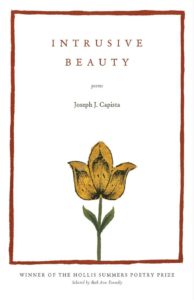

[Ohio University Press; 2019]

In many ways, the themes and underlying concerns in Joseph J. Capista’s debut collection Intrusive Beauty hearken to the works of poets such Robert Frost, Wallace Stevens, Donald Justice, and Stephen Dunn, all of whom have been at varying points categorized as male domestic poets — lyricists writing about home life who also often grapple with changing conceptions of masculinity in changing times. As the middle-aged speaker in Intrusive Beauty takes stock of his life’s direction, changing roles, and lessons, he also illuminates transformed notions of the heterosexual American male, particularly as they are complicated by the vocation of poetry writing, a practice traditionally characterized as a “feminine.” Capista’s volume presents necessary reading not just for the exquisite lyricism and musicality its poems evoke, but also in the way it can be seen to function as cultural evidence and barometer on changing views of masculinity in our information age-society that has launched the #MeToo movement amid hypermasculine Trumpism.

Little known poetry about the challenges of domestic life written by male poets appears to exist prior to the twentieth century, certainly in stark contrast to the works of female poets. The culturally-enforced gendered distinction between the private sphere of the home as a “feminine” realm and the public space outside the home as a “masculine” realm seems to prevail in the works of earlier male domestic poets, as seen through the ways in which their writings exhibit an ambivalence and even anxiety about their social and cultural positionality as men writing about home life. Complicating this ambivalence and anxiety was the literary context in which they wrote, which espoused a “masculine” modernist aesthetic promulgated by the likes of Hemmingway, setting itself in contrast to stereotypes of poetry writing as soft, emotion-driven, feminine, and therefore, culturally at odds with notions of masculinity and male work. As a result, Frost, Stevens, Justice, and Dunn, as male poets writing about the domestic, often seemed compelled to characterize their work as a kind of enlivening force to counter what was portrayed as the complacency and relative inaction of domestic life and to resist the conflation of their work with the feminine.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of Capista’s work is how much it exhibits an inheritance from these earlier domestic male poets through similar explorations of middle-aged anxieties, which, however, are totally removed fromassumptions of Western male hegemony whose dichotomization of the masculine and feminine espouses male dominance and superiority over females. In other words, although the ostensible topics and themes explored by the speaker(s) of Capista’s poetry may overlap with those of earlier domestic male poets, they are freed from any implied gendered notions or assignations, notably signaling an ideological departure from Western male hegemony.

Like the work of earlier male domestic poets, Capista’s centers upon concerns faced by many a middle-age man today: fatherhood, marriage, home, work, and material security, to name a few. The influence of the earlier poets on Capista at times seems undeniable in lines such as those from “Thirtysomething Blues” where Capista’s speaker, like the speaker in Donald Justice’s famous “Men at Forty,” whose bittersweet acceptance of adulthood and the dreams of youth sacrificed to attain material comfort and “mortgaged houses,” similarly bemoans:

The job, car loan, the mortgage on the house:

the things we need are things, not dreams but plans.

Capista’s Baltimore poems such as “Sowebo” and “Guide to the Monumental City” are also reminiscent of William Carlos Williams’ New Jersey poems and insistence upon localized focalization. There is also the ubiquity of birds in Capita’s poems such as “Telescope,” “A Child Bird-Scarer,” “Migration Theory,” “Entreaty,” and “The American Crow and the Common Raven” reminiscent of the birds that often signal transcendent experiences in Wallace Stevens’ poetry. And last but not least, Capista’s seemingly autobiographical explorations into the ways in which the roles of father and poet interact also recall Dunn’s work.

Despite the continued existence of certain tropes of the male domestic poet in Intrusive Beauty, no assertion of stereotypical hegemonic masculine traits is ever privileged, implied, or assumed in Capista’s hands, nor is any of the anxiety exhibited by the poems connected to any fear of conflation between gender roles or distinctions. For Capista’s speaker, who in fact even names Emily Dickinson as a literary forebear in “For a Daughter,” the worry over retaining masculine dominance never comes up and seems completely out of the purview of the speaker’s concerns. What we have instead are representations of male thoughts and feelings that counter male stereotypes.

Take, for example, the poem “Thaw” where during a winter drive home, a married couple learns about the frequently too-late discovery of human fatalities caused by roadway ice. The opening lines of the poem paradoxically depict the delicate precariousness ever threatening to implode at the center of life’s otherwise predictable cyclicality:

All afternoon police unearth

the dead from the roadside drifts of snow.

It happens like this every spring:

a passing motorist reports

dark tint inside a melting pile

or catches sunlight glinting off

a well-sewn button or a shoe.

Perhaps a hand, a bud unbloomed,

extends there toward imagined help.

Found are those whose orbit slipped

some imperceptible degree

before we ever thought them lost.

We watched a drifted stagger through

three lanes of traffic, arms asway

as if conducting some rush hour

motet his ears alone could hear.

He waved. I almost waved right back.

In lilac light the cruisers flashed

against the dusk . . .

Although we are told that “It happens like this every spring,” the speaker nonetheless makes the reader take pause for the uncommon observation that silently follows passing glimpses of small, inconspicuous objects — sunlight, button, shoe, a bud unbloomed — in effect, de-familiarizing what is normally ignored or taken for granted. In doing so, the lines create a sense of heightened observation and awareness that accompany the welling of spousal anxiety we have seen in the traditional male domestic poets’ work. But while Dunn and Wallace might have brandished their writing practices as ways to assess and cope with unknowns, Capista seems to largely forgo an assertion of control, and in its place, relinquishes his circumstances to the currents of chance. “Foam lifts me, holds me, sings me back toward shore,” as the speaker’s chorus in “The Beautiful Things of the Earth Become More Dear as They Elude Pursuit” describes. And indeed, the scarce insistence upon control and dominance inherent in the poems’ frequent surrender to chance outcomes and endangerments, or, what can also be seen as their renunciation of obligatory performances of mastery and self-mastery that underpin patriarchally-defined conceptions of manhood, is where evidence of Capista’s reconstructed masculinity mostly lies. Whether speaking about his experiences as father (“40”), husband (“Cornicello”), or friend (“Exit Wound”), the relational interpersonal dynamics assumed or espoused by Capista’s speaker(s) is one of equitable partnership and interchanging roles, in clear contradistinction to gendered prescriptions behind the Western hegemonic notions of men as emotionally self-sufficient-providers and protectors, and women being the primary nurturers responsible for raising children and supporting men.

The lines of “Thaw” proceed to describe the jarred reactions of the

married couple to the human fatality discoveries:

. . . Someone dug.

Someone else rerouted cars.

We drove directly home to lie

together side by side, converse

about these newly exhumed dead.

You fear, I know, our daughter woke

mid-fight to hear about our own

dissolving dreams, this falling out of,

into love. The dead are neutral ground

and so, exhausted, spent, to them

we steer our words. It's almost prayer.

Tonight they'll rise from deep inside

of me as, half-asleep, I turn

and slip my hand in yours. But first,

so that my touch won't startle you,

won't wake you from unquiet dreams,

I'll hold my hand out to the night

and let it grow a little cold.

As the lines above gesture toward parallels between the witnessed destruction of human life and the couple’s latent relationship troubles, no differentiation is made between the roles and responsibilities between husband and wife. In place of exhibiting traits associated with traditional masculinity such as toughness, power, independence, emotional restraint, and competitiveness, we witness a speaker who, in communicating directly and openly with his wife in the poem’s lines, exhibits a traditionally female-ascribed emotional vulnerability free from any traditionally male-ascribed affectation of stoic, emotionally-suppressed self-reliance.

The second section of the book, whose poems document the speaker’s experiences working at youth shelter homes, continue to upend traditional gender roles without any trace of irony. Here the speaker takes on child-rearing duties as de facto primary nurturer to abused or criminalized kids. The speaker prepares their meals (“Gut Bomb”), teaches their classes (“Johnny Salmon’s Father Enters the Shelter Unannounced to Repo His Adjudicated Son”), and takes them to fun day outings (“Vigilante Day Parade”). Given how work is greatly coterminous with masculine identity in Western patriarchal societies, and how men are often judged based on the nature of their professions and amount of compensation they receive, it is notable that the second section of the three-part volume which undermines the sexist view of child-reading as exclusively woman’s work, is at the very center, at the heart of the book, so to speak.

While most of the poems in Intrusive Beauty signal considerable departure from Western male hegemonic assumptions, Capista’s work is not, however, completely dislodged from certain branches of their pervasive reach. In “Playboy’s Guide to Lingering,” for example, quoted in full below, we can see an enactment of peer group socialization and “masculinization” deploying the playboy script that urges male sexual aggressiveness, promiscuity, and conquest as provisionary requirements of indoctrination into full-fledged manhood:

We read lingerie as lingering

An innocent mistake, yes, though

we didn't dally in Patel's humid

newsstand amid hands of cigared

tobacco and men in coveralls logger-

heading with the Pennsylvania Lotto

to expand our budding tongues,

but to confuse the single shelf

of cryptograms and crosswords

with the candied shelves of pornos.

Despite our lousy decoding we proved

adept disrobers, kid-minds keen

to peel from skin what we'd later

call satin the way we peeled glossy

clementines slipped in our stockings,

our reward for a year of skirting Satan.

Nonchalant as bubble gum, we thumbed

them cover to cover, lingered, elbowed

on another, dittoed each sweet

image deep in memory's folds:

love's coy postures, saddle-stitched.

And that is how we imagined

it would be for us on those winter

afternoons: flimsy resistance, finger's

steady pressure, split of soft fruit.

We'd puzzle over language later:

For now, we had on our hands

more important things to misread.

The boys’ surreptitious perusal of porn magazines captures how expectations of male aggressiveness and conquest of the female objectified body frequently necessitate the practice of risk taking and recalcitrant behavior as part and parcel of men’s sexual education and training. While still largely innocent, as punctuated by use of vocabularies of uncertainty (“mistake,” “confuse,” “lousy decoding,” “puzzle”), the boys’ curiosity can attest to the ubiquitous pressure imposed upon males in Western society to conform to masculinist mores. As the boys stare at one-dimensional images of women, they become “adept disrobers,” and “imagine” flimsy resistance, unknowingly affirming the patriarchal preference for subservient, ready females. But as the poem is written in hindsight, from the vantage point of the now-grown male poet, it interestingly ends with the word “misread,” suggesting an authorial opinion that runs wholly counter to what had previously been presumed or thought. Here then would be concrete instance of Capista reflecting critically on toxic masculinist socialization, and its resulting assumptions and beliefs.

Furthermore, “Playboy’s Guide to Lingering” also hints at the destructive consequences of indoctrination into a male hegemonic system that promotes sex without emotional intimacy as the primary way for men to connect, and sexual conquest as the primary way through which men measure themselves. The reference to “budding tongues” that is recalled later by a similarly organic reference to “soft fruit” ties together linguistic knowledge with sexual knowledge, with the former subordinated to the latter. In this way, the grown poet suggests how the skewed priorities of patriarchal socialization can endanger true individual self-realization and determination, just as the poet’s younger self recalled in the poem casts aside attempts at verbal precision and accuracy (“we’d puzzle over language later”) in favor of sexual discovery and prowess.

Finally, it is notable that the views in Intrusive Beauty, which undermine Western male hegemony’s gender dichotomization and male dominance, are not presented as active or deliberate acts of subversion, but as accepted norm. It is as if the speaker’s attitude and world view has so evolved and spread among his audience such that there no longer is a need for a purposefully pointed and political approach in overturning traditional gender expectations. What we witness instead as readers of Capista’s poems are repeated enactments of empathy and emotional sensitivity, something that the #MeToo movement has vociferously encouraged men to undertake through therapeutic exploration. The very lack of ambivalence in the speaker toward the reconstituted masculinity he forwards, which unquestioningly portrays equitable relationships and interchanging roles, evidences how already deeply embedded assumptions and ideals of gender equality are in the poems’ lines, signaling a most hopeful and welcome sign of progress.

Abigail Licad has loved poetry and dogs since childhood. So it quite follows that she now works as a corporate paralegal at a Silicon Valley tech company.

This post may contain affiliate links.