Tr. by Tess Lewis

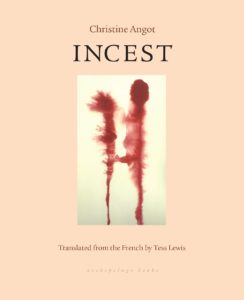

Incest, Christine Angot’s incendiary 1999 performative autofiction now translated into English for the first time, documents the mental breakdown of a Frenchwoman, also named Christine Angot. The inciting event of her madness appears at the start to be an obsessive three-month relationship with another woman, though the novel ultimately stakes the breakdown on a formative incestuous relationship she had with her biological father, whom she did not meet until she was a teenager. Angot relates the way her father shifts wildly and unpredictably from protector, to abuser, to victim helpless against his own desire. The desire drives him mad with guilt, which he pins on his daughter, for which he punishes her gravely, near fatally, even as she clings to him.

Incest is Angot’s way out of her guilt, a way to escape the voice in her head by banishing it to paper. The first half of the novel races in an unbroken chunk of text nearly 100 pages long, sentences unraveling, repeating, curling in on themselves and sprouting tendrils there onward, of self-hatred and acute self-awareness: “For three months, I thought I was condemned to be insane. I don’t know what I’m supposed to do anymore, I don’t know what I’m supposed to say. I’ll just tell this anecdote, I’m not Nietzsche, I’m not Nijinsky, I’m not Artaud, I’m not Genet, I’m Christine Angot, I have the means that I have and I make do with them. There will be an anecdote, too bad, an account of a trigger, it will be Christmas time, it will be descriptive. I’ll describe my insanity through a sudden insight. I was barely conscious of it until the previous page.”

In this story of incest, the Daughter lives in two worlds. In one, the good world, the abuse is a figment. It never happens, even as the bruises remain. In the other, the bad, He is all, the abuse is all. It is the daughter’s alpha and omega. Stockholm syndrome, the only way to cope.

In the good world, there are those who who peer into the insular world of incest, who know, who see the abuse, but for whatever reason cannot or will not act. If the daughter does reach out, she is not believed. Angot writes, after she finally confides in her half-brother about their father’s abuse: “His tone was impassive, he didn’t know whom to believe, his father had spoken to him about it, he had said I was making things up.” The incest world has its own parameters. Adheres to its own logic. In this world, the Daughter is nothing. She is only her father. So in the real world, the good one, she must write herself down. To see, objectively, the pain, the horror. The book is the only path from the bad world to the good. The only way to be believed. Angot continues after her half-brother’s apathy: “OK, fine, doesn’t matter. I’m fed up with talking about it. I’m happy the book is finished, happy.”

The first language the Daughter learns in the bad world, the language of self-hatred. The father injects her with this language, and hatred of womankind. This makes everyone in the bad world feel better. Then, the verbal abuse that objectifies the Daughter — bitches, slits, dogs — also functions as protection. She comes to see herself as an object. As a beast. Succubi, scum, single-celled organism who cannot help herself, and who cannot be helped. Angot turns to the language of self-hatred and women-hatred:

- ‘“I love women,’ how many times did we hear that? Saying “I love women” when you’re a man is easy. ‘I love animals’ is easy for a human.”

- “When I was little, I would wrap my arms around my mother’s neck and she would say, ‘my most beautiful necklace.’ Yeah, sure, a necklace of garbage. Which goes to show you what my father made of me and my mother, of our relationship, which was beautiful before we knew each other. When Leonore was born, I had a premonition of all this. That two women were garbage showing itself.”

- “I’m a dog looking for a master, no one wants to be my master anymore. And he, would he be willing to be my master again? Would I still know how to obey him? Would I know how to suck his old cock again right now, maybe his memory would come back?”

The 1999 recounting of Angot’s incestuous relationship shrouded the novel and the author in controversy, so much so that Angot was prompted to write a hasty follow-up in 2000, called Quitter la ville (Leaving the City). Here she insists that the statements of the work of autofiction are more performance than reality, autofiction instead of fact. A metafiction on society’s fundamental prohibition of incest. In fact, Angot describes her entire oeuvre as performative utterance. (For instance: throughout the novel, she equates her three-month lesbian affair with infections, sin, specifically, AIDS. But crying AIDS is her performative utterance. What she means is AIDS as in, a three-month stint of AIDS. That is, “for three months I believed I was condemned to die of that mortal illness called AIDS.” She performs AIDS. Her AIDS in turn performs queerness, her errant sexuality, and her hatred of it and her hatred of her queerness. She wishes to shake it like a cold.)

The male intellectuals who developed the theory of performative utterance in the philosophy of language and speech acts define them as sentences describing a subjective reality. Examples include: “I now pronounce you man and wife;” “I accept your apology;” “I do;” “I promise;” “I swear;” “I apologize;” “You’re fired.” Performative writing like Angot’s is derived from performative utterance. Performative writers attempt in their work to reflect the fleeting and ephemeral nature of a performance, the inherently flawed mechanisms of memory and referentiality of performance, before, during, and after. The performer is a new person in each stage. Worlds are divided, unrelated. The world at the beginning is not that of the end. Performance art theorist Peggy Phelan explains the appeal of a performative style as: “a statement of allegiance to the radicality of unknowing who we are becoming.” Performative writing promises no buttoned-up endings, no achievement of perfection. It refutes the notion of a progression, of a moving forward, the reaching of a completed end-point. It instead “enacts the death of the ‘we’ that we think we are before we begin to write.”

Because so little of her work is available in English, I must turn now to a surely-botched Google translation of Angot’s defense of her work and the duality of truth/lie within it. In Quitter la ville she says (I think): “I never want to hear again that the lives of writers are unimportant. They are more important in any case than books. It is the life of writers that counts. Know what it is. We hear the lie and we hear the truth, we hear the outside and we hear the inside . . . It is an act when one speaks. It is an act, it is not a game . . . It is not a testimony of shit as they say.”

But some contest (those male philosophers, again) that performatives are successful only if the recipients infer the intention behind the literal meaning. Therefore, the success of the performative act is determined by the receiving side.

And Angot’s work has rarely been received the way she says she intends it. In 2013, a woman sued her for €200,000 for invasion of her personal life for Angot’s novel Les Petits (The Little Ones). The tawdry details were culled directly from her life and “twisted,” almost causing the subject to commit suicide. Though Angot cried performativity, the subject insisted: “Everything is true in that book. It’s my life. She wishes me dead; she wants to destroy my children.” In the trial, Angot’s lawyer explained to the court that “auto-fiction” is a long-held tradition in France from Stendhal to Flaubert. “Christine Angot,” he claimed, “like Zola, describes reality.”

Her reality. Or the reality she wishes was actuality. In Incest, Angot writes an alternate ending for herself:

Control of this story and now I have it (let’s say). He’s lost his mind, Alzheimer’s. Me, I’ve got an edge over the incest. The power, the sadistic penis, that’s it, thanks to the pen in my hand, confidently, fundamentally. If I say “the hell with those who’ll read it” it’s because I’d rather have had something else to write about. That’s all. Writing is not choosing your narrative. But taking it, into your arms, and putting it calmly down on the page, as calmly as possible, as accurately as possible. So that he will turn over in his grave yet again, if my body is his grave. If he turns over again, it’s because I’m not dead. I’m insane, but not dead. I’m not completely insane either.

Angot is desperate for definitions, but the definitions are fickle and ever-changing. She returns to tentpoles of her stories like talismans, “licking,” the affair, her child, “Leonore, l’or,” “dog,” the clementine she ate from her father’s penis on a road trip. She searches for the reality in them, so that by returning to them, she will change with them, they will have changed within her. Even as she tells herself she will break free from these language anchors, (“I won’t write anymore, for example, ‘I licked her, this woman, whose child is a dog,’ I won’t write that anymore, what’s the point?”) she cannot help herself.

Perhaps the second language the Daughter learns then, after the language of hate from the bad world, the good language that she must learn in order to live, is the language of performativity. Of the subjectiveness of objectivity, and how living in the mind is and is not the external world. I cannot be that which I can observe, the Daughter tells herself. I am not this abuse. I am not him. I am many. This too shall pass.

Performative writing is an innately female act, because it has to do with being believed. Or disbelieved. And the ramifications of that truth. The gaze is too much for daughters. They cannot trust themselves before it. They must write themselves down, commit themselves to an object, and burn it.

“Incest is the book in which I present myself as a real shit,” Angot writes, “all writers should do it at least once.”

The objectivity of proclamation. Searing truth.

“Writing may only be doing that, showing one’s inner shit.”

But then, the Daughter questions. How can she be right, when she has been told for so long that she is not?

“Of course it isn’t. You’re ready to believe anything. Writing is not just one thing. Writing is everything. Within limits. Always. Of life, of one’s self, of the pen, of height and of weight.”

She changes with the pen. She is never all one. The word is talisman. But words, too, shall pass.

This post may contain affiliate links.