Stephen Furlong: If you could pinpoint a timeframe or a life experience that you could call your poetry origin story, what would it be? Who are your poetic inspirations?

Emma Bolden: I remember the moment I felt called to poetry exactly: second grade, Miss Hanks’ class. I was terribly bored. I flipped through my English textbook, which was what I did when I got bored. In the supplemental section in the back of the book, I found Emily Dickinson’s “I’m Nobody! Who Are You?” Dickinson herself wrote that “[i]f I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry.” That’s exactly how I felt in that moment. I was tremendously awkward and tremendously nerdy and also tremendously unpopular, and then I found this poem that not only described how I felt every day but celebrated it. I’d always loved to write, but in that moment, my feelings about writing transcended even love: I knew it was the thing to which I was going to – I had to – devote my life.

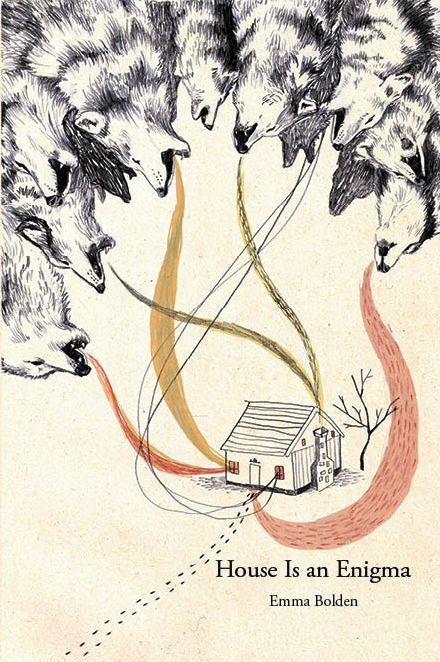

Needless to say, Dickinson is one of my biggest influences. Other influences include Anne Carson, Robert Creeley, Louise Glück, Laura Jensen (House Is an Enigma takes its name from one of her poems), Kate Knapp Johnson, Claudia Rankine, Adrienne Rich – I could probably continue this section for days, to be honest …

One of the early poems of yours I remember reading was “Every Tale About Hunger” from Fairy Tale Review and I’m still struck by the following lines:

“…When he has a vision of home, he has

a vision of walls. When she has a vision of home,

she builds another wall.”

While writing is a soloistic activity, I believe it thrives in community. How has your community grown and developed while being outside academia?

I must admit that it’s been difficult; however, I must also admit that that difficulty is largely (perhaps entirely) of my own making. I left academia in 2015. It was the best thing to do for myself. It was the only thing I could do for myself, and it saved me. That didn’t make it any easier. I started studying creative writing at an arts school when I was in 8th grade. I grew up, in a way, with the assumption that academia was the only path forward for a writer, and I believed that deeply. It was an amazing experience, in so many ways: I loved teaching, and I treasured the time I spent in the classroom and with my students. I will always be grateful to them and in ways that I can’t fully articulate. They taught me far more than I ever could’ve taught them. Academia and I, however, were not a good match, and I was dangerously unhappy. When I left, I admit that I felt ashamed, as though I’d let all of the people who’d cared for and taught me down, as though I’d betrayed them by walking away from what I had been taught was the only way. That kept me (read: I kept myself) from reaching out to writers in my community for a long time. When I left academia, I assumed a thousand doors would close. While some doors did, others opened, and brought with them new ways of speaking and thinking about writing and living as a writer. Thankfully, by some great grace, I ended up moving back to my hometown near Birmingham, Alabama, a place with a vibrant, vital, exciting, and accepting literary community. Just knowing these luminous human beings has changed my life as a writer and as a human. They’ve taught me there is not one way, and that shame is the last thing I should feel about taking a path I had to take to save my own life.

You currently serve as the associate editor-in-chief at Tupelo Quarterly, how does writing inform your editing? How does editing inform your writing?

Working as an editor has given me a great deal of respect for the often-arduous act of putting a literary magazine together. As a submitter, it’s sometimes easy to forget that on the other side of Submittable sit human beings, just like you. Being an editor has taught me to remember that, when it comes to submitting. It’s also taught me that a rejection doesn’t necessarily mean that the poem is bad – there are so many other reasons that a piece may not be a fit at that time. Editing is a life-giving thing when it comes to writing itself. There’s something awe-inspiring about opening up your queue and seeing all of the different voices there, all of the people who love this strange and beautiful thing that we do with words. I carry that awe with me when I turn to my own blank page.

You won a 2017 National Endowment for the Arts (congratulations and more congratulations!), why are fellowships and artistic funding opportunities important? How did that sort of recognition help you produce more work and not feel overwhelmed by the pressure?

I’ve often said that my NEA fellowship was a life-saving gift. I mean that literally. When I got that call, I was at the lowest point in my life, both personally and professionally. I wasn’t even going to apply for the grant, at first: it was the sixth time I’d applied for poetry, the eighth time I’d applied overall. I put the application together at nearly the last minute and then put the hope of getting a grant aside. The funding was vitally important, yes, but more than that, just knowing that the panel had this kind of faith in my work helped me return to having faith in my work. This faith allowed me to push myself, to take risks, to take my work into places that didn’t necessarily feel comfortable but absolutely felt necessary. The scope of my work widened, and I soon found myself engaging more widely – and wildly – with the world on the page. It’s a gift that saved my work and my life, and for which I will always be grateful.

I find it incredibly admirable that you write across a multitude of genres, is there a specific way you recognize when something is going to come out an essay, poem, or story?

I studied creative writing at an arts school from 8th – 12th grade, and one of the reasons I’m so incredibly grateful for that opportunity is that we studied multiple genres: generally, poetry in the fall and fiction in the spring, though I also studied creative nonfiction and playwriting while I was there. It’s been quite a long time since I was in high school, but I still find myself clicking into that genre switch in January. I focused entirely on poetry for a long time after high school, and only began to write creative nonfiction seriously when I was 28. At first, it was difficult to tell whether a line or an idea wanted to be a poem or an essay. In fact, a lot of my work from that time period blurs genres; it always seemed to want to live in the liminal spaces in between. As I’ve gotten older, my ideas seem much clearer about what they want to be, whether in one definite genre or somewhere in between. There’s a certain kind of energy I’ve learned to recognize, something different about the ways words arrive when they want to be prose or poetry.

House is An Enigma—when I say that title aloud, what emotions come up for you?

Pride. A lot of pride. The poems in this book are my most personal and most frightening, as they address the things that frighten me the most. I wrote most of the poems in the collection after I had a total hysterectomy and oophorectomy at 33. I knew this surgery was inevitable, but I wasn’t prepared for the utter confusion and gut-wrenching emotion that came along with the surgery. I was also raised in the Deep South, and this fell under the category of things you just don’t talk about. Through these poems, I found a way to access, express, and sometimes even understand the emotions I went through. I also found a way to move past shame and into speaking up and out and even, at times, loudly about the way I experience living in a female body and struggling with reproductive health problems in a society that so often seems outright hostile to women and their bodies. I still feel the echo of shame and confusion, but I also feel the clarity and peace that comes with speaking out about these difficult things.

You employ prose poems, couplets, tercets, and a multitude of other poetic vehicles, when do you recognize a poem is starting to take shape? On a larger scale, House is broken down into five sections, how did that come to be?

Helping a poem find its shape is one of the most difficult tasks in the writing life, for me. I tend to draft by hand in hurried, clunky prose blocks, sometimes with occasional backslashes to show where a line break might like to be. I then type up the drafts and begin the difficult task of crafting this brain-dump material into something that might make sense enough for other people to read. It’s a bit like sculpture: chipping away at a solid block until I find the shape underneath.

When it comes to shaping a manuscript, I have a similar process. In graduate school, my thesis director, Mark Cox, taught me the method of assembly I still use today. I print out all of the poems that feel ready and part of the same manuscript and put the print-outs on the floor. I spend a while walking around them, trying to pick up on images, moods, and narrative themes. Then, I start looking for similarities and move the poems around. I think of revising individual poems in terms of sculpture; I think of ordering a manuscript in terms of composing. I tend to look at each section of a book as a musical movement developing a particular theme. I shape them in terms of rise and fall, variation and completion. I think that my first version of House had three sections, but as the years passed (I put together that first version a long while ago, perhaps in late 2013), the movements and themes became more complex. There was a shift in the narrative aspect of the manuscript as well. At first, I had a tremendously difficult time writing openly about having a hysterectomy (which happened in early 2013). I envisioned the book as a series of poems that ended in the big reveal that I’d been writing about my surgery. When I worked up the bravery to be more open, I realized that this big reveal wasn’t doing anything much for the work, and that this cloud of mystery over my body wasn’t helping my work or me or anything. Once I had that breakthrough, I was able to write much more openly and specifically, and the book’s shape shifted into five parts to be able to handle more complexity.

Your book House is An Enigma is almost a year old now, which I still cannot believe, but how does that you feel? How has reading from it developed over the course of having it out in the wild more?

It’s an amazing feeling to have this book out in the world. It’s affected me deeply and personally. Before, I felt like I walked around with this enormous strange secret: the fact that I couldn’t have children and I’d had a hysterectomy. At the same time, I felt guilty for feeling like this was something I had to keep secret and couldn’t discuss openly. House put that information out there, and in a lot of ways, that set me free. The poems have also given me a way to speak out about my experience with reproductive medicine and how damaging it is for women to feel like what happens inside of and to their bodies is somehow shameful at all, much less so shameful that it requires secrecy.

There are a couple of poems in House (“For the Doctor Who Suggested I Try to Explain How It Feels to be Barren”, “The Cities We Love Are the Ones That Are Drowning”) that demand the reader to physically move the book to read them, how did that come to be?

It actually came about accidentally. I have a bad habit of writing the same types of poems about the same things over and over again. When I realize I’m writing myself into a circle like that, I’ll do something to break myself of it by changing the process of writing. Since I write by hand, I’ll sometimes turn the notebooks so that I’m writing longer lines in a physically larger space. One of those poems, “The Cities We Love Are the Ones That Are Drowning,” was accepted by The Pinch. The editors were amazing and came up with the idea of printing the poem sideways. There’s something about having to turn the page that connects the mind to language differently – it’s a feeling I loved when reading Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves, and one I’m glad made its way into the final book.

I don’t want to single out any one poem, but a personal favorite from House is “X”, would you mind talking about that poem, as you see it?

“X” is actually one of the oldest poems in the manuscript. I was nearing the end of a NaPoWriMo poem-a-day project and I was desperately running out of inspiration. I had a conversation with the (absolutely incredible) departmental secretaries at the school where I was, at that time, teaching. One had been an x-ray technologist and told the story of how the X-ray was invented, which became the core of the poem. At the time, I was going through test after test for neurological symptoms; they never really seemed to get me closer to an answer, but the idea of an answer being there in the body, visible only by machines, haunted me.

I admit, I’m not a huge fan of the question what are you working on, instead (if you’d like), feel free to use this platform to talk about something you’ve recently found that deeply interests you and talk about it. If you don’t want to share anything, I will cut out this question.

I love this question! A while back, I came across Agnes Obel’s album Citizen of Glass, and I cannot get enough of it. It’s a concept album about mass surveillance, the internet, and privacy. The title comes from the German term “gläserner bürger,” or “glass citizen,” and the idea that we willingly let go of privacy and use our most personal experiences to create content on social media. By becoming transparent, we become fragile, and the ways in which Obel explores this idea are just astounding. I’m also obsessed with the way that she constructed the album itself, from voice modulation to layering hundreds of tracks on top of each other to her use of the trautonium, a synthesizer from the 1920s. I’m currently trying to make everyone I know listen to this album so that I can talk about it.

This post may contain affiliate links.