Three weeks into my first semester in Columbia’s mfa program, I sat in a packed classroom and listened to Richard Locke lecture 65 students on the merits of Virginia Woolf’s The Common Reader. Locke’s lectures were carefully crafted presentations that showcased his insight and erudition, plunging the classroom into a placid silence for two hours. At the end, he asked if there were any questions, and a brave young man from the back of the classroom asked/shouted, “What is the point of these mfa programs?”

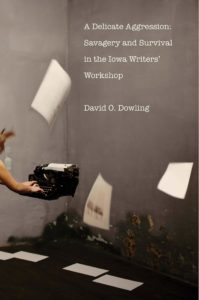

It’s a reasonable question. Each year, around 20,000 applications go out to over 200 creative writing mfa programs, each promising a version of success that involves lucrative book deals, publication in prestigious literary magazines, and the relatively modest fame and fortune of someone like George Saunders. All this despite a devil’s bargain in which the top programs are tuition-free (with a meager stipend for teaching undergrads) but have acceptance rates hovering below one percent while less exclusive programs charge exorbitant tuition fees despite a powerball’s chance of future financial security. At the very top of this pyramid scheme is the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, the University of Iowa’s graduate program for fiction and poetry and the subject of David O. Dowling’s latest book, A Delicate Aggression: Savagery and Survival in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

As a murmur of shock skittered around the classroom that day, Richard Locke answered the question calmly: Imagine you’re a young writer in 1922 and you want to go be a part of the lost generation in Paris. You want to meet Hemingway and Fitzgerald and get your novel read by Gertrude Stein. So you go to Paris and frequent the cafes and bars where they’re rumored to hang out, hoping to catch a glimpse and gin up the courage to introduce yourself to them. They love your work and agree that you can be part of the club. Well, the mfa is the 21st century version of that.

That settles it: these programs are havens, creative safe spaces where young writers can spend valuable time finding their voice and networking with other writers. But what about those cynical, unpublished grads who claim that the mfa is a scam that uses underfunded and overworked students to provide revenue and labor for the university’s bottom line. Or what about me, the cynical working class kid who thought the elite programs were an indulgent pastime for rich kids who feel their creative impulses hampered by the worlds of business or charity? Or that undergrad professor who told me that less-esteemed programs were training camps for adjunct jobs in flyover states?

In Delicate Aggression, Dowling goes back to the original source waters of the mfa boom to posit that creative writing mfa programs were originally designed as a professionalization tool in which talented young writers were to be shaped into publishing industry cogs, churning out good, popular prose for the post-war American public. According to Dowling, this idea originated with Paul Engle, director of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop from 1941-1965. Dowling frames Engle’s philosophy of professionalization as a rebellion against the mysticism of his Methodist upbringing. He hated the idea that authors were creatively inspired in the same epiphanic manner that Methodist preachers were called to divine service (what worked for Saul of Tarsus on the road to Damascus shouldn’t work for Saul of Quebec on the road to Chicago). So Engle used the “obscure” classroom methods Wilbur Schramm, the actual founder of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, to turn the program into a mid-century literary professionalization factory, the Fuller Theological Seminary of the written word.

Dowling doesn’t seem very interested in Schramm or those originary classroom methods, instead spending nearly half of Delicate Aggression exploring Engle’s twenty-four year tenure as director and even calling the program Paul Ingle’s Iowa Writers Workshop in an early version of the subtitle. Dowling justifies this interest in Engle, painting him as a Gatsbian figure who left his birthplace in Cedar Rapids to study at Columbia and Oxford before returning home to bring high literary culture to the Midwest whereas Schramm comes off like a stone best left unturned.

After all, it was Engle who made Iowa City a literary destination by being fanatically dedicated to the commercialization of craft. Like a literary P.T. Barnum, he recruited the best writers of the day to teach the best writers of the future while he traveled the world and begged for money, fellowships, and grants from anyone who would listen. A fake-it-till-you-make-it snake oil salesman, he created the prestige of the program out of whole cloth by saying it loud and often enough until it became true.

This parallel set of ideas — the mfa as a vocational program for wordsmiths and Engle as a self-prophesying carnival barker — is an intriguing one that threads through the work to guide the narrative along. Unfortunately, instead of maintaining this focus on Engle, Dowling, who — it should be noted — is an associate professor at the Univeristy of Iowa’s journalism school, sets out to tell the full, definitive tale of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop™.

After a gauntlet-throwing introduction, he structures the book as a series of critical biographies covering some of the more famous and influential of the workshop’s alumni and faculty. What we end up with is a stilted series of episodic chapters that don’t quite tell the story of the program and don’t do justice to the individual writers that are profiled.

Perhaps the most famous person ever associated with the workshop, Flannery O’Connor is given a drive-by treatment wherein we are told a few delicious pieces of information about her time at the workshop alongside more tales of Engle’s hucksterism. Dowling attempts to tell the story of the workshop and the story of O’Connor’s auspicious beginnings but somehow does neither.

This occurs throughout the work. Most of the reading experience is spent bogged down with granular detail about fringe Iowa figures or compare/contrasting that detail to Engle’s original vision for the program.

I came away from this book wishing that Dowling had just written a biography about Paul Engle since that seems to be what he’s most interested in. When he’s writing about Engle, the prose and ideas come alive in a unique and interesting way. One anecdote has Engle engaged in the rigorous examination of a workshop student’s poetry when he stops class to take a lengthy phone call. Some time later, he re-enters the classroom like a conquering hero and proudly announces “The National Gas Fellowship in Creative Writing!” before diving right back into the student’s work. Amazingly, his Gatsby comparison doesn’t feel strained. Engle leaps off the page as one in a long line of uniquely American bullshitters, a unique blend of Don Draper, Charles Foster Kane, and Philip Seymour Hoffman’s L. Ron Hubbard impression in The Master.

The further the text gets from Engle, the more disinterested Dowling seems. He lets his impeccable, back-breaking research guide the prose instead of vice-versa, leading to a wikipedian style which isn’t helped by the copious number of endnotes. There is also a thread alluded to in the title that focuses on the savagery of the workshop experience itself. Although Dowling opens the book with a fistfight, this thread of workshop warfare peters out, unexamined. The reader is periodically reminded that sometimes people are mean to each other as part of the workshop and then other threads are given more time and ink.

The book doesn’t succeed as a pop-history book for the curious bibliophile (or mfa student/hopeful) precisely because it doesn’t seem interested in telling the chronological meat-and-potatoes history of the program. Stuart Jeffries’ Grand Hotel Abyss: The Lives of the Frankfurt School is a recent high-water mark of this genre which works precisely because of its simplistic, single-minded narrative thread that is divided into broad sections such as “The 1920s” “The 1930s,” and “The 1940s.” Instead, Dowling is playing the game on hard mode, trying to wed the depth and digression of critical biography to the broad narrative of institutional history, producing a handful of fascinating loose threads as opposed to the singular vision that the book imagines itself to be.

What leaves the most lasting impression is Dowling’s portrait of Paul Engle and the implications of his original vision for the program. After all, despite the many ways in which these programs (both Iowa and Lesser) market themselves, the true fact undergirding this entire topic is that these programs are still largely concerned with Engle’s original vision: hiring the best teachers they can afford (typically defined as “most published”), to teach the most talented students they can get, so that those students will publish far and wide and gain the type of literary renown to either put the program on the map or add to its already established status. In short, these programs are professionalization machines in much the same way as business or medical schools, but the market is far less kind their graduates. Dowling is uncritical and unsentimental in his portrayal of the mfa as the death-knell of creative solitude, spontaneous community-making, and writing for writing’s sake. In its place, the mfa transformed literature into something amenable to the cultural logic of late capitalism. Ultimately, it is this idea that resonates most strongly for anyone interested in the mfa boom and its implications.

In a moving epilogue, Dowling reminds us that Engle is no longer clearly associated with the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. He has no name on any building, fellowship, or hallway. It is a sobering message for the prospective, current, or future mfa student. In an age when ivory towers are run like corporations, if you aren’t adding value to the program’s bottom line, there’s no more room in the inn.

Jacob Carroll is a Nonfiction Writing MFA candidate at Columbia University. He is currently at work on a memoir project about family, religion, and class in the deep south.

This post may contain affiliate links.