Tr. from the Japanese by Sam Bett

For my 23rd birthday I was gifted a copy of The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea by the then future cosmic-country star Dougie Poole. Doug and I had taken an undergraduate creative writing class together, and Doug is a beautiful writer and a careful reader. The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea was the first Mishima book I had ever read. I was mesmerized by the book’s quiet violence and vivid, stark sentiments.

When I find an author who moves me greatly I usually buy a copy of everything they produced, and then I read through the author’s life work chronologically. This proved difficult with Mishima for several reasons. Despite Mishima’s short life, he was intensely prolific across a myriad of different mediums. He wrote over twenty novels, ten or more plays, and acted and directed in many films. He made so much that it is difficult for me to even find a precise and reliable accounting of what exactly he produced, and which works of his have been translated into English from the Japanese, and which works still remain to be translated.

Mishima was also an intense and serious body-builder, and did extensive modeling. While, on the face, this may seem like mere commercial work, given the focus in his writing on mask-wearing and performativity, one is inclined to believe that every endeavor Mishima embarked on in his life (including his dramatic suicide), was a part of his creative project. Thus, in this case, the desire I have to read through and consume everything he’s ever created is a foolish one, as, in order to do this successfully, I would have to spend my life studying his life. Instead of doing this, I’ve succumbed to a more banal, less compulsive, reading of his work. Every few years I read another one of his novels. Every few years I watch another one of his films. Sometimes I’ll do two in a row, but I’ve never gone on a longer Mishima binge.

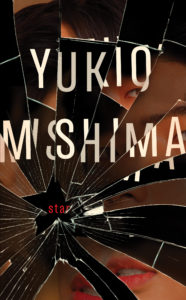

It is in this context that I was thrilled to learn of Star, a new addition to the English-Language Mishima cannon recently published by New Directions. Written in 1961 and newly translated by Sam Bett, Star is rendered in exacting contemporary prose. The sentences are generally short and declarative, and the word choice is refreshingly mundane. This linguistic spareness allows the heated subject matter of Star to emanate through the cracks of the sentences.

This spareness also creates a sense of emotional coldness on the part of Star’s narrator, Rikio, a young, Ryan Gosling-like movie star heartthrob who seems completely of our time. Surrounded by the strangeness of stardom (the endless fan mail, not being able to go out in public, young girls confessing via letter that they masturbate to his face, thousands of screaming fans waiting outside every venue he exits, the tabloids tracing his every movement), Rikio falls in love with his unattractive assistant, Kayo, who privately parodies the starlets that Rikio stars against, and makes fun of Rikio’s fans, and Rikio’s “little lily bud” to his face. Rikio’s descriptions of Kayo, and of why he loves her, focus almost entirely on her body and her performance of ugliness. Rikio claims, with admiration, that Kayo goes out of her way to make herself look even uglier than she is.

In this way, Star, like much of Mishima’s work, is about the relationship between the inner and outer self. Importantly, Rikio’s admiration for Kayo is not just the elaboration of a metaphor, a suggestion that all our interior selves are ugly, and therefore Kayo is more pure because her outer ugliness better matches her ugly interiors. Rather, his attraction to her expert performance of ugliness points to the way we, as humans, cannot avoid performance. From Rikio’s descriptions of her, I had to wonder if Kayo, not Rikio, was the better actor.

Rikio lovingly describes the specifics of Kayo’s performance of ugliness at length. At one point, while waiting for the next movie scene to begin shooting, he narrates:

Kayo knit the sweater sloppily on purpose. She made it fit wrong for her body, in a blousy shape long out of style. Knowing her, at some point later in the year, once everyone had forgotten all about her summer knitting project, she’d show up in the sweater and crouch down at the back of the studio, waiting to overhear their whispered laughter.

Because I knew what she was up to, that half-finished turquoise sweater seemed to me, from my vantage in the loft, like the very hue of her nefarious intentions.

This was apt knitting for summer. Her fingers maneuvered through the heart of it, as if secretly laboring to humiliate every worldly convention that the climate and the seasons had to offer.

But most of all this patch of turquoise yarn in the darkest corner of the set was a thing of beauty, like a virgin spring, a calm collection of her artifice.

Here Rikio makes clear that his admiration for Kayo’s performance of ugliness is twofold. He admires her for the skill, foresight and dedication with which she plays her part of the ugly woman. Importantly, he also admires that, unlike his chosen life role as a heartthrob, Kayo’s chosen role is one that goes against the grain of societal expectation. Society wants its citizens to lust after beauty and power. But here Rikio admires Kayo’s intention to “humiliate every worldly convention” with her steadfast intention to wear unfashionable clothing.

Despite Kayo’s large presence in the book, and long passages describing her and her performance of ugliness, we learn little about her background and personal desires. Rikio does question, at the end of the book, whether she is real. But this questioning comes at a time when he is questioning the realness of everything. Rikio has been on set for months, shooting scenes out of order under fluorescent lights for twenty hours. He describes being disoriented by the fact that time in the real world is linear, as opposed to cut up and shuffled into scenes that are filmed out of order.

At one of the darkest points in the book, feeling completely detached from reality and unable to process what is real and what is a movie, Rikio tells Kayo that he is contemplating suicide to which she replies, “You’re twenty four, at the top of your game. A heartthrob. A movie star, more famous by the day. No poor relatives to take care of, in perfect health. Everything is set for you to die. If you died today, maybe everybody would forget you. Not like you’re James Dean or anything, but maybe they’d love you even more, and pile so many flowers on your grave that there’d be no more room to leave them. But what difference does it make?” To which Rikio replies, “You’re right. It makes none.”

In this moment it appears that Kayo had poked through Rikio’s delusional, famed existence and made him see that, like any other human, his death, no matter if he commits suicide or dies of old age, will be a boring and deeply human event. Death as a universal democratizes Rikio with his fans. Rikio finds this democratization upsetting.

Shortly prior to this scene, Rikio attends a party without Kayo that is filled with the country’s richest people. No one in the room pays Rikio any head, and, when introduced to several women who don’t know who Rikio is, Rikio internally assumes that these women are only pretending not to know him. He assumes that the wealthy women’s refusal to recognize him and fawn over him and tell him about his recent performances is an act meant to manipulate him and seduce him. For Rikio, everyone is always acting.

This complex, psychological portrait of celebrity is a propulsive, enduring narrative that eerily predicts our contemporary digital tensions of the self. With smartphones’ advanced cameras hooked to all our palms, one’s own body, and how one chooses to portray it in photos and videos outwardly, is no longer a topic that solely encompasses celebrity. Movie stars and civilians alike now struggle with how to best present themselves visually to masses of people that they may never meet.

This bizarre, constantly required performance of a curated self causes all of the same discomfort and anxiety in its modern participants as it does in Rikio as an actor. The crumbling of Rikio’s lived reality and the delusions he builds for himself seem so familiar because they read like something anyone who has ever participated in social media has, at some point, encountered. In this way, though written nearly sixty years ago, far before the advent of social media celebrity culture, Star speaks to our modern contradictions of the inner and outer self masterfully. It also accomplishes a fascinating and singular interrogation of power, and how, whether by wealth or physical attractiveness or fame, people are able to build a delusional world for themselves in which they believe they share nothing, including death, with the rest of humanity.

Rita Bullwinkel is the author of the story collection Belly Up, which won the 2018 Believer Book Award. Translations of Belly Up were published this month in both Italian and Greek. Bullwinkel’s writing has been published in Tin House, Conjunctions, BOMB, Vice, NOON, and Guernica. She is a recipient of grants and fellowships from The MacDowell Colony, Brown University, Vanderbilt University, Hawthornden Castle, and The Helene Wurlitzer Foundation. Both her fiction and translation have been nominated for Pushcart Prizes. She lives in San Francisco.

This post may contain affiliate links.