[Sidebrow; 2017]

[Sidebrow; 2017]

I’ll start with what little I know.

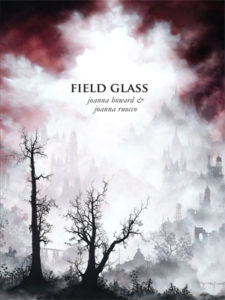

Field Glass is a 97-page book cowritten by Joanna Howard and Joanna Ruocco. It’s a collection of linked fragments, some as short as a few words, some as long as a page and a half. It’s written in what seem to be multiple first-person voices. Some entries are untitled. Others have headings: [outstream] appears above 23 fragments, [spool release] above another 10.

A field glass is a kind of binoculars. After I googled the phrase, the title Field Glass began to make sense to me. The book’s landscapes are both naturalistic and militaristic: the kind of thing you might look at through field glasses. And looking through the eyes (or visual appendages) of the characters, you feel that a significant distance has suddenly been erased, leaving you unnaturally close to something whose context you can’t fully access — a feeling liable to result from any encounter with technology that compresses space.

Several times Howard and Ruocco echo a line from René Char’s war journal, Leaves of Hypnos: “How do you hear me? I speak from so far . . .”

Well, as I read, I could make out the words, but I didn’t really get what was going on.

On the first page, for example, I understood that these lines were describing a war:

In that time, the houses were behind the hedgerows, beyond the trenches, obscured in the middle realm between the landings and the stations, that forest that was a town that was an outpost. Is it resistance if disguised as trees? When the forest exploded, there stood revealed a swarming mass of men. Then they stood no longer.

But I wasn’t sure who was fighting, or where, or when, or for what reason. Ninety-six pages later, I remain uncertain, but I have some theories.

Who was fighting?

There are “insurgents.” There are “deserters.” There is a “resistance.” There are 14 members of some kind of military, whose words appear under headings that seem to comprise their blood types and ID numbers.

The first of these soldiers’ testimonies appears on page 32. The author, 667Q15/O NEG, turns out to have been “the resident commissioner” and recounts a search for the “commander”:

I rolled over a hundred bodies, peeled back the lids, opened the mouths and checked the teeth against the records, filled pipettes. I couldn’t get a positive ID on all I sampled but none of it was his.

Whoever these people are, they are adept at ordering words. The language of 667Q15/O NEG, like all the sentences in Field Glass, has a pleasing rhythm, forming staccato clauses and parallel structures that feel like they’re accelerating, especially if you read them aloud. (“It moves like a fast thick river,” my husband said when I did.)

Some of the other 13 fighters use their tightly wound prose not only to narrate their past but also to launch aphoristic or otherwise philosophical reflections. “There are people, there are stories,” says 351R00/O POS, who seems to be a priest and is also identified as REV. “The people think they shape the stories, but the reverse is closer to the truth.”

Almost endlessly broad in its implications, this passage also narrows in on one of the book’s specific mechanisms. To a rare extent, the only things a reader knows about the people speaking in Field Glass are the stories they tell, and their ways of telling. These are bare narratives, shorn of conventional contextual markers. The speakers’ genders and names are not identified, their historical and geographical locations are obscure, they do not describe themselves. To you, the reader, the “characters” are shaped only by the point in their story where you encounter them.

Where?

The result is an atmosphere of transience, the kind one might find in any place where people don’t plan to stay for very long.

This ambient impermanency appears to have a specific cause. “Fact: uprootedness occurs, particularly in time of occupation,” says a voice in a section labeled “[outstream].” “And the urge is simply to uproot others. We are under the sign of silence, enemies lodged in neighboring chambers.” Rather than any particular spot on earth, the setting of Field Glass is simply this situation of occupation.

“Being occupied is being in a situation of absolute perversity,” said Paul Virilio, describing Nazi-occupied France in a 2010 Vice interview. “I was ten years old in 1942. I had to understand that the people who lived close by were my enemies, and the ones bombing me were my friends.” Howard and Ruocco describe something similar, but the stakes are not as clear. They write of enemies and friends, but you’re never sure who’s who. The fighting does not seem to advance any goal other than the perpetuation of conflict.

In this sense, their imagined “occupation territories” seem to fulfill the prediction Virilio made in Bunker Archeology, a 1975 study of Nazi bunkers that Howard and Ruocco cite in their acknowledgements. “From now on the military establishment will defend not so much the ‘national’ territory . . . as that of energy, the area of violence,” he writes, emphasis his.

In Field Glass, the area of violence is first of all an area of miscommunication:

As with any place of dwelling, those who inhabit it learn to navigate its passages in the dark. Among the collectives, transmissions resist. It would be, after all, foolish to seek some elegant, simple, and useful scientific theory of running that would embrace runs of salmon and runs in hosiery?

Howard and Ruocco suggest that communication breakdown — collectives living together in ignorance of each other’s meanings — is what draws lines between enemies. The residents of the occupation territories are also known as “the captives of misinformation.”

When?

The allusions to Virilio and Char give Field Glass a vague World War II aura, as do mentions of “shortwave broadcasts of fireside chats” listened to “on the rugs before the footed stove.” But the book — whose publisher identifies its subject as “a near-future war” — mixes the futuristic with the historical. People, for example, are able to live without blood, which has been spilled in quantities that saturate the land. “In the beginning, no one knew how to miss the feeling of that fluid movement, a sensation unperceived, but then they learned,” says one unheaded section.

Some priests contrive to formulate a replacement. And “this liquid, priced dear in its bag, with its coil of transparent tube, is fit for any valid person, all those who come with permits, paper monies, nostalgia for the living.”

Does this nostalgia pertain to specific loved ones or for anyone alive at all? Is the apocalypse over, in other words, or ongoing? It’s impossible to say. “One lives and thinks in a nefarious coil,” reads another unnamed fragment. “there is no progress, even time does not move forward in a straight line; it reappears in the same form.”

The idea of time as material with physical form recalls another line of Char’s — “time is couch grass; and man will become couch grass sperm” — as well as Ruocco’s novel Dan. Melba, that book’s heroine, conceives of time as a clear jelly that “kept changing its clearness, showing, for example, one Melba, then another, then another.” Meanwhile, she wonders, “people keep dying and where do they go in the jelly? Do they rot in the jelly and make more jelly? Could time be made of people?”

Like these reflections, the combination of advanced and rudimentary technology in Field Glass highlights the resemblance of time to Whac-a-Mole. The priests save time and effort by concocting a blood replacement suitable for everyone, but time and effort must now be expended on new, anachronistic requirements — permits, paper monies. So perhaps what seems to have been saved has only been displaced. The book takes place in a future that has resulted from a rearrangement of forms, not from forward movement.

For what reason?

As Virilio has observed, efforts to save time also cause slowdowns. Highways made it possible to drive quickly across the country, but they also created conditions ripe for traffic jams. The internet made it possible to instantaneously publish and distribute writing, but the resulting onslaught of information can take hours every day to deal with.

Howard and Ruocco use as an epigraph a passage in which Virilio highlights another possible effect of trying to increase speed by shrinking space. “’Eliminating distance kills,’ René Char once said,” Virilio writes, continuing,

When you endlessly increase the liberating power of the media, you bring what was once hidden by distance and the secret — which was distant and naturally foreign to each one of us — far too close; you run the risk of reinventing, here and now, some kind of barbarism (barbarous = foreigner; one who does not speak the language). In other words, you run the risk of inventing the enemy.

Viewed through the lens of these lines, Field Glass appears to embody Virilio’s idea. It depicts a world in which efforts to compress time and space have brought into contact groups who do not understand each other, and who have as a result become each other’s enemies.

This world, though, contains the seeds of an alternative possibility. In the act of describing it, Howard and Ruocco mimic its acceleration of time and elimination of distance — stringing together sentences you read rapidly and admire without having understood them; giving you a close-up view of scenes whose larger contexts are obscure. But what happened to me is not what happens to the enemies the book conjures. Reading the equivalent of secrets eloquently whispered in a language I didn’t know, I felt invited to consider them appreciatively.

Afterword: who wrote what?

I wondered when reading who had written each part, Joanna Howard or Joanna Ruocco. Wondering felt prurient, like asking whether a scene in a novel had happened in real life, too.

“The two of us wrote Field Glass together,” the authors say, pointedly not sharing any new information. “Since each of us was several, there was already quite a crowd.”

While it might not matter who wrote which word, the unanswered question helps propel the book forward. Field Glass sometimes reads like a series of volleys; other times it reads like an exquisite corpse. In the first instance, forms collide. In the second, their collision creates.

Megan Marz is a writer and editor living in Chicago.

This post may contain affiliate links.