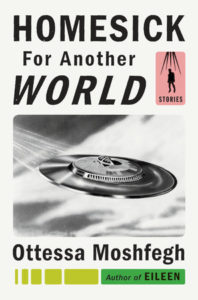

[Penguin Press; 2017]

[Penguin Press; 2017]

With Homesick for Another World, Ottessa Moshfegh was ready with the perfect title for a perfect book with which to enter 2017. The condition the title describes is not covetousness of another world: homesickness implies some claim on this other place, inherently disowning this one. This first collection of stories by Moshfegh, which have appeared in places like The Paris Review and The New Yorker between the publication of her first two books, hews to the queasy theme evoked by the title of the role of desire in disappointment. Disappointment borne of desire, disappointment where desire should be, disappointment wrung into desire: Moshfegh fixates on this churn through the course of fourteen stories featuring a few recurrent figures like douchebag actors, poison berries, and men who compare themselves to god.

The defining key in which Moshfegh writes is that moment one realizes their bright, fresh orange has shrugged into alarming white fuzz and gone black and weeping in their hand. In her short fiction, the natural way of rot and the evolutionary soundness of repulsion keep rising from and stubbing themselves on strains of desire, sometimes wily and spontaneous but mostly grimly mundane. That commitment makes Homesick for Another World nearly nauseating in one gulp, but that is not a bad thing: the sourest thing is recognizing how being let down has so much to do with oneself and the quality of one’s desire, how the sourness is compounded when one displaces that disappointment on the object of one’s desire, and how much black and weeping intimacy pools in the palm of that displacement.

We’re human, we’re fucked, how do we even love when the impulse yields nothing but disgusting spores because we’re breathing into the necks of garbage people: it’s 2017.

The richest spoils in this collection come from the story — so well named, again — “A Dark and Winding Road,” about a man fleeing marital conflict, who cannot escape into anything in a cabin in the woods. His narration goes: “It was deadly quiet up there. You could hear your own heart beating if you listened. I loved it, or at least I thought I ought to love it — I’ve never been very clear on that distinction.” There is one expression of the freedom he desires, a bottle of Château Cheval Blanc, and he has no way to uncork it. As he loafs around the cabin, he finds evidence his dirtbag brother has been using it, although he does not clarify how the discovery of a giant dildo enables him to reach this conclusion. When a friend of his brother shows up looking for crystal, she helps the narrator free himself from himself, uncorking him with the bottle of Château Cheval Blanc in the manner of a dildo. The dark the narrator edges toward is transposed with a light escapade up the ass. It is Moshfegh in excelsis.

With the advent of 2017, “An Honest Woman” has swerved from essential reading (“you should not deny yourself the experience of this story”) to urgent reading (“you have to read this whether you’d like it or not because it is vital to understanding this world”). At a wheezing pace, the story follows a puttering sixty-year-old man named Jeb as he inserts himself into the life of his younger, unnamed female neighbor. She goes about her days unaware he can hear her through the walls and he is listening intently:

He was glad the girl didn’t try to emulate the singer’s flourishes when she sang along. He would have been embarrassed to hear that. She sang a sad song — clearly she knew all the words — and in the rests he thought he detected the faint swish of a magazine. He imagined her sitting on a colorful quilt, yellow lamplight glazing her bare arms and glinting off the vertebrae of her neck as she peered down at the pictures of everything she coveted. He felt that he was getting to know the girl by the sounds she made — her foul mouth on the phone with her girlfriends, the violent slams of her bureau drawers as she dressed, her quick steps up and down the stairs in the morning, her slow steps up and down at night. Jeb had even heard her passing gas a few times, and he hoped one day to tell her so. “And yet my affection for you did not diminish,” he imagined saying. “In fact, it only endeared you to me more.”

After a mesmerizing, dread-filled episode of manipulation, which moves Jeb to dismiss his neighbor, the veneer peals back. She was incidental to the force of his desire; his disappointment with her has only augmented his real desire. The extent to which the final three lines of the story describe the condition of our world has only increased as of January 2017:

When it was over, he took off on foot down the road into town and spent the whole afternoon ambling like a stray dog under the striped storefront awnings, dodging the daylight, lest his white skin burn and blister. He licked a vanilla ice-cream cone and regarded his slumped silhouette in the shop windows. He straightened his posture as best he could, but he was stooped by nature. He could still be a god on earth, however, if only he found the right tribe. That would really be something — to be worshipped and beloved. Jeb whistled through the warm evening streets, imagining this wonderful new place and all the stupid people who would gasp and fall to their knees in ecstasy every time he shuffled past.

There is no other world for which readers can be homesick. We only have the one pocked with Jebs. That is why readers need Ottessa Moshfegh: to slip us the poison berries and get the shuddering and gagging out of our system so we can approach our desires for our home with fresh eyes.

This post may contain affiliate links.