In The Argonauts Maggie Nelson describes a conversation with her partner about an X-Men film:

That’s what we both hate about fiction, or at least crappy fiction — it purports to provide occasions for thinking through complex issues, but really it has predetermined the positions, stuffed a narrative full of false choices, and hooked you on them, rendering you less able to see out, to get out.

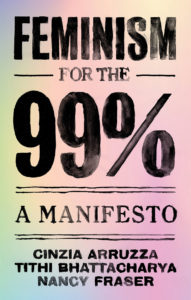

Neoliberalism is a crappy fiction. In eleven theses and fifty-seven pages Feminism for the 99%: A Manifesto by Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya, and Nancy Fraser demonstrates it as such, identifying the crisis of society as not only financial, but “simultaneously a crisis of economy, ecology, politics, and ‘care.’” These intertwined crises share as their root cause neoliberal capitalism. Inherent in the structure of neoliberalism is the dissociation of the economic from the political. In addition, there is the claim that social life should be allowed to freely interact with the ‘free market,’ as though this world and the people in it are not what allow this system to exist and proliferate in the first place. Inherent in the structure of neoliberalism is its presentation of itself as the only path forward.

Against this, Feminism for the 99%: A Manifesto “champions the needs and rights of the many — of poor and working-class women, of racialized and migrant women, of queer, trans, and disabled women, of women encouraged to see themselves as ‘middle class’ even as capital exploits them,” while aiming to become “a source of hope for the whole of humanity.”

Writing a feminist manifesto is a “daunting task” as Arruzza, Bhattacharya, and Fraser well know.

Nevertheless, they work towards presenting an alternative that turns away from divisive history, including that of feminism, without propagating false presumptions of homogeneity. Breaking with a historical feminisms entanglment with racism and imperialism, Arruzza, Bhattacharya, and Fraser also reject “abstract proclamations of global sisterhood” that do little to address the differing manifestations and interdependencies of oppression.

***

This is a text about solidarity.

Feminism for the 99% refuses to seek or provide for a middle ground that would merely feed into the systemic causes it wishes to free itself from. It avoids centrist compromises and rejects the notion that the two seemingly opposing viewpoints of conservativism and liberalism, which in actuality serve and seek to maintain the same status quo, are the only options. Instead it poses the questions we need to ask about the kind of world we want to build such as, “Where will we draw the line delimiting economy from society, society from nature, production from reproduction, and work from family? How will we use the social surplus we collectively produce? And who, exactly, will decide these matters?”

While right-wing movements seek to regain fabricated ‘traditionalist’ notions of femininity, sexuality, and nationalism, restricting the rights of those who do not conform, liberal left-wingers or ‘progressivists’ equally attempt to curtail the efforts of feminists, anti-racists, and environmentalists by employing legitimate rhetoric and grievances towards merely diversifying hierarchies rather than abolishing them. Feminism for the 99% rejects both of these paths because both are in service of the neoliberal capitalist system we have found ourselves in; it is this system itself that they “intend to identify, and confront head on, [as] the real source of crisis and misery.”

This manifesto describes the myriad of ways that neoliberal capitalism invades our everyday lives: through gender, sexuality, healthcare, and even the environment, to scratch the surface. At the same time, it highlights capitalism’s insistence on a regulatory divide for the sake of the ‘health’ of the economy, which is always prioritized over the health of the people who participate and generate that economy.

The division between these two forms of control is an illusion; there is no division at all, as both work fundamentally together. This becomes particularly clear when we look at what the manifesto calls “social reproduction,” where Arruzza, Bhattacharya, and Fraser point out that while capitalism did not come up with misogyny and sexism — tale as old as time, etc. — all on its own, it did create “new, distinctively ‘modern’ forms of sexism, underpinned by new institutional structures.” Key to these modern forms of oppression, the manifesto explains, is the separation of “the making of people from the making of profit.” The task of creating and sustaining the people who make up society is relegated to women and treated as an afterthought to the true goal of making profit, even though people-making sustains not only biological life but the act of production itself. While largely a feminist issue, the organization of social reproduction is a system enfolded with racism and classism that can only be resolved by discerning the interdependency of domination.

There’s no need to look far for proof of this. In the United States, the healthcare industry is detrimental for everyone and malicious towards women, even more so towards women of color, and especially towards pregnant women of color. Rates of maternal mortality in the United States, where more than two women die every day of childbirth, are particularly vicious for black women who are 3-4 times more likely to die from pregnancy or delivery complications. Even while alive black women’s legitimate concerns are taken as incompetence, which often causes life-threatening delays in health care. In addition to providing few social services to assist with the task of sustaining people, capitalism devalues the very literal act of making people to the point of jeopardizing the lives of women.

The kind of “viciously predatory form of capitalism we inhabit today,” the manifesto explains, will simply keep draining natural, mental, and physical resources without replenishment, masquerading as a free market that rewards individual responsibility as though individual responsibility arises in a vacuum. But people have to do the work of making other people into people: this obvious truism, in the hands of Feminism for the 99%, becomes a furious call to action for the rights of mothers.

But this is no surprise. Capitalism’s existence and propagation is due to its historical and continual subjection of others. There is no longer any point in asking whether capitalism can be tenable without the oppression of an other; capitalism has proven, time and time again, that it is not. Its dependency on imperialism keeps it from coexisting with other systems, which is why historically countries that try to move in directions that are outside the economic interests of US companies are threatened with economic sanctions, imposed with economic sanctions, and more often than not intervened with in a coup: think of Guatemala in 1954 or Chile in 1973 for starters. It’s never been a better time to reject the “global pyramid scheme.”

***

The feminism in Feminism for the 99% does not go unquestioned. The issue, the manifesto states, is that mainstream media “equates feminism, as such, with liberal feminism.” Far from being a movement of solidarity, liberal feminism has worked to disseminate the values of neoliberal capitalism: at the expense of women, especially women of color and migrant women, while posturing as a feminism that empowers women to ‘lean in.’

To survive and see any real change, feminism must reject not only the far-right neo-traditionalists, but also the ‘progressive’ neoliberals on the left. Along the way, feminists need to turn away from “‘carceral feminism’ [which] takes for granted precisely what needs to be called into question: the mistaken assumption that the laws, police, and courts maintain sufficient autonomy from the capitalist power structure to counter its deep-seated tendency to generate gender violence.”

Feminism needs to go further than the assumption that passing laws will genuinely give people the freedom of rights they deserve. “By itself,” the writers dryly point out, “legal abortion does little for poor and working-class women who have neither the means to pay for it nor access to clinics that provide it.” Similarly, by itself, changing legal definitions of gender does little to provide feasible options for those seeking surgeries. For example, laws against gender violence do little if there are no service programs to give people the ability to leave abusive relationships in the first place.

For Arruzza, Bhattacharya, and Fraser, as three of the organizers of the International Women’s Strike, the first step lies in recognizing the power of striking. Citing the October 2016 strikes in Poland and Argentina, the manifesto is clear that these are neither hopeless nor isolated attempts: for example, less than twenty years ago Leymah Gbowee and her nonviolent peace movement brought the Second Liberian Civil War to an end. By identifying solidarity as a key force and interrogating the many forms of paid and unpaid labor, women are demonstrating the many different ways to strike and show solidarity in order to achieve not just economic aspirations but social ones. Aspirations for a system that does not rely on the subjugation of others and a system that values people-making because people-making is what allows a system to exist.

And we have new ways to reach one another and create this solidarity, moving beyond traditional media sources. Presently, women in Sudan are at the forefront of anti-regime protests, using a Facebook group to highlight mistreatment by the police. Hashtags and other online movements have turned what may have felt like a localized experience into a global reckoning; think of #MeToo resonating around the world, leading to legislative changes in China’s the Civil Code for the inclusion of a definition of sexual harassment in the workplace. As with carceral feminism, it takes more than legislation and rhetoric to enforce and maintain effective mechanisms, but the significance of bringing such rhetoric to the forefront should not be easily dismissed.

Feminism for the 99% acknowledges feminism’s own unsavory history of racism and xenophobia, as well as liberal feminism’s attempts of imposing a universality of feminism that is white and middle-class, and breaks from it. Calls for solidarity should not be mistaken for universalism of lived experience and existence. The only universalism is agreeing that we can co-exist in a world while moving against systems of oppression instead of supposing them necessary by-products. This is why a truly feminist movement cannot separate itself from anti-racism, anti-imperialism, environmentalism, or anti-capitalism, whose systems of oppression are now inextricably tied with neoliberal capitalism.

***

The questions we ask ourselves can and should be continuously changing as we as people grow and change. Due to the pathway that neoliberal capitalism has taken us on, what used to be regarded as fundamental political questions such as whether or not one believes in private property now have little relevance. This is because they fail to regard the actualities of the world neoliberalism produces. Such questions assume a vacuum of meritocracy unaffected by the history of patriarchy and imperialism and returning to these old questions maintains a world based on an erasure of that history.

This manifesto is not about outlining detailed courses of action towards an idealized goal. This manifesto is about putting forth the questions and ideas necessary to try to work towards something different that can only be realized by trying. This manifesto should be read and talked about and reread and re-talked about because it is only the beginning. We can decide to change how we consider and participate in this world. We have the ability to look at this system, the damage it has caused, is causing, and will continue to cause, and decide to move in a new direction. It is only through participation in this struggle that we may hope to learn more about the possibilities of one another and ourselves. And as we set out, Feminism for the 99% is the map we need.

Marina Manoukian is a Masters student in English Philology at Freie Universität Berlin. She likes bees and loves honey. Find more of her words and images at marinamanoukian.com

This post may contain affiliate links.