Erin Adair

It’s been two years since nearly every major media outlet in the United States (with the notable if expected exception of one) declared that we had gone through the looking glass and entered a “post-Truth” world. It has also been two years since we lost the novelist and semiotician Umberto Eco. Just as well for him, because if Eco’s February passing hadn’t saved him from having to hear the American press knell truth’s final demise the day after the 2016 election, I think he would have died anyway—from laughter—soon after.

Having recently reread a number of Eco’s works for a separate project, I was struck with the salience of his novels for prefiguring an alarming and increasingly mainstream current of far-right conspiracy thinking that Eco could never have known would arise in the United States nearly a half-century after he started writing fiction. On the whole, reading Eco in today’s context helped me articulate both a popular, misguided assumption about the supposedly “postmodern” vicissitudes of the author’s work as well as a popular, misguided assumption about the supposedly “post-Truth” discourse undergirding today’s right-wing conspiracy culture. Specifically, Eco’s novels and the age of Trump both tend to exhibit such a supple and at times volatile interplay of reality and the (occasionally ridiculous) stories we tell about it that it is reductive to approach either by hunting for stable meanings and universal truths or by embracing unbounded semiotic play. Both Eco’s work and our current situation require careful attention to the materiality of discourse and the discursivity of material reality to articulate a praxis commensurate with the strange alchemy that unites them.

These thoughts were first prompted on May 29th, the day ABC kiboshed the barely revivified Roseanne after its namesake’s late-night Twitter meltdown, as well as the day I happened to finish rereading Foucault’s Pendulum. This chance convergence led me, out of boredom or fate, to sketch an admittedly silly T-chart comparison of the work of a renowned writer and that of a racist comedian. Predictably, I didn’t get much—bullet point one: Barr’s Trump-era-inflected Roseanne reboot as well as what I consider Eco’s most unjustly maligned novel both received lukewarm reviews among critics upon release, despite both achieving substantial popular success. Bullet point two: Barr’s now well-known Twitter tirade and Eco’s 1988 work both betray a morbid fascination on the part of their respective authors for deep-left-field conspiracy theories. But while Eco used these as fodder for Foucault’s Pendulum and his other fictions, Barr lives the fiction, believing in all good faith that the world she lives in is rotten with unseen puppet masters and shadowy plots to control and manipulate sheeple too blinded or comfortable to wake up to the truth.

The manifold uniting the various flavors of paranoia Roseanne Barr and a disturbingly large amount of her ideological cohort partake of is the QAnon conspiracy, a far-right grand narrative that started to take shape several months ago on 4chan’s unabashedly wingnut /pol/ board and which has figured heavily in Barr’s recent ravings. Since its inception QAnon has developed into an umbrella theory uniting nearly every conceivable intrigue and machination that populates the anxious underside of the conservative psyche, from the death of Seth Rich and the Benghazi debacle to the postulations that George Soros leads a worldwide shadow government and that your local Planned Parenthood peddles fetal tissue out of its back door. The overall QAnon plot, however, begins with the assertion that the Mueller investigation is not focused on the collusion between the Trump campaign and Russian operatives, but is actually working with the Trump administration to investigate the enemies of the right, principally those associated with the Clintons and the Obamas (Valerie Jarrett, the Obama aide Roseanne clumsily took aim at on May 29th, is a massive figure in the conspiracy). “Q,” the anonymous /pol/ poster behind this story who is so named because of his/her claim to high-level “Q-clearance” in the current administration, alleges that many have already been indicted and are currently under surveillance until the time is ripe for “The Storm” (AKA “The Great Awakening”) when all enemies of the people will be rounded up and Donald Trump will be able to usher in a new age of prosperity unhindered.

The primary crimes of which the bastions of the mainstream American left stand accused together constitute the strangely omnipresent boogey monster of today’s online far right: Satanism and child sex trafficking. If you’re getting a whiff of Pizzagate at this point, it’s because you’ve been paying attention—the focal, centrifugal power of the QAnon narrative is its ability to subsume and rework any element fed into it into a massive network of child sex traffickers operating under the aegis of a devil-worshiping Democratic party. The primary mechanism for the growth of this story is Q’s method of “dropping breadcrumbs,” whereby he/she deploys short bursts of fragmentary information, vague predictions, and rhetorical questions that his/her followers (who call themselves “bakers”) connect and arrange until a satisfactory addition to and legitimation of the overall plot has been fabricated. In April 2018 an application called “QDrops” appeared in the Apple App Store and Google Play store, allowing bakers to keyword search archived Q posts so as to better facilitate the ars combinatoria of their mythos—if there is any preliminary doubt as to the story’s popularity, it should be noted that QDrops nearly crashed both app purveyors, instantly becoming one of the most downloaded applications of 2018.

This brings us to the real issue. Namely, as ridiculous as the story surrounding the mysterious “Q” poster is—and with friends like Roseanne Barr, Alex Jones, former MLB pitcher Curt Schilling, attempted abortion clinic bomber Cheryl Sullenger, and D-list actor Isaac Kappy, who needs enemies—the story spun first from 4chan’s /pol/ board has actually made serious traction in the mainstream. Sean Hannity has referred to it approvingly, the official Twitter account for Florida’s Hillsborough County promoted the conspiracy, and WikiLeaks has engaged in some “baking” of its own. Offscreen, QAnon believers conducted a march on Washington to promote the conspiracy on April 7th, 2018, and as of August, QAnon truthers have begun seriously swelling the ranks of Trump-rally attendees, with many major media outlets beginning to cover the narrative while some GOP members judiciously attempt to distance themselves from the story. It is therefore little wonder that on June 28th Time Magazine named Q one of the most influential people on the internet in 2018.

This influence, as hinted above, lies in the incredibly powerful story-construction model Q has put in motion. Dropping only hints, Q encourages self-styled investigators to trawl every nook of major and minor news media, every politician’s slip of the tongue, every dubious paper trail, every stilted syllable out of the president’s mouth until there is no event or word, however negligible, that does not fit neatly into a cosmology over which a nearly omniscient, four-dimensional-chess-playing Donald Trump calmly resides, waiting for his opportunity to vanquish evil for good and all.

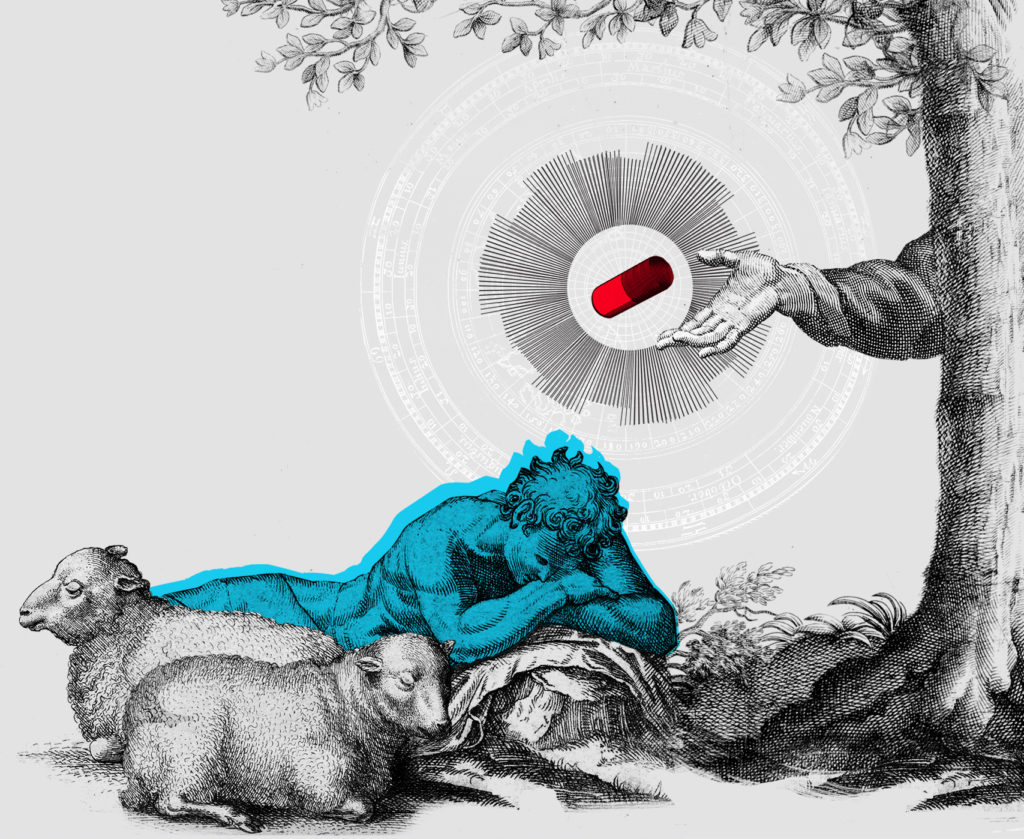

When you wade into the QAnon community, the reality-distortion field that appears to envelop believers upon buying in (an initiation they refer to as “taking the red pill,” borrowing the Matrix-derived language used by the equally deranged incel community) takes on an almost irresistible virulence. For example, in writing this article I began to wonder how it would be taken were it to somehow filter into the QAnon echo chamber—I imagine I would first be identified as a psyop propagandist for the deep state detracting from the true wickedness of our satanic, pedophilic overlords; soon after I might be vaunted as an undercover baker injecting yet more consciousness of Q’s revelations into the public under the cover of incredulity and (perhaps a bit too much) snark . . . Following the white rabbit (another of the QAnon community’s favored phrases), I even now can’t help but wonder whether all these meta-levels of self-analysis would, when followed through to the end, result in a sudden, excruciating revelation of myself as yet another drop betokening the coming Storm, another tentative cock-crow preceding the Great Awakening.

That, after all, is the power of conspiracy thinking—sooner or later, everyone is implicated and we all become characters in the plot. To return to Roseanne, what was most fascinating about her May 29th meltdown was that at the very same time she began to walk back her comments about Valerie Jarrett, she was furiously liking tweets about QAnon, specifically a few praising Roseanne herself for bringing more attention to the narrative. Thus Roseanne’s idiotic and racist attempt at a joke almost instantaneously transmogrified into a martyrdom for the QAnon cause; what looked like a seriously troubled and unfunny coot’s sleeping-pill induced bumbling becomes, in the bakers’ ovens, a shrewd agent provocateur’s offer of the red pill for an as-yet-slumbering American public.

Erin Adair

Precisely this kind of narrative/reality warp resulting from an all-encompassing conspiracy theory generated through the creative combination of otherwise free-floating fragments of dubious information constitutes the nucleus of Umberto Eco’s Il pendolo di Foucault. In the novel, published exactly thirty years ago, a group of vanity press editors starts a game of feeding bits of classic conspiracy theories—from Templar and Illuminati shadow governments to Nazi colonization of the hollow Earth—into a computer named Abulafia. Abulafia, like its medieval Kabbalist namesake, puts together in various increasingly baroque combinations the data it receives, generating a more and more convincing narrative that weaves together every major player in conspiracy history from Paracelsus and the Man in the Iron Mask to the Rothschilds and the CIA. The editors first use Abulafia’s inventions to help lure in true believers to their publishing house—dupes they refer to as “Diabolicals” who are willing to self-finance publications of their sundry ravings at whatever price—and begin to playfully compete with one another over who can articulate, in tandem with Abulafia’s machinations, the most broad-ranging and convincing narrative of human history, accounting for every shadowy global conspiracy imaginable—in the original Italian, il complotto dei complotti. Their game then takes on a capital G, progressively taking over their daily lives as the editors begin to seriously believe their own story, which increasingly seems to fill the lacunae left in traditional history and explain more in heaven and earth than had ever been dreamt of in their pre-Game philosophies.

The narrative volta of nearly all Eco’s novels tends to occur at this point—when the main character’s forgery or fabulation blurs into reality and he himself cannot help but start to believe his own story. For the main characters of Foucault’s Pendulum, the point at which fiction starts seeming “real” is when their recovery of a bona fide medieval document appears to verify the plot of the Game as they and Abulafia had hitherto elaborated it, seemingly providing incontrovertible evidence that the editors had actually happened across a real millennia-long Knights Templar plot for world domination. The climax of this supposed plot occurs upon the latter-day Templars’ repossession of the Holy Grail, which would allow them to control the telluric forces of the earth and thus wield inestimable control over every mortal power. Eco employs the potent titular image of Foucault’s pendulum hanging from the nave of the Paris Conservatoire as the narrative figuration of this all-encompassing, all-explaining zero-point that would confer on its possessor complete omnipotence and omniscience. Opening with a soliloquy on this “mystery of absolute immobility,” the main character intones:

The Pendulum told me that, as everything moved—earth, solar system, nebulae, and black holes, all the children of the great cosmic expansion—one single point stood still: a pivot, bolt, or hook around which the universe could move. And I was now taking part in that supreme experience. I too moved with the all, but I could see the One, the Rock, the Guarantee.

It is in meditating on this image in relation to their supposed Templar document that the editors “discover” that the unifying point of all global conspiracies imaginable leads toward the “Omphalos, the Umbilicus Telluris, the Navel of the World, the Source of Command.” And it is under the pendulum that the novel reaches its climax, when the editorial group’s de facto leader, Jacopo Belbo, in the hands of a group of Diabolicals who go by the name of the TRES (a secret society the editors and Abulafia made up), is murdered for not giving up the location of the map to the Umbilicus Telluris (the existence of which Belbo and his compatriots realize only too late that they themselves had concocted). At the zenith of the novel’s action, the point where all points converge, the critical, pendular position of “suspense” in more sense than one, it is revealed that Belbo’s demise is his own doing, having released the Game on a world prepared to take its combinatory fabrications seriously.

It’s just before Belbo dies that the main character, aptly named Casaubon, surrenders to his girlfriend Lia the supposed Templar document that had initiated the editors’ first belief in the true magnitude of their Game. After just a weekend of research, Lia conclusively determines that the document does not indicate a thousand-year-long plot to take over the world by progressively gaining control over various telluric nodes on the Earth’s surface—it is, in fact, a shopping list.

This is the classic Eco denouement. After five hundred pages of interminable weaving through meticulously researched history and elaborately concocted legend, and after seeing most of the main characters die, the reader is confronted with the fact that the gravitational center around which the entirety of the novel revolves is completely void. The whole drama, given one very slight shift in degree, might not and probably should not have happened. This is the ultimate truth of the point by which the proverbial pendulum is suspended: It is not the Ein Sof, the alpha and omega, the ultimate unmoving mover that precedes, traverses, and exceeds us sublunar pawns in the great Game—it is, philosophically and geometrically speaking, of no substance whatsoever.

The revelation that there is no ultimate, central, and all-explaining truth to which we can finally anchor ourselves in Foucault’s Pendulum or, in fact, in any of Eco’s novels—that one’s Holy Text might be a semi-literate peddler’s shopping list or, as another more bluntly put it, that God is dead—is often the source of readers’ frustrations with the author’s worlds. Richard Eder of the Los Angeles Times had this to say upon the English-language publication of Foucault’s Pendulum in 1989:

Umberto Eco’s new novel is an artichoke with 641 leaves and not much heart. There is some real pleasure in artichoke leaves, but what with the work and the scratchiness you probably wouldn’t undertake one unless you thought there would be a heart in it.

Similarly Anthony Burgess begins his New York Times review by congratulating those “who actually manage to read it. For while it is not a novel in the strict sense of the word,” he writes, “it is a truly formidable gathering of information delivered playfully by a master manipulating his own invention—in effect, a long, erudite joke.”

Crucially Burgess, at least, gets the joke: “The [G]ame is not,” he writes, “a closed system. It puts out feelers to the real world.” Though the main characters are intimately aware of the Game as their own invention—their own text—their semiological chickens keep coming home to roost nonetheless, and the story they once invented as a diversion and scam begins to slowly consume, then take, their lives. If the pendulum is the ultimate joke, then the punchline is that when it starts swinging it ceases to be a joke at all. Thus the power of Belbo’s final appearance in the novel, hanging by his neck halfway down the swinging pendulum.

Eco, in the final analysis, resists those who insist that his fictions are mere postmodernist bacchanalia of signifiers with no referents—in news-speak, that they are “post-Truth.” Reality and fabrication, history and narrative, profoundly and reciprocally influence one another, and playing games (or Games) with one or the other can have lasting, destructive effects. Narratives of global conspiracy, after all, have historically been cobbled together to justify the oppression of already marginalized groups and solidify the supremacy of others. The Third Reich actively used conspiracy myths promulgated in such fabricated documents as the Protocols of the Elders of Zion to substantiate the genocide of the Jewish people, whom it alleged were members of a near-omnipotent, international cabal, a myth whose effects can be followed all the way to Trump and co’s recent taste for the anti-Semitic dog-whistle term “globalist.” Obsessions with global conspiracies indeed seem to be rife among those already in positions of privilege and power—for the US right of today, leftists somehow managing to keep a stranglehold on international affairs (and via a global, satanic, child-sex cult at that) despite conservatives’ clear control over all branches of the US government allows the right to maintain its self-styled image: downtrodden David valiantly battling liberal-mainstream, politically-correct, cultural-Marxist Goliath.

This same kind of thinking gave a swindler and reality television star the impetus to conduct an identitarian crusade demanding proof that the 44th US president was, in fact, American. And this same kind of thinking in part led that swindler and reality television star to the White House himself. “Conspi-racism” can be considered the portmanteau designating the form of thinking that leads white Americans to believe that getting rid of people who don’t look like them will solve their socioeconomic problems. Under the aegis of conspi-racism, it’s not the steady erosion of workers’ rights and protections since the eighties, decades-long wage stagnation coupled with out-of-pace inflation, deeply commodified health and prison industries seeking to maximize profit at the expense of actual life, the natural tendency of capitalism to drive down the cost of production no matter what . . . It’s black and brown people. Behold the Ein Sof, the Umbilicus Telluris, the Navel of the World, the all, the One, the Rock, the Guarantee, the point that Foucault’s Pendulum describes as

the luminous mist that is not body, that has no shape, weight, quantity or quality, that does not see or hear, that cannot be sensed, that is in no place, in no time, is not soul, intelligence, imagination, opinion, number, order, or measure. Neither darkness nor light, neither error nor truth.

Eco—whose boyhood trumpet performance at the funeral of a communist partisan killed by Mussolini’s forces inspired Foucault’s Pendulum itself—knows precisely how easily identity is marshaled as the “fixed point” around which the universe can be made to turn. The world of the persecuted white man and pernicious Brown or Black Other that needs to be expelled, subjugated, or destroyed at any cost is an absurd fiction, but it is a fiction that is structuring the lived reality of being in the US in 2018 (as well as one that, in one form or another, has largely structured the course of Western history itself). It is a fiction that today supports the increase in racially-motivated crime and encourages crypto-fascists to come out of the deep woodwork of obscure internet forums and speak on college campuses or serve as talking heads in the mainstream media. It encourages people to kill, or try to. For while we may laugh at the idea that the Clinton family operates a Satanic child-sex cult out of the basement of a pizza parlor, the reality is that a person took an assault rifle into that pizza parlor to—in his own words—“save the kids.” In October 2017, far-right conspiracist, habitual /pol/ lurker, and former Milo Yiannopoulos staffer Lane Davis stabbed his own father to death after claiming the latter was a “leftist pedophile,” echoing the central charge of the QAnon narrative. This June, Matthew P. Henderson stopped an armored vehicle on the Hoover Dam, leading to a ninety-minute standoff with police, for the purpose of demanding the release of an obscure Justice Department report that the QAnon conspiracy claims details the extent of child sex trafficking among government officials. Henderson spent his time in jail writing letters to President Trump with the sign off, “Where we go one, we go all,” Q’s own patented motto.

Both Eco’s and Q’s stories are those of people desperate for meaning, and of people willing to give them some semblance of it for profit, for power, or even for laughs. Our willingness to submit to a story that makes it all make sense—the complotto dei complotti—is as deep-seated and seemingly indelible in our psyche as the shadow of the dead God that Nietzsche describes in The Gay Science, as difficult to resist as the momentum propelling the pendulum that swings from the nave of the Paris Observatoire. The point to which the pendulum is tied is void, but a void can fit a lot—even everything—given the right perspective or the right storyteller. “If you alter the Book, you alter the world; if you alter the world, you alter the body. This is what we didn’t understand,” says one of the editors shortly before the Game, in its way, kills him. The final, inevitable choice Eco leaves us with may be to either seize the momentum of Foucault’s pendulum or hang from it.

Cory Austin Knudson is a graduate student in Comparative Literature and Literary Theory at the University of Pennsylvania. For him this mostly means writing about porn, Nietzsche, and climate change, and trying to prove how intimately related those three really are.

This post may contain affiliate links.