Like so many people, I am mourning the passing of Ursula K. Le Guin. I’ve been reading her words for thirty years. They’ve embedded themselves so deeply into my consciousness that I can’t always separate her thoughts from mine. As I wade deeper into my 40s, I keep thinking of one story in particular. I read it as a teenager, and for the longest time could remember only a vague outline. A team of anthropologists exploring a distant planet full of sexy young women and hunky young men. An observation that the women don’t seem to have their own thoughts until they age out of attractiveness and the young people in charge stop paying attention to them. A discovery that that’s how the real culture of the planet was being created: by socially invisible middle-aged women. A “twist” ending. That’s all.

Like so many people, I am mourning the passing of Ursula K. Le Guin. I’ve been reading her words for thirty years. They’ve embedded themselves so deeply into my consciousness that I can’t always separate her thoughts from mine. As I wade deeper into my 40s, I keep thinking of one story in particular. I read it as a teenager, and for the longest time could remember only a vague outline. A team of anthropologists exploring a distant planet full of sexy young women and hunky young men. An observation that the women don’t seem to have their own thoughts until they age out of attractiveness and the young people in charge stop paying attention to them. A discovery that that’s how the real culture of the planet was being created: by socially invisible middle-aged women. A “twist” ending. That’s all.

But it kept popping into my head. I thought of it when a friend and I went out for 40-something birthday drinks and were treated like benign ghosts at the bar—and it was great. I thought of it every time I was passed over for a job I would have easily gotten when I was 28. Less great.

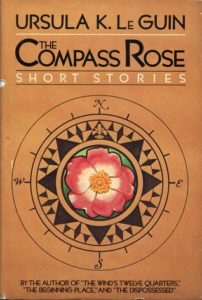

Midway through my 43rd year, I was thinking of the story almost every day. As much as I’d gained from think pieces and comedy sketches on the subject of becoming invisible, I realized that what I needed was a coming-of-middle-age story that resonated the way traditional coming-of-age stories had in my teen years. So I spent a day trying every combination of search terms I could think of to track down this tale. I finally found it tucked in the middle of Le Guin’s 1982 collection The Compass Rose. I kept missing what was right under my nose because the title, “Pathways of Desire,” didn’t ignite a single spark of recognition. But when I read the first paragraph, I was certain. This was The Story.

I settled in and re-read it for the first time in 27 years. As missing pieces of plot pooled into the hazy spots, they mingled with my own memories. I recalled how I found it the first time. I was 16 and experiencing an almost physical pain at having finished all of Le Guin’s Earthsea books (The Tombs of Atuan, told from the point of view of a relatably self-serious teenage girl, had become my new Favorite Book Ever). To fill the void, I’d worked my way through the rest of Le Guin’s output, including The Compass Rose.

At 43, I thought how funny it was that a story I hardly remembered could imprint itself on me so deeply. Right, of course, it’s the story of three researchers on a beautiful but boring planet. The inhabitants (the Ndif) don’t seem to have any rituals or kinship systems, or even much personality. The only social structure is based on age. The Young Women are all conventionally attractive and like to dance naked and have sex. The Young Men like to hunt, copulate, and watch the naked ladies dance.

Gradually, the researchers realize that the society’s rudimentary language is based on English, even though nobody from Earth has ever been there. Even stranger, the Middle-Aged Women and Old Men (there are no Middle-Aged Men), having been dismissed from what little culture existed, are inventing new words and ideas and rituals; they are expanding the boundaries of their world. In the end, the researchers piece together that the planet was created in the imagination of a fifteen-year-old American boy named Bill.

The first time I read it, I think I was enchanted by the idea that the worlds we invent in our heads are real somewhere. I’m still enchanted by that idea, but perhaps for different reasons. If our words take on material form (and I’m certain they do), that’s a big responsibility. We should do our best to make them interesting. Bill got a whole planet, and the best he could come up with were boobs and sports (I leave it you to make the connection to the folks in charge of our own planet).

But that’s not what made me jump up and shout, “This! Yes! This is the part!” when I re-read it. That reaction was inspired by this: “The Young Women giggled; The Middle-Aged Women laughed. They laughed…as if they had been set free.” When they first age out of Ndif society, the Middle-Aged Women are bored and depressed. But after a while, they’re able to create more authentic lives because they’re not part of Bill’s fantasy anymore. As a teen, this story planted in my mind a new idea—that there could be a kind of freedom in growing old. This is not a notion that women—especially young women—are told very often. We spend most of our lives bombarded by the opposite message: women’s bodies, their legibility within the narrow confines of the male gaze, are the basis of their worth.

A few days ago, I thought of this story—the whole story now—again. I was out to eat with my partner, and a trio of young women walked by. I admit I commented on them first. Not assessing. It was just that they were dressed in what can best be described as My So-Called Life cosplay—flowery babydoll dresses, flannel shirts, Doc Martens, chokers, brown lipstick, the whole she-bang. As a Gen-Xer, this made me smile.

“They look uncomfortable,” my partner commented.

I hadn’t noticed at first, but he was right. I sighed. “It’s hard to be a girl.”

I felt their discomfort more keenly because at that age I sometimes dressed in almost the same costume. I remembered the giddy pleasure of dressing up with your girlfriends. Of pouring through Sassy magazine looking for styles you could replicate without access to money or cool stores. Of succeeding. Of leaving the house like three shooting stars and then shrinking, tugging at the hem of the dress, hitching up the thigh-high stockings that you coveted and saved up for and would never wear again. Huddling closer to your best friend. Because everyone was looking. And you weren’t yet sure if you were the kind of girl who wore babydoll dresses and thigh-high stockings, and you were only supposed to be that kind of girl if you liked being looked at. And all girls were supposed to like being looked at. But you didn’t get to choose who looked or when or in what way.

I remembered experimenting with different strategies for controlling who looked at me and how they reacted. Once, at my retail job, a drunk man wouldn’t stop hitting on me, and I thought I’d try telling him I was gay. When my Middle-Aged Woman co-worker saw him harassing me, she kicked him out of the store, but not before he yelled across the room, “Have you ever been fucked by a real man?” Lesson learned: lesbians do not escape the acquisitive male gaze (I was 19—cut me some slack).

I remembered being in my late 20s and finally mostly mastering both my style and my interaction with that constant, assessing gaze. Look pleasant but not too pleasant. Base-level friendliness can be perceived as an invitation, coldness as being a stuck-up bitch. Focus in the middle distance to avoid eye contact, but without looking like you were purposely avoiding eye contact. It all required an exhausting level of vigilance. Which is not to say that visibility was never fun. It must have been. Because I found myself missing it a little as I crossed the Forty Bridge and was handed my ladies’ size XL invisibility cape.

At one point in Le Guin’s story, the main character observes that some of the Middle-Aged Women were “more beautiful than the Young Women, a beauty which included missing teeth, sagging breasts, and stretchy bellies.” At 43 I understand this. People often say I don’t look my age. Maybe they have to say that. Or maybe the fact that I still don’t have a steady job or know what I want to be when I grow up has given me an adolescent glow. I’m pretty sure I look exactly 43. After thirty years of doing battle with my body over what shape it should be, punctuated by bouts of depression and anxiety when all my energy was used up just managing the daily necessities of life, I’m not one of those taut, Barre3 and Crossfit 40-somethings. I’m chubby. My temples are grey. My cheeks are ruddy with broken capillaries brought on by years of treating eczema with cortisone creams, and also just living on Earth and having a complexion that permitted a laissez-faire attitude toward sunscreen. I’m pretty sure I see reading glasses in my very near future.

I guess I’m Middle-Aged.

And I’m ready. Le Guin’s vision of coming-of-middle-age works for me, I think because being a chubby 40-something often feels like speculative fiction. It’s like I have a magic power. I get away things because people aren’t paying attention.On a bus recently, I saw a man pestering a much younger woman. She was trying to read a book, and he kept saying things like, “Is that a good book? You’re pretty into it. It must be good. What’s it about?” She had perfected the pleasant not bitchy not inviting tone and said she’d just like to read her book and not talk. It was veering into “You think you’re too good for me?” territory when I activated my superpower. I quietly took one step to the left and stood between them. Not engaging or making a scene. Just shifting. The man got bored and turned his attention to his phone. It was probably a coincidence, but I imagined him being confused, like, “Wait? Where did the sexy lady go? She was sitting right there, and now I can’t see her!”—totally unaware that a human woman was blocking his view.

I won’t lie: sometimes the invisibility cloak is a pain in the ass. Especially when it isn’t paired with a Middle-Class Stability Shield. Take those job interviews I mentioned earlier. Imagine the 30-year-olds who’ve maybe made better life choices than you being like, “Too bad she didn’t show up, her résumé looks great.” And you’re shouting at them, “Dylan! Kaitlin! I’m sitting right across from you!”

But mostly it’s OK. Because I was prepared for it to be OK. Le Guin gave me a gift 27 years ago, and I’m only now understanding how precious it is. The patriarchal gaze that seems so all-encompassing and powerful, that surveils and objectifies and sexualizes women, has a very small imagination and an even smaller attention span. It’s going to stop seeing us when we stop being part of its fantasy (and many will never be seen at all), and there are things about that that will suck. But we can follow the lead of the Middle-Aged Women of Ndif. We don’t have to accept the world—the story—that we were born into as it is. Instead of mourning our youth, we can work on shaping “Bill’s” idealized world into a real place worth living in. A place that recognizes the ugly bits (the story begins with a case of diarrhea) and looks for solutions to them.

“Pathways of Desire” isn’t among Le Guin’s most famous stories. Possibly it’s not among her best. But it captures this weird transition better than anything I’ve come across. Le Guin’s work reveals that we don’t come of age only once, as adolescents. It’s an ongoing process. There’s a kind of poetry to the idea that the same author who helped me become a Young Woman is helping me come-of-a-different-age. I’ll probably master Middle Age right about the time I realize I’m Old, but I think that’ll be OK, too. There’s probably an Ursula K. Le Guin story that covers it. In the meantime, I’m laughing as if I’ve been set free.

Sara Tatyana Bernstein, PhD writes about and teaches media, fashion, and cultural studies. She is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Liberal Arts at Pacific Northwest College of Art, and co-founder of Dismantle Magazine: Fashion, Popular Culture, Social Change. Her work has appeared on Racked.com and Inside Higher Ed, in Fashion, Style and Popular Culture Journal, Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty, and in several edited collections of scholarly essays.

This post may contain affiliate links.