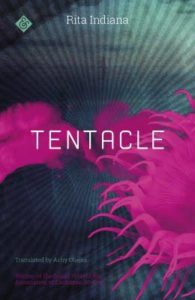

[And Other Stories; 2018]

[And Other Stories; 2018]

Tr. from the Spanish by Achy Obejas

In the aftermath of the 2024 tsunami that knocked out Venezuelan biological weapons stored off the coast of Hispañola and caused an ecological crisis, Dominican President Said Bona turns to his personal santera Esther Escudo for help. Surrounded by acid rain and epidemics, Esther, also known as Omicunlé, offers up her transgender assistant and former sex-worker Acilde as the country’s savior. With the help of a magical anemone and in exchange for the gender-reassignment drug Rainbow Bright, Acilde travels through time and embodies the avatars of a 17th-century pirate named Roque and an Italian philanthropist named Giorgio in the early 2000s, all to establish and fund a marine biology laboratory focused on the preservation of coral reefs and protecting the island from future tidal waves. By manipulating the Dominican art market and possibly forcing one artist into a mental breakdown, Acilde is able to avert the disaster and rethink what it means to control one’s body in a hypertechnological future.

This description only covers a fraction of what actually happens in Tentacle, Achy Obejas’s English translation of Rita Indiana Hernández’s La mucama de Omicunlé (2015). Within this time-traveling traveling narrative, Hernández’s novel offers a critique of anti-Haitian racism in the Dominican Republic, the consumption of Caribbean artists on the international fine art market, and the exploitation of queer people and bodies. Passing references to the Dominican Revolutionary Party, the Jewish resettlement in Sosúa after World War II, and the country’s tourism industry add to the complexities of both the novel’s plot and its historical context. Rapidly transporting between eras and protagonists, Tentacle offers dizzying timelines and stories that are not meant to be easily followed. The time-jumping and chaotic nature of the novel reflects Hernández’s reading of the Dominican Republic’s past and future, neither of which can be explained through simple cause-and-effect relationships.

Author, musician, and performance artist Rita Indiana Hernández has become one of the most influential creators and voices in the Caribbean. Born in Santo Domingo in 1977 and currently residing in San Juan, Hernández cemented her status in the literary scene with the “La trilogía de niñas locas” (The Trilogy of Crazy Girls), which includes the books La estrategía de Chochueca (2000), Papi (2005), and Nombres y animales (2013). While Papi references zombies and the literary collage Ciencia succión (2001) muses on contemporary obsessions with technology, La mucama de Omicunlé is Hernández’s first science fiction novel. Hernández’s experimentation with the genre shines a light on the growing science fiction and fantasy scene in the Dominican, which includes author Odilius Vlak, illustrator Eddison Montero and filmmakers Raúl Marchand Sánchez and Juan Basanta. La mucama de Omicunlé also received critical acclaim, as the first Spanish-language novel to earn the Grand Prize from the Association of Caribbean Writers and as a finalist for the Biennial Mario Vargas Llosa Prize for Novels.

Beyond the science fiction-inspired survey of the Dominican history, Tentacle speculates on what it might mean to adapt and survive in the future. Acilde, a trans man who risks everything for a reassignment procedure, rejects the normative understandings of the body and gender binaries that are still pervasive throughout this future society. This corporeal flexibility appears to be a key to survival, and is connected to the presumably government-assisted cyborg enhancements within her body. Acilde’s cyborg body, which does not appear out of the ordinary in this future world, is read as both an asset and liability to their continued survival. The operating system implanted inside them grants the ability to transfer files and play music videos on their eye-screens, forging community and offering much-needed distraction. At the same time, an internalized data plan facilitates police surveillance and an attacker is able to easily hack Acilde’s operating system with a quick punch to the sternum. That gender binaries are still maintained and emphasized in this hyper-technological and hyper-connected world speaks to the historical and present resilience of these violences; Hernández seems to be saying that it will take more than a few implanted microchips for society at large to honestly rethink the ways in which bodies are classified and treated.

Acilde’s plan to save the island from ecological collapse involves an innovative mix of Afro-Caribbean religious powers and internet connectivity. Their use of Roque and Giorgio as avatars echoes an earlier reference in the novel of young Dominicans using virtual reality video games to escape their financial and political precarity. In these games, users can either embody dancers in a 1970s disco or soldiers at war; either option offers the chance to reassert their physicality and escape a precarity built on government corruption and economic crisis. This escape via virtual reality highlights both the technological ingenuity of younger generations and their lack of hope that corporeal freedom could exist in physical world beset by exploitation, consumption, and discrimination. By redefining the limits and shapes of bodies through technological and spiritual means, the novel suggests models for what corporeality may look like in future dystopias.

The most striking difference between Hernández’s original and Obejas’s impressive translation is the dramatic change to the title. I had originally assumed that this was based on the difficulty surrounding the word “mucama,” which loosely translates to “maid,” since in the context of this novel that word could be seen as a reduction of the relationship between Acilde and Esther. (This reasoning was quickly squashed, as Acilde is referred to as Esther’s maid in the translation’s second sentence.) No matter the reason for the change, the new title caused me to read the translation with an altered focus. The original title frames the novel around Acilde, the individual tasked with saving the country. The translation’s title places the spotlight on the anemone, a magic-imbued aquatic creature that grants the protagonist access to spiritual realms and time-traveling powers, highlighting the importance of the sea within Afro-Caribbean religious traditions, along with the connection between ecology and the project to create a more sustainable Dominican future. The juxtaposition of the anemone and Acilde’s government-provided computer suggests that a combination of technological and spiritual literacy may be the key to navigating our imminent ecological crises. This also disrupts the hierarchy that values science while disregarding belief. Tentacle and other novels that speculate on the future of Afro-Caribbean religion, such as Erick Mota’s Habana Underguater (2010) and Nalo Hopkinson’s Brown Girl in the Ring (2001), challenge the assumed supremacy of hypertechnology and scientific knowledge over forms of power based on religion, belief and faith.

There are other ways in which the translation into English transforms the text, though not in a way that takes away from the novel’s meaning. The nature of the Spanish language makes it easier to omit pronouns, which Hernández often does when referring to Acilde. Obejas, on the other hand, is forced to choose feminine and masculine pronouns, respectively, before and after Acilde’s gender-reassignment. There are also moments in the original novel in which the sudden appearance of English within a sea of Spanish forces the reader to reconcile the meanings behind these inclusions. One example of this is the “Rainbow Bright” drug, a seemingly miraculous scientific advancement that is both prohibitively expensive and procured via black market channels. Another example is the augmented reality application “PriceSpy,” integrated into Acilde’s cyborg technologies, which automatically assigns prices to objects and people in view. This tool both facilitates and homogenizes capitalist consumption, as it does not recognize informal markets. Finally, the line of horrific, Chinese-built robots tasked with hunting and disposing of Haitian refugees bares the English-language motto “To clean up.” As a clear reference to the historical marginalization of Haitians in the Dominican Republic—including the 1937 “Parsley Massacre” under Rafael Trujillo and the more recent mass deportations of Dominicans of Haitian descent—the inclusion of an English tagline on a weapon that automates state violence forces the reader to recognize both US and international influence on and responsibility for past and future injustices on the island.

Among all the variegated characters in the novel, some written with dynamic histories and others intentionally left as caricatures, Argenis is one whose story remains unresolved. The misogynistic Dominican artist is unintentionally and unknowingly caught up in Acilde’s scheme after being stung by the same magical anemone in the early 2000s. Argenis is granted similar time-traveling powers, though without the ability to control them, and finds himself stuck between the 17th Century and his present life. More aware of what is going on than the other participants in his art collective, Argenis suffers a nervous breakdown when attempting to articulate Acilde/Roque/Giorgio’s plan. Though Argenis is escorted away as Giorgio and a younger President Bona celebrate the laboratory’s financial windfall, Hernández’s latest novel, Hecho en Saturno (2018) picks up the artist’s story as he puts his life back together, battles drug addiction, and attempts to reconnect with his father. That the continuation of Argenis’s story reverts back to Hernández’s brutal, realistic style highlights the importance of her use of sci-fi to tell Acilde’s story. In Tentacle, the manipulation of science fiction tropes is not a gimmick or trick, but a way to illustrate how impossibly intertwined the many forces are that have shaped the history of the Dominican Republic. By showing what disasters could happen in the not-so-distant future, Hernández also reminds us that we still have the ability to affect change, even if our time to do so is quickly running out.

Samuel Ginsburg is a Lecturer of Spanish at the University of Texas at Austin, where he earned a PhD in 2018. He studies representations of bodies and technology in Cuban, Dominican, and Puerto Rican science fiction.

This post may contain affiliate links.