I hate the word “underrated.” I hate even more how often I feel compelled to use it. First there’s the self-fulfilling element—that deeming anything “underrated” can perpetuate the classification even further; one’s claim registered as corrective rather than insight. There’s also the problem of “underrated” having gone through what I call the adjective abattoir: the ubiquity of its usage has exhausted it of any live, substantive meaning. More importantly, though, I wonder if “underrated” is even the right word to bear the weight of that which we mean it to express. The word itself seems to refer to some sort of rubric, collectively agreed upon, by which the merits of someone or something are measured.

But this isn’t what we have in mind when we designate someone—say, a musician—as “underrated.” What we mean to do is to state an observed dissonance between that musician’s importance to us—our unerring belief in their brilliance—and the recognition (or lack thereof, as the case may be) they’ve been met with at large. Somehow, “underrated” has become the word we choose to contain and convey that felt disconnect. But the conviction of our sense of proportionality is predicated on two untenable pillars: that we have a nuanced understanding of what and how the public rates and values, and that we know what a proper estimation and appreciation would look like and how it would manifest for the artist in question; the artist, who—one would like to add—might hear more in “underrated” than the compliment intended.

Having thought this through many times and believing it to be true—I have, I do—I am left wondering why it is that I began the first draft of this essay with the one-sentence declaration, “Juliana Hatfield is the most criminally underrated musician of her generation.”

The second sentence would not come; I’d trapped myself by writing the first. I’d wanted to write an essay in which I could articulate, with reverence, the inestimable importance of Juliana Hatfield’s music in my life. I’d wanted to write an essay that bore keen and studied witness to her as an almost sadistically brilliant writer and performer, as vital now with her fourteenth record, Pussycat—an unrestrained tour de force on and of rage, the first masterpiece of Trump-era protest music—as she was in 1991 with her first solo record, Hey Babe. More than anything, though, I’d wanted to write an essay that expressed my secular prayer that the music Juliana Hatfield has released into the world in the more than 30 years she’s been a performer will stand the test not of time, but of the time-honored, unjust, and incontrovertible constancy of the erasure of women with something to say.

The second sentence would not come; I’d trapped myself by writing the first. I’d wanted to write an essay in which I could articulate, with reverence, the inestimable importance of Juliana Hatfield’s music in my life. I’d wanted to write an essay that bore keen and studied witness to her as an almost sadistically brilliant writer and performer, as vital now with her fourteenth record, Pussycat—an unrestrained tour de force on and of rage, the first masterpiece of Trump-era protest music—as she was in 1991 with her first solo record, Hey Babe. More than anything, though, I’d wanted to write an essay that expressed my secular prayer that the music Juliana Hatfield has released into the world in the more than 30 years she’s been a performer will stand the test not of time, but of the time-honored, unjust, and incontrovertible constancy of the erasure of women with something to say.

Yet, for several days, all I had written was, “Juliana Hatfield is the most criminally underrated musician of her generation.” Lazy and easy and empty.

That this essay is published, that you are reading it, does not suggest that I have arrived at the right way to talk about Juliana Hatfield’s music, why it matters to me, and why that mattering might matter to you. I’m not sure I have. If I communicate here even a fraction of what I’d hoped to, it has everything to do with the difficulties of communication that my attempt to do so presented. Because the more time I spent trying to explicate my impulse to write that first sentence the way I had, and the more I listened to Juliana’s music—which occupies a not unremarkable portion of my hard drive’s real estate—on endless loops, and the more I read through some profiles of and interviews with Juliana for research—the majority of them godawful, shamelessly insulting, reeking of lookism—the closer I came to experiencing something like an epiphanic redirection in my thinking.

What I arrived at is this. When I was a manic-depressive teenager in a fundamentalist Catholic school, I couldn’t fully comprehend that there was not and never would there be a corresponding relationship between how much I venerated the musicians I found unquestionably excellent—like Juliana, like Fiona Apple, like Tori Amos—and my ability to convince anyone around me of their genius. It seems obvious to me now, and I cringe to think I ever harbored such haughtiness, but at 13 it was a source of ontological disjunct. I mean, I grew up surrounded by the vocabulary of worship, a lexicon of devotion to something and someone intangible. I was made to understand that devotion as something manipulable; something one could infect another with if given the chance. (If given the mission, I almost said, then said parenthetically.) I’d seen it for myself, in friends who sprouted wings as a restraint against impulse and allurement; catechized as much by scripture as by angst, as much by faith as by need. And yet there was no correlation when it came to the music I worshipped—which really did feel like scripture to me, and which I could prove, which I could provide, which needn’t have been taken on faith—and my ability to make acolytes of anyone I could sequester long enough to listen to just one song.

The necessary shattering of a delusion—here I think we are getting closer to what we mean when we say “underrated.” It’s a denotation of a desire’s disproportionality. It’s an arrow shot straight through the empty air of the chasm between what we believe to be unequivocally sublime and the failure of others to share that conviction. It’s shorthand for something I don’t believe we ever fully outgrow: the inconceivability that lies at the heart of the fact that a deeply-felt, unbridled enthusiasm does not always—or even often—endow one with the capacity to persuade others into its orbit. We cannot force into being a state of shared understanding or appreciation with another, no matter how indisputable the nature of something may appear to us. We cannot force it. All we can do is present the coordinates.

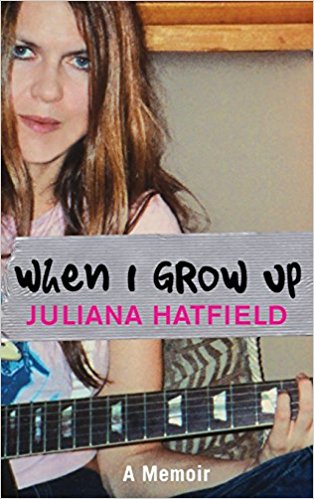

And it’s precisely this knot that I am coming to think of as the best embodiment of what it is about Juliana Hatfield’s work that’s so meaningful to me: its adamantine refusal to jettison the hope that one can make oneself understood in this world, even and especially when the dominance of one’s understanding of oneself is far from assured; even and especially when one’s sense of self is flickering with peripatetic feeling, full of contradictions and stochastic, diametrically opposed cravings; even and especially when one wishes to be understood by a public so often straightjacketed by an ineptitude for assimilating nuance and a press predisposed toward gossip and mythology and distorting what one says, what one puts out in the world—a pernicious and inexcusably ubiquitous modality of representation which, it’s no coincidence, is visited upon artists who happen to be women incommensurably compared to artists who happen to be men. “I wanted so much for my music—for my voice, and my words, and my feelings—to be heard, because I had been so desperately shy and so hidden and so mute and ineffectual for so long,” Hatfield writes in her memoir, When I Grow Up.

And it’s precisely this knot that I am coming to think of as the best embodiment of what it is about Juliana Hatfield’s work that’s so meaningful to me: its adamantine refusal to jettison the hope that one can make oneself understood in this world, even and especially when the dominance of one’s understanding of oneself is far from assured; even and especially when one’s sense of self is flickering with peripatetic feeling, full of contradictions and stochastic, diametrically opposed cravings; even and especially when one wishes to be understood by a public so often straightjacketed by an ineptitude for assimilating nuance and a press predisposed toward gossip and mythology and distorting what one says, what one puts out in the world—a pernicious and inexcusably ubiquitous modality of representation which, it’s no coincidence, is visited upon artists who happen to be women incommensurably compared to artists who happen to be men. “I wanted so much for my music—for my voice, and my words, and my feelings—to be heard, because I had been so desperately shy and so hidden and so mute and ineffectual for so long,” Hatfield writes in her memoir, When I Grow Up.

There is an undeniable radicality, then, in Hatfield’s determined readiness to share the results of her self-cartography—songs that adumbrate a human animal making its way through the world with the desire to be comprehended, recognized, and known on its own terms—in the face of the prevailing cultural creed that situates such a desire squarely in the realm of the juvenile, and which regards both the longing to feel less alone and the belief that one might produce something that would meaningfully satiate this longing in another as the mark of saccharine naïveté rather than a species of intimacy.

But here’s the thing: I want to feel less alone, and I’m not ashamed of that.

I want to be understood, and to understand. I want to know how—to paraphrase Amy Hempel—people are solving the problem of being alive. I want this now more than ever. I want, as a writer, to write something that might make someone else feel less alone; feel known, seen, understood. I want that now more than ever. And it’s demoralizing to see this desire—which seems to me the very essence of communication and of art-making, the most one can hope for and work toward—belittled and trivialized and written off as unsophisticated. (And if you think it isn’t, I’d ask you to consider the inescapable charges of “oversharing”—or the even more popular catch-all “narcissism”—that get lodged against anyone who seeks to make themselves legible in the so-called “culture of confession.”) I don’t want to feel an urge to subtilize or shroud my hope that art of any kind can make possible innumerable species of connection and catharsis. I don’t want to apologize for maintaining the belief that a willingness to authentically exteriorize the interior—to make the personal public—can engender a space somewhere between the two poles; a sustaining space that allows for fusion between people and topples preexisting modes and models of relationality that obscure, rather than showcase, the ways we are “for another, or, indeed, by virtue of another,” as Judith Butler has it.

From the time I first heard it 10 years ago, Juliana Hatfield’s music has been one of those sustaining spaces in my life. Her songs have been some of the most reliably edifying apertures in my life; steadfast companions in intervals of pain and pleasure and everything in between. They register the tectonics of fugitive feeling and imprecise thought while simultaneously dilating the surface area of each. How many times have I felt a knot go loose in me when listening to “Ugly”? How many times have I felt absolutely sundered by the end of “Choose Drugs,” only to replay it after the final chord? When I needed to drown out the noise of my cluttered, clanky, misbehaving mind, how loudly did I blare “Rats in the Attic” and “Ten Foot Pole”? When I was someone’s secret person, how often did I turn to “Sneaking Around” just to feel some sense of alliance with the speaker? And when, out of fear and everything behind the fear, I unceremoniously ended the first relationship in which I felt truly held, breaking my very own heart, wasn’t it “I’m Disappearing” that delivered some measure of comfort, giving language to what felt beyond language?

Which is to say that to listen to Juliana Hatfield’s catalog is to listen to and learn from someone gymnastisizing her way, with ardor and valor, through every unrelenting and unrepentant geometry: the mazes of habit and hurt; the confining latitude made by the lover who leaves; the lightless rooms where all one can do is appraise atoms of darkness; and the generous expanse that hope, when one finds it, opens up. Hers is a body of work admirable in its own right. It becomes infinitely more so when one takes into account just how willfully and menacingly the press worked to misunderstand, distort, and reduce her in the profiles and interviews of which I spoke earlier.

Here are just a handful of examples from an unfortunately abundant collection of possibilities:

- “Hatfield says she doesn’t care what other people think of her, but is clearly obsessed by her image…She seems to lie compulsively. Not exactly on purpose but rather like a self-obsessed child, because she is caught up in her own fantasies.”—Lisa Verrico, Vox (May, 1995)[1] Collis, Clark. “Review: Juliana Hatfield, Become What You Are.” Select Sept. 1993: n. pag. Web.

- “When the folks at Barbie start designing their autumn collection of slacker grrl clothing (‘She cooks! She cleans! She kind of, well, mooches about a lot!’) it’s hard to think of a more perfect role model than Juliana Hatfield.”—Clark Collis, in what is ostensibly a review of Become What You Are, Select (1993)

- Writing for Rolling Stone in September of 1993, Kim France tries to get Hatfield to agree to a notion she’s disavowed plenty: that her music and her lyrics are distinctly female. “I’m not doing this to advance the cause of women,” Hatfield says, and France calls these “strange words, coming as they do from a singer/songwriter whose 1992 solo debut, Hey Babe, pegged the loopy schizophrenia of being young and female with an almost scary accuracy.” She goes on to characterize Hey Babe as a record of “compelling self-involvement” and Hatfield herself as “the ultimate indie-rock, trust-fund kid, whose loose, ripped-at-the-seams T-shirts and baggy jeans she’s so fond of performing in only go so far to mask her good breeding.”[2]

- Angela Lewis, writing in March of 1995 for NME, notes that Hatfield is a difficult interview because she is “frustratingly oblique about her personal life.”[3]

- The lede for a piece called “Twee Will Rock You” (NME, Dec 93) asks, “Do dark, sordid secrets lurk beneath the squeaky-clean, virginal surface of Evan’s mate Juliana Hatfield, or is she just a Hatfield of hollow?”[4]

- In a cover feature for SPIN in March of 1994, Rob Sheffield spends a paragraph describing Hatfield’s “delicate petunia blossom” image, and later, when they’re out to dinner, he remarks, “I’m not her grandmother or anything, but it’s good to see her eat her pasta.”[5]

Regrettably, these excerpts constitute only the tip of the iceberg, and it’s a truth universally acknowledged that the hidden ice is what fucks up your boat. (There are more write-ups than I could possibly cite whose sole objectives were either invasive questioning about Hatfield’s virginity or sinister curiosity about the nature and parameters of Hatfield’s relationship with longtime friend and collaborator Evan Dando.)

It astonished me to read through the archive I amassed in my research, though I suppose it shouldn’t have; one can still turn to current publications and reliably find thoughtless and repugnant profiles of artists who happen to be women. How quick these writers are to garrote the possibility of something meaningful being communicated in favor of writing something easy and appealing to the limbic-brained. How habitually they shirk the task of writing about the music itself—about Hatfield’s virtuosic guitar playing, her skilled and singular grasp of prosody, her dynamic stage presence—in favor of eroticizing a personal life they feel an inexplicable entitlement to knowing the workings of, obscuring her very personhood in the process. How purposefully they discount or treat as suspicious anything Hatfield says—be it about her intention, her identity, her ambition, running her own record label—when it stands in stark contrast to their preconceptions about her; when it threatens to dismantle the image of a tortured “alterna-waif manqué with negligible talents,” as Hatfield offers, in a moment of self-deprecation in When I Grow Up.

It astonished me to read through the archive I amassed in my research, though I suppose it shouldn’t have; one can still turn to current publications and reliably find thoughtless and repugnant profiles of artists who happen to be women. How quick these writers are to garrote the possibility of something meaningful being communicated in favor of writing something easy and appealing to the limbic-brained. How habitually they shirk the task of writing about the music itself—about Hatfield’s virtuosic guitar playing, her skilled and singular grasp of prosody, her dynamic stage presence—in favor of eroticizing a personal life they feel an inexplicable entitlement to knowing the workings of, obscuring her very personhood in the process. How purposefully they discount or treat as suspicious anything Hatfield says—be it about her intention, her identity, her ambition, running her own record label—when it stands in stark contrast to their preconceptions about her; when it threatens to dismantle the image of a tortured “alterna-waif manqué with negligible talents,” as Hatfield offers, in a moment of self-deprecation in When I Grow Up.

It feels paramount to mention here that the overwhelming majority of these patronizing, belittling, insolent pieces of so-called journalism—both those that I’ve quoted above and those I compiled in my research—were written by men. These same men can be found, if one simply tracks their bylines, writing with tact and erudition about artists like Kurt Cobain, J Mascis, Ryan Adams, Paul Westerberg, and so on; artists whose music is very much in conversation with Hatfield’s. (Hatfield and Westerberg even formed a band together in 2016—The I Don’t Cares— and released the smart, untamed, rollicking album Wild Stab.) This is not to suggest that men can’t or shouldn’t write about female musicians—though it certainly wouldn’t be a mistake for music-oriented publications to make a more conscious effort to recruit the voices of women for their masthead—but rather to render more clearly the space from which Hatfield is singing and playing from for most of her career: the familiar fire of a crushing, enduring patriarchy all too eager to silence or else shellac its own narrative over women and their stories and their songs.

Nevertheless, she persists. Despite having to withstand such unimaginable bullshit over the course of three decades in the music business, Juliana Hatfield remains ever committed to writing songs of undiluted and unposed vulnerability, vested with the still-intact belief that—by way of fury, fun, raw intensity, stirring honesty, or something unnameable—she can still—she will still—create the conditions under which she might understand and under which she might be understood.

This is her radical audacity: even if her mouth is full of sutures, Juliana Hatfield finds some way to still and always be singing.

Thank god.

[1] Collis, Clark. “Review: Juliana Hatfield, Become What You Are.” Select Sept. 1993: n. pag. Web.

[2] France, Kim. “Becoming Juliana Hatfield.” Rolling Stone 30 Sept. 1993: n. pag. Web.

[3] Lewis, Angela. “Everything and the Grrl.” NME Mar. 1995: n. pag. Web.

[4] Cigarettes, Johnny. “Twee Will Rock You.” NME Dec. 1993: n. pag. Web.

[5] Sheffield, Rob. “Mystery Date.” SPIN Mar. 1994: n. pag. Web.

This post may contain affiliate links.