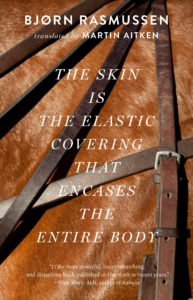

Tr. from the Danish by Martin Aitken

At one point in Bjørn Rasmussen’s The Skin is the Elastic Covering that Encases the Entire Body, published my Two Lines Press and elegantly translated by Martin Aitken, the narrator Bjørn self-operates on his body, giving it an extra hole in the soft area between penis and anus. In this raw and provocative novel, what’s more shocking than the act in itself is how tender it feels, so tender that calling it ‘mutilation’ feels wrong. This scene occupies an emotional space somewhere between repulsion and longing, a space perhaps unfamiliar in most of our lives, but one traversed consistently in this novel.

The heart of the story is Bjørn’s affair with an older, male riding instructor which started when Bjørn was only fifteen years old. Naturally, this relationship throws young Bjørn into a maelstrom of feeling. Shame, desire, love, hate, loneliness, depression. Our primary vista of this time is years afterward, when Bjørn is decidedly more stable and the affair has long burnt out. Like the best parts of Knausgaard’s My Struggle, Rasmussen achieves a blend of experience and analysis. Raw, teenage feelings are transliterated then digested. Rasmussen switches between third and first person, seemingly wantonly, suggesting Bjørn is now able to recognize the affair as trauma while still admitting it didn’t feel like trauma at the time.

Interspersed amongst the more conventionally narrated thread are young Bjorn’s letters to the riding instructor, pop songs, poetry, dips into another character who I can best surmise is Bjørn’s mother. The novel is slim, and as a result, these shifts feel more like wild careens than subtle turns. The Skin is dark, make no mistake, but the collage-like narrative overwhelms with the same intoxication of romance. There is little room to breathe, and the reader is more drawn by intuition than logic.

Fittingly, young Bjørn is drawn to the riding instructor in the same way. The instructor, who goes unnamed, is domineering. He issues sexual instructions to Bjørn and draws up a contract as their affair progresses. As expected, he also remains emotional distant in private and physically distant in public, only sneaking brief contacts, like strokes under tables. Bjørn, for his part, pines for the riding instructor badly, and the instructor’s cold behavior only serves to enamor Bjørn. His method of communicating desire is destruction: he threatens to expose the riding instructor as a pedophile, he slices his prized saddle. As Bjørn’s cries for love go unanswered, his anguish deepens.

While this is playing out in the text, we get glimpses of Bjørn’s past and future. After leaving home, and, consequentially, the riding instructor, he works in a brothel and is taken under the wings of a madame and a fellow, though female, sex worker. Bjørn isn’t happier in the brothel, and sex becomes a death-drive for him, a means of erasing suffering, something to binge. But why sex? Why not food? Or sports? Or horse riding? Or books?

His past seems to offer an answer to this question — why sex is Bjorn’s obsession, why it is the key to his identity and autonomy. Before his affair with the riding instructor, when Bjørn was ambiguously younger than fifteen, he begins sleeping in his mother’s bed after the family’s beloved dog was fatally shot by a hunter’s stray bullet. Ostensibly, the dog’s death is what led Bjørn’s mother to eventually molest him, just as that trauma was what led Bjørn into his affair with the riding instructor, just as that affair leads him to eventual employment in a brothel. But both Rasmussen and the deconstructed narrative are careful to not assign blame — there is an absence of explicit cause and effect, and with it, an absence of subject and object, consent and refusal. These elements exist, of course, but the frantic narration manages to obscure them, or at least deny them easy answers.

For example, I feel a little uneasy claiming Bjorn’s mother molested him. The way this information is relayed in the book is through an unattributed section of dialogue — Bjørn breezily claims he and his mother had sexual relations (this sounds stiff and academic, but it’s not exactly clear what happened). Likewise, Bjørn’s affair with the riding instructor stands as his first opportunity for happiness. Whenever bitterness and regret seeps into the text, it’s not so much because these things happened at all, but because they didn’t end in the way Bjørn wanted.

What is to be made of this, ethically? I’m not sure. I’ve haven’t gone through anything like Bjørn has, but I’m certain I wouldn’t like it if I had. But my certainty doesn’t mean I get to dictate Bjørn’s feelings, it doesn’t mean I get to draw a straight line from his early sexual experiences to the misery that pervades him, especially if that line in the novel is deliberately queered through narrative technique. Rasmussen asks us to consider questions of power, happiness, and fulfillment: who deserves it, who gets to have it?

The Skin makes these questions fascinating to consider, but nearly impossible to answer. Again, because of the shifting shape of the narrative, what is actually true and what actually happened is left up for debate, particularly in the sections with Bjørn and his mother. You could argue Bjørn did experience these things, or you could argue they are merely symbolic fever dreams. Both would be valid, though there is certain vulnerability in the narrative that has me inclined toward the former.

The question of narrative reality doesn’t end there. Of the three photos included in the book, one is a tree the riding instructor describes to Bjørn elsewhere in the text, and another is an old equestrian score sheet bearing Bjørn Rasmussen’s name.

Is The Skin autofiction? I’m not sure. Evidence, like that outlined above, is there. However, the question, feels more daring in The Skin than it does in, say, a Sebald novel, while also feeling more frivolous. In the end, any effort to connect the author to the narrator feels more like a distraction than anything else — the novel contemplates a truth beyond that of the easily conferred. Pain. Love. Shame. These emotions radiate from The Skin so powerfully, the narrator might as well share your own name.

There’s no English-language interview with Rasmussen to confirm or deny speculation, anyway. What we know about him is almost reserved to the publisher’s copy. The Skin was his debut novel, published when he was 28, and it won the European Union Prize for Literature. He was a playwright, a poet, and has published two other works of fiction since his debut.

Rasmussen is well-read, and the book is decidedly in conversation with a host of other authors listed near the end: The Skin is queer in the tradition of Acker, romantic in that of Duras, and lonely like Plath. But I didn’t find my mind reaching for critical companions while I was reading. The Skin is the Elastic Covering that Encases the Entire Body is a private and gem-like book, and reading it is unmediated access to a maelstrom. I was pulled by equal parts curiosity, repulsion, and empathy. Rasmussen has managed to stretch the soul in the way a butcher might stretch flesh, asking us to consider the roots of our desires and the depths of our longings.

Kyle Callert is a writer from Detroit. He is Assistant Fiction Editor at Ninth Letter.

This post may contain affiliate links.