My dad inherits pieces of strangers’ lives: cryptic notes and self-aware love letters, mostly-blank diaries, birth certificates and driver’s licenses, dirty films with names like “G-String” and “Perversion” scrawled on the cases, packets from the United States Armed Forces on “returning to civilian life,” and enough rusting sleds and tricycles to represent every decade of occupancy. He leaves the sleds and tricycles out to disappear from the curbs of their former homes. But the other stuff is harder to purge; it comes with a set of ethics.

What’s the right thing to do with history that’s not your own? Should you apply different treatments to the shared cultural artifacts (newspapers, coupons, books) versus the personal ones (a handwritten Christmas Dinner menu, a baby photo, a folder of school assignments)? And where do you draw the line between the two?

My dad is a general contractor, forever entering the room holding some obscure construction object and asking, “Any guesses what this is?” The answer rarely sheds any light on its functional purpose: a “Teco hanger,” a “hurricane strap.” He buys properties that no one else would dare touch, aside from leveling them and starting from scratch. Usually, it’s a foreclosure. Or someone died and the inheritors want nothing to do with it, foreseeing a Pandora’s box of multi-generational hoarding. But there’s joy in restoring a home that has stood longer than the oldest trees on the block, and he taps his reserves of patience to salvage them.

Before any construction can happen, there is the endeavor of emptying: Sifting, scraping, sorting through generations of refuse. Men move through the space with the darting eyes of tomb raiders, afraid of rats and snakes and secrets, dreaming of cash sewn into stained mattresses. As in geochronology, the oldest layer is at the bottom; Pre-Anthropocene America slipping through loose floorboards and disintegrating in mouse-infested drawers.

At the house on River Road, loose photographs reveal three generations of ownership. The original patriarch is unearthed, gazing out from beneath the brim of a bowler hat. In his family’s junk mail and newspaper clippings, a transforming society struggles to define itself:

1899. A pro-temperance columnist for The Philadelphia Inquirer shares a recipe for lobster Newburg minus the alcohol: “As the wine is what gives the characteristic flavor to lobster Newburg, do not expect this to resemble the Newburg favorite in anything but appearance and manner of preparation.”

1945. A moth-eaten poster from an issue of Esquire depicts the “Great Disaster of 1906.” Looking down from a San Francisco hilltop, Victorian town houses distend and slump at unnatural angles. A fractured telephone pole collapses against a trolley car. The only figure with a face grasps a china teapot, frozen outside his burning home in a knee-deep pile of belongings: multiple chairs, a tuba, a birdcage, an upturned clock. The reverse-side of the poster is a blue-eyed pinup girl.

Undated. A mailed coupon for H.W. Long’s “Sane Sex Life” urges newlyweds to buy his book or fail at marraige. “Will your marriage be wrecked by ignorance of the intimate details of married life? Or will you fortify yourself with the proper sex knowledge to insure your future happiness?” The book is published by Eugenics Publishing Company, New York. In chilling italics at the top of the mailer are the words, “For the Good of the Race.”

While cleaning out a closet, alone, my dad finds a plastic garment bag fused shut by decades of 90-degree New Jersey summers, a thick layer of dust clinging to its shoulders. As he rips it open to reveal a wedding dress, the bedroom door slams shut. He smooths the plastic over the dress and hangs it back in the closet — then walks slowly out of the bedroom, out of the house, and drives home. When he returns to River Road later that week, the main excavator on the job has nailed a cross above the entryway and sprinkled holy water from his church around the foundation.

My mom and sister and I visit the job site one afternoon, and my dad hauls out a trunk of artifacts he can’t throw away yet. “It’s very sad,” he says more than once as a reminder or an apology or both. These are people’s lives. Hungry for something salacious but tempered by guilt, I focus on a deteriorating newspaper. It’s easier to justify the prying: a newspaper is a public artifact. The Philadelphia Inquirer from Wednesday morning of April 19, 1899 is in such bad shape that reconstructive surgery is out of the question and dissection is the next best option. I carefully separate stuck-together paper with an X-Acto knife to reveal a centerfold advertisement, calling on all “Weak Men.”

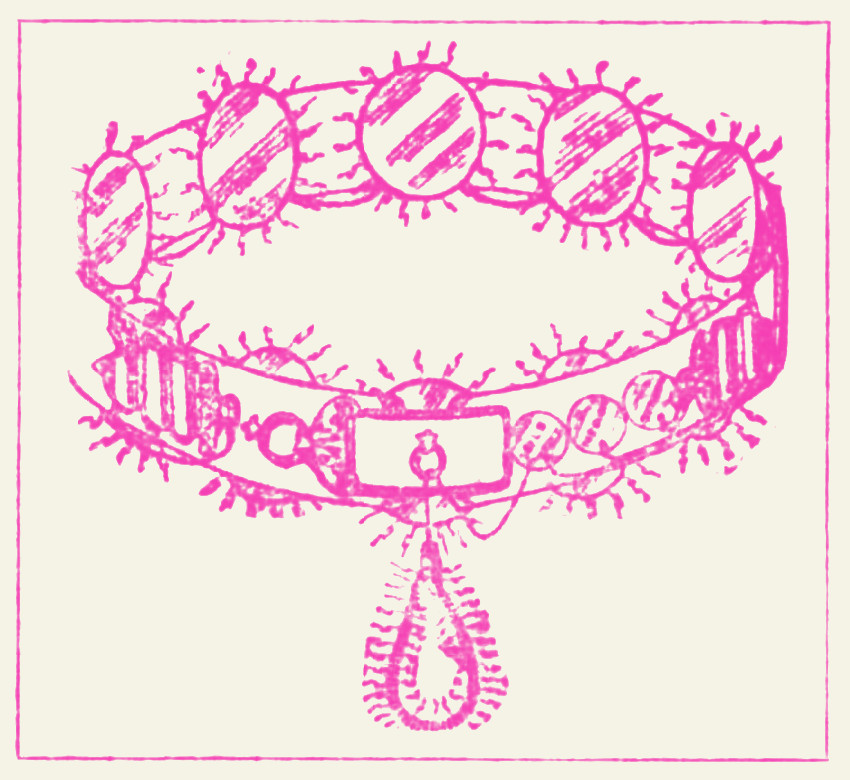

The featured product is Dr. A. B. Sanden’s Electric Belt, a now-defunct cure-all from an era when electricity was king. You can still find the illustrated patents online, where the advertised “special attachment for men” is referenced more specifically as an “electro-spiral suspensory,” a label that gets the point across without actually having to say “electric penis noose.” Sanden himself, drawn with stringy mutton chops and a furrowed brow, makes an appeal to the weak male readers of The Philadelphia Inquirer: “If you would care for an honest opinion of your case free from quack methods, either call at my office or write for my book, ‘Three classes of Men,’ sent free, sealed by mail.”

I wonder if the books were sent in discrete envelopes. Did men hide their Electric Belts from their wives and mothers, or did they wear them with pride? Did they trade horror stories amongst themselves or were they too embarrassed to admit they’d been scammed? According to Sanden, the at-home treatment packed enough magical power to have “restored vigor to 6000 during 1898 who suffered from the effects of youthful errors or later excesses.”

Was the man in the bowler hat — the first to live in the house on River Road — reading The Philadelphia Inquirer on Wednesday morning of April 19, 1899? He might’ve searched his past for “youthful errors” or his present for more recent “excesses,” and upon encountering them, red-faced, checked himself for signs of depleted vigor. It was a rapidly modernizing world on the eve of the 20th century, much faster than the one his father had known, and he would need to move through it with machine-like fortitude to keep up. Did his self-doubt propel him to Dr. Sanden’s Philadelphia office on 924 Chestnut Street?

I look up the address to imagine where he would’ve disembarked, but 924 Chestnut is now an unassuming FedEx Office, and Dr. Sanden’s electric belt has been out of production for more than a century. During a 1914 hearing, the Sanden Electric Company was exposed for defrauding the public, and his panacea for the man of the modern era has since been replaced by dietary supplements and healthtech wearables. Sanden’s Electric Belt was banished to the realm of ephemera and commercial flops, while its peer inventions (the mechanical cash register, the dishwasher) rushed unimpeded into the future.

Two weeks from now, Sanden might find himself splayed open, curbside, atop of a stack of newspapers, his unmoving mutton-chopped countenance staring up at the brilliant 21st century sky. Thoroughly emasculated, and thinking, probably, “This is not how I’d have liked to be remembered.”

Sanden could not have predicted his own posthumous circumstances any more than the three generations of New Jerseyans who unwittingly preserved his memory at the bottom of a drawer. Long before death, before foreclosure and disuse, before their private belongings ended up outside the house crowned with a “FREE” sign, their preoccupations and anxieties were immortalized in objects that would outlive their owners, changing hands over and over until forgotten or discarded.

My uncle, a mid-century modern design aficionado, sniped a toy cash register from the property. An electrician took fishing gear. The excavator who blessed the home took a pie tin with crimped edges. Strangers took taxidermied deer heads, old records, and rolling pins.

These histories belong to no one indefinitely and everyone downstream. As a tribute to those who have passed through, my dad preserves original wide-plank floors, ceiling beams, and stonework; clues hidden in plain sight. Then, beneath a piece of flooring or inside a basement crawlspace, he tucks away a few letters and photographs and newspaper clippings, to remain hidden until it’s someone else’s turn to decide. The looping cursive and unsmiling faces will be forgotten and discovered once more, drifting further out from their origin, a steady current into obsolescence or the public domain.

∾

Abbey Cahill is a writer living in San Francisco. She holds a B.A. in English with a concentration in creative nonfiction from Dartmouth College. You can find more of her work — profiles on truck drivers and dam-removers, diary entries, and musings on the relationship between memory & place — at abbeycahill.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.