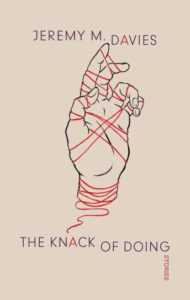

[David R. Godine; 2016]

The Knack of Doing, Jeremy M. Davies’s first collection of short fiction, is a master class in writing by constraint. The constraints are playful, as if Davies has posed a series of small challenges for himself — write a story by letter, by repetition, by list, by blurb. Davies delights in the unlikelihood of stories. That he can draw drama from unlikely forms and sources animates his writing. He has the defiant air of an escape artist, finding elaborate ways to constrict himself, then freeing himself with a flourish. These escapes are displays of his talent: his virtuosic language, his grammatical panache, his narrative dexterity.

Davies is quick to establish the rules for each story. In “Kurt Vonnegut and the Great Bordellos of the Danube Delta,” these rules are literal: Vonnegut’s eight rules for writing serve as the story’s scaffolding. The narrator composes a sort of essay-story as a response to Vonnegut. In “The Sinces,” each sentence begins, “Since you went away.” The sentences grow longer and more complex, taking on more emotional freight as the story progresses. “On the Furtiveness of Kurtz” is a six-part treatise on the fellow faculty member who ruins the narrator’s career and marriage. “Delete the Marquis,” told in competing numbered sequences, takes place in a carriage en route to a mesmerist’s estate. “The Dandy’s Garrote” is both a blurb for a friend’s book and a backhanded takedown. “The Terrible Riddles of Human Sexuality (Solved)” describes sixteen items, asking after each description, “What am I?” The story, about a fetish worker named May, emerges from the Q and A. For instance:

11. A tube of toothpaste, a toothbrush, a stapler, a jar of mayonnaise, three paper clips, a rubber bone, a pocket fan, a blindfold, three rolls of quarters, pancake mix, a nine-pin, two thousand dollars in cash, a Japanese radish, a water pistol, carpet samples in beige and white, fifty yards of twine, a yellow pad, a phone-book, a fountain pen, a brass alarm clock, a clown’s nose, a cowboy hat, fishnet stockings, a bottle of mineral water, a jump-rope, a square foot of Astroturf, a baguette, a nail-file, an inflatable flotation device, rubber gloves, felt gloves, three handkerchiefs, a false beard, a wig (blonde), a wig (white), a football, five refrigerator magnets with painted representations of classical composers, a slender vase, a box of Epsom salts, and a VHS copy of Lucille Ball in The Fuller Brush Girl (1950). What am I?

(Answer: The customer’s briefcase is full of strange shapes. May, on tiptoe, can’t keep from trying to see the combination he dials to open it.)

Davies revels in list-making, and here, a story formatted as a list of objects contains its own virtuosic object-list. The objects are familiar, mundane, but collected in the customer’s briefcase they become strange, even menacing. The customer takes on a vaguely sinister quality — as vague as his unidentifiable fetish. Davies is attracted to lists as an organizing rule, especially numbered ones. It’s easy to see why: enumeration forces the writer to operate in sequence, helps control the acceleration of the piece, and provides a channel for escalation. For a writer seeking a form of constraint, a numbered list is a pretty generative one. Both “Vonnegut” and “Riddles” are numbered, as are “On the Furtiveness of Kurtz” and “Delete the Marquis.” “Marquis” presents the three characters — the narrator, the fellow traveler, and the Marquis — in three numbered sequences, which begin to overlap as the narrator’s reality starts to fracture. The story is further formatted by indent variations, so that the narrowest account, that of the Marquis, occurs as quoted speech within the traveler’s account, in turn contained within the narrator’s. The three perspectives nest within each other. The numbered sequences, proof of the writer’s control, prove the narrator’s imprisonment.

Davies’s stories are energetically self-consciousness and self-scrutinizing. In “Vonnegut,” the rules for writing become a prompt for writing; as the narrator responds to and amends the rules, narrator and writer converge. In “Kurtz,” Kurtz gives the narrator storytelling tips, saying, “I hate . . . stories that begin with a pronoun.” In “Delete the Marquis,” the story gives itself, and the collection as a whole, a onceover:

I hastened to clarify to the man a point of rudimentary narrative logic that I felt had long since slipped through his inexpert authorial fingers, namely that there must be something at stake in order for a story to hold the interest of a reader or listener, and that his tale had already sacrificed all possibility of achieving this necessary tension with the introduction of the notion that there were no reliable incidences whatever in his fiction but only suppositions that could at a moment’s notice be overturned by the unbelievable character of the Marquis . . . such that, all in all, Victor was positing a world without rules and without consequences and so without, in a word, drama.

Davies does furnish his stories with traditional sources of “necessary tension” — there are dissolving relationships, estranged parents, even a manhunt. But the constraints, funneling the stories into unexpected channels, generate their own drama: will the writer be able to pull off these daring tricks? Is he insane? Can this really be the stuff of fiction?

Implausibly, against his self-imposed odds, Davies executes. Each tidily constructed story possesses its own logical rigor. Davies is an incredibly gifted writer whose stories contain wit, humor, and compassion — the stuff indeed. He is also a careful one — a sure-stepper. His constraints are parameters. He engages a sense of play, allows himself to enjoy the pleasures of language, but it’s a circumscribed play. In his attention to detail and design, he’s like a watchmaker — a compliment, as watches are nice and very hard to make. But in fiction, it’s more fun when the watch, after pages and pages of diligent ticking, explodes, starts screaming, or shoots poop out of its dial — does something, anything, to upend the pattern or upset the conceit. I longed for the fictive mechanisms to bust down their retaining walls — or at least to see more wobble and tremble. Enough tidiness, enough constraint. By the end of the collection, so constrained, I felt a sense of my own confinement; so confined, I could only admire the well-built prison walls for so long.

These stories reward re-reading, and each time I returned I sensed a stronger emotional presence, felt more acutely the plight of the narrator. Here is the father-narrator of “Ten Letters”: “And I, in my office, have become ashamed of my arrogance. I don’t know a thing about any of you. I don’t know a thing about the world.” Davies can call up a tender moment, but often his narrators possess an intelligence and erudition that can feel cold and clinical — of the mind and not the heart. It’s the narrative voice of the smartest person in the room, too smart for his own good, his gifts a torment. Davies exudes that Wallace-like quality: the intelligence with no off-switch, not even a dimmer. Davies’s fiction, like Wallace’s, shows that possessing such intelligence can be alienating, that an analytical mind can be self-consuming, and that the smartest people can be the biggest dopes. That is perhaps the emotional thesis of this collection: to be wary of, and certainly to pity, the intellect that precludes happiness. Davies’s narrators, a collection of misfits, pedants, and layabouts, are compelling voices, but difficult people. They are easy to listen to, hard to love. Yet that is what they long for. They’d even settle for not being alone.

Walker Rutter-Bowman is a fiction writer living in Syracuse, New York.

This post may contain affiliate links.