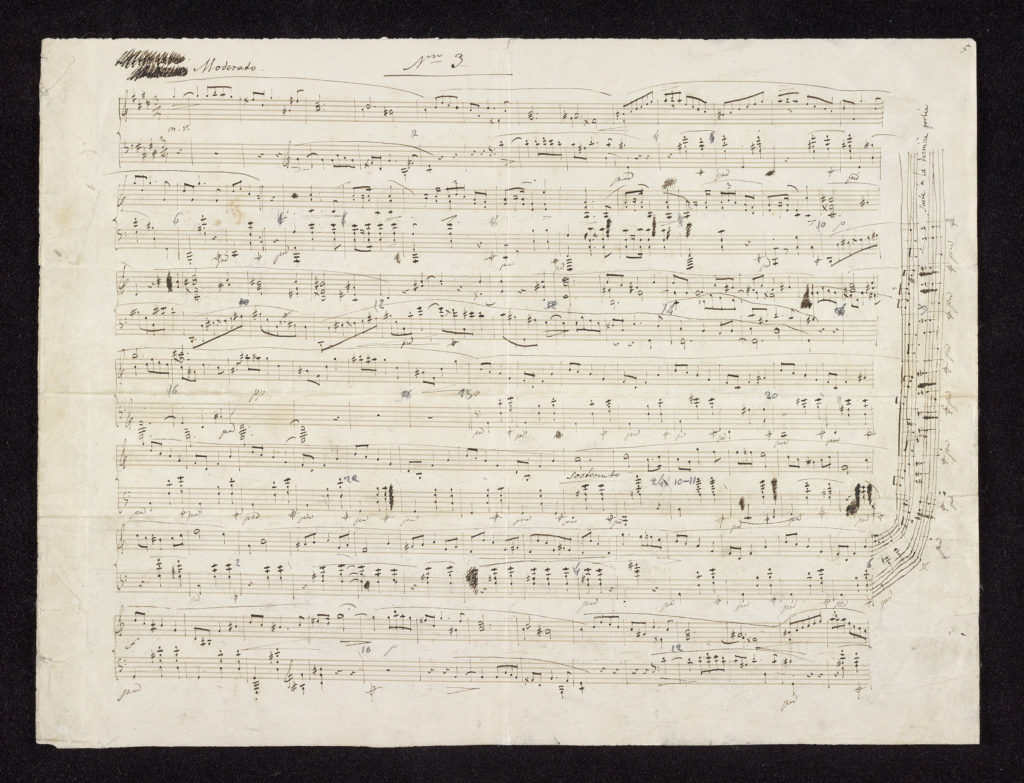

Jews will be Jews and Huns will be Huns—that’s the truth of it, Chopin declares in his private correspondence. But what can one do? I’m forced to deal with them, he concludes, anticipating my relationship with his words. Disappointed, I try to assess which antisemite lurks beneath his music: the general or particular one. Was he only as antisemitic as his contemporary countrymen? Or was his antisemitism all his own, inventive, high-strung, melancholic, tubercular? I want to ignore these possibilities.

His correspondence anticipates this, too: Every difficulty slurred over will be a ghost to disturb your repose later on.

I would resist the strategy of subversion, a too-ready and somewhat tired tool, but my particular regard for his music is undeniably subversive. I consume and project myself onto his work in ways that violate responsible hierarchies of classical music listenership.

Oscar Wilde plainly leads the charge, admitting that after playing Chopin, he feels as if I had been weeping over sins that I had never committed, and mourning over tragedies that were not my own, neatly condensing the liturgical nature of my own listening. If I emoted as completely through my actual prayers as I did listening to Chopin—weeping over my sins, mourning over my own tragedies both inherited and appropriated—I wouldn’t have to consign the possibility of being a better correspondent to God to some indefinite period in the future.

On the subject of prayer, Anne Lamott has created a useful rubric of types: Help, Thanks, and Wow. Prayer via Romantic-era composer presents emotionally rangier prospects, hashed out in terms of sensibilities germane to the moods and modes of Jewish prayer, obsessive over certain refrains, prone to morbid reflection before veering into sudden, delirious ecstasies.

I directly and unironically invocate through the unruly contents of his music, sarcastic, tender, self-serious, now needy, now indifferent, well-tailored, well-upholstered, provocative veins of desperation, come-ons tarted up as sparkling rejections, breathless reconciliations and placid horizons hinting at the previous destruction of entirely private worlds. Sometimes, he just sounds like an excited or worried music box; long after it has wound down, I find myself thinking of it.

In my ear his music becomes an oddly creolized thing, in conversation with people and places with whom he had no desire to speak. The voices of great cantors of yore sing through his sinuous melodic lines, the loose, declarative rhythm of their pleas with the eternal. He is not as far away from us as he would prefer to place himself, his moody, exotic essays of national dance drifting easily into coterritorial Jewish habitations. Even these reckless, improbable fancies warrant a response from him: he charges contemporary Jewish music with the criminal offense of masquerading as Polish music to entice the masses.

While writing what you are reading now, the revelation I think of Chopin, Chopin doesn’t think of me resounded like a melodic crack of thunder. But I am unsure that this is true. Perhaps the composer said it best: Indeed, I write to you from a strange place.

❦

Anthony (Mordechai Tzvi) Russell is a performer, composer, and arranger of music in the Yiddish language. He has been a contributor to The Forward, Tablet Magazine, JTA, PROTOCOLS and, recently, Jewish Currents. He lives with his husband in Massachusetts.

This post may contain affiliate links.