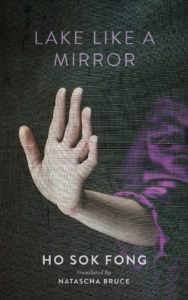

[Two Lines Press; 2020]

Tr. from the Chinese by Natascha Bruce

The nine stories in Ho Sok Fong’s collection Lake Like a Mirror are about women who drift in and out of zones where loneliness turns into isolation, where isolation turns into detachment, where detachment causes disappearance, and disappearance comes back again as some ghostly reincarnation to inaugurate the next generation into the modes of oppression. “Drift” might be the wrong word though. It might be rather “slip.” Gloomy circumstances do drift and fluctuate like our weather in its acute crisis and within those, the women slip. Ho Sok Fong makes us slip with them. Or do we simply relate? As some of these women lose track of time and cross the boundaries of what an ambiguous “body of we” calls “our shared reality” Ho Sok Fong switches narrators. Or not? Is it still the narrator observing the same character? Did a character turn into another character or the character into the reader? Did her body shape-shift into someone else’s shadow? We go back in the story. We read again. We reaffirm and slip again. And with every reading we understand a bit better. There is some work involved when reality drifts into another dimension, anxiety, but also moments of pleasure and joy. It does not just happen on its own. A structure makes it happen. Ho Sok Fong employs a structure in her writing. For her characters a structure exists in all the ways oppression takes a hold of a person.

In her 2003 article “Five Faces of Oppression” Iris Marion Young defined five different types of oppression: violence, exploitation, marginalization, powerlessness, and cultural imperialism. But no matter what definition you use she states, “oppression is when people reduce the potential for other people to be fully human. In other words, oppression is when people make other people less human.”

Less human. How can a human be less human?

The first story in Lake like a Mirror, called “The Wall” describes how a wall is quickly built in front of the house of an elderly auntie in response to a young girl running into traffic on the nearby highway and getting killed. The new highway protection wall causes things to deteriorate quickly for some of those behind it. No light gets into the auntie’s kitchen anymore. The auntie stops reading the newspaper. Because of the wall the backdoor does not open fully anymore and the backyard is reduced to the space of a toilet stall. The husband does not notice or care, he is fully immersed watching football games on TV. The auntie starts sleeping in the kitchen on a mat. She gets thin. One day a cat appears. The auntie grows close to a cat. “She hugged it close, feeling its weight against her, like the weight of the loneliness in the pit of the stomach.” The auntie, so thin she is almost see through now, starts walking through the narrow alleyway between the wall and the back of the houses. “She hadn’t expected that it would accumulate so much litter in so little time.” How does she react while walking through the garbage? “She couldn’t bear the thought of the cat picking through all this trash.” How about herself walking through the trash? Why can she bear that? Ultimately she can’t. She is eaten by a plant. She disappears. Yet not fully. She re-appears in the dreams of the children who live in the same row of houses. “Her complexion merged slowly into the gray of the wall and it seemed that the gloom all around us was her camouflage.”

What to say about a life dissolving into its own unfulfilled version like that? “The wind keeps blowing,” is one of Leslie Cheung’s most famous songs. I think of it, because there is lots of wind in the stories of Ho Sok Fong and a lot of rain. Most of her characters are very aware of the rain and the wind. Maybe it’s because only the rain and the wind still have the power to change something about an otherwise unchangeable situation. I think of it, because the last two sentences Leslie Cheung wrote into his suicide note before he leaped from the 24th floor of the Mandarin Hotel in Hong Kong on April 1, 2003 are translated like this: “In my life I have done nothing bad. Why does it have to be like this?”

Why does it have to be like this?

Most of Ho Sok Fong’s characters do not ponder “why” or recall “how.” They don’t kill themselves over these questions. They get their get their hair done. They paint their fingernails. They put eyeliner on. Their toenails are red. They sing love songs. They get bored out of their minds. They go crazy. They go quietly mad for not being given a chance to be who they might be in less suffocating circumstances. “When they could not say what they wanted, they loudly sipped their coffee. They talked a little about everything, but ultimately said nothing at all.”

Why does it have to be like this?

Patriarchy. Rapid Urbanization. Theocratic Government, a narrow version of Allah’s will brutally enforced by righteous people convinced that there is only one way to be human. When I told my friend about Ho Sok Fong’s story “Aminah” that takes place in a Malaysian religious rehabilitation camp she listened, and she nodded. When I had finished she said: “terrible,” and after a while of silence she added: “I am sorry you are being introduced to Quran this way.” And then she gave me her version of an introduction to the Quran and her religious practice. It was a sunny morning in Queens and it made me happy looking at her eyes lighting up, matching the sun rising over those elevated, gray, crumbling subway tracks across from us, as she spoke.

Most of Ho Sok Fong’s stories take place in Malaysia. Islam is central to and dominant in Malay culture. The story called “Aminah” starts with this note:

By law, all ethnic Malays, including mixed-raced Malays, must be Muslim. Applications to leave Islam are heard by the Syariah Court. Procedures vary according to state, but such applications are rarely successful.

A young woman has ended up in a rehabilitation center because she was wild and unruly and hated Islam. She applied to leave Islam but her request was denied. They assigned her the name Aminah, “the loyal one.” Somewhere in the wilderness, in a camp surrounded by barbed wired fences, she needs to learn that “There is no hiding from God.”

I try to imagine the place I want to go, once I am out. What I hoped for, a long, long time ago. No ustaz, no warden, no on claiming to have my best interest at heart. I want to go far, far away and be reborn, like a child. I want to give birth to myself.

First she rebels, curses, cries, then she stops talking, curls up on her bed, eventually she starts sleep-walking. She does this naked, which shakes up the warden, because it’s like a proof of failing Allah, and it’s confusing to the young, well-meaning male teacher Hamid, because it’s erotic and arousing and, somewhere “deep in the undergrowth,” relatable and familiar. And it’s strange or scary to the other incarcerated women and the men who have been, like Aminah, judged guilty of “licentiousness, deviant ideology, gender confusion, apostacy and forced into studenthood.”

A naked women covered by tiny scars wandering the compound at night under the moonlight.

The tales grew more fantastical with each retelling. In the kitchen, the cleaning lady and a huddle of students whispered about the sleepwalker’s supernatural ability to free herself from constraints.

Where is the unbearable cruelty in all of this? The young promising teacher Hamid meant well. He had tried to be reasonable, he was patient and restrained himself, kind, cordial, he had always looked for a solution, but at some point he “felt his interest waning, and slipped wordlessly away.”

It’s not necessarily monsters that hollow out a human’s core and destroy a soul, Hannah Arendt explained in “The Banality of Evil.” It’s a relentless routine and the fatalistic mindset of a hard working believer, a resistance towards thinking for oneself or others, a sickening sadness for those who can’t be “rescued,” despite all efforts to convert them.

I needed to read each story in Ho Sok Fong’s collection several times. I wasn’t able to fully follow some of the storylines immediately, I was a bit confused here and there, also a bit underwhelmed with not too much happening, a bit overwhelmed with the metaphorical descriptions of the emotional lives of her characters. Ho Sok Fong didn’t turn the oppression of her female characters into a thrilling adventure. The business of dehumanizing people and pushing them off the part of the earth that can be shared with other humans, is mostly the pretty mundane list of small actions and gestures, applied day after day after day after day. One small thing after another, scraping out her guts until humanity waves goodbye and leaves behind some scattered empty shells, mostly invisible, were it not for their gloomy shadows that slowly grow on all of us who are still here.

This post may contain affiliate links.