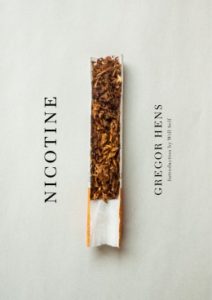

[Other Press; 2017]

[Other Press; 2017]

Tr. by Jen Calleja

It has been eleven months since I quit smoking cigarettes; eleven months and seven days. And I can honestly say I only think about smoking several times a day. The thought comes not as desire or longing, but as if the world before me fades and I dip into another reality, as if out of some silly science fiction television series, a reality in which I’d never quit smoking at all. As an example, while walking my dog this morning I realized I had just exhaled oddly, and that it had felt at once terrifying and familiar, as if I’d taken a long, leisurely drag on a Camel Light and let it loose, at first from my mouth and then, intentionally, through my nostrils, the better to savor the charred notes of the burnt tobacco’s flavor; and for a moment I actually tasted “cigarette” on the December air. I looked around to see if there were smokers nearby, but there were none; it was just a memory, a blip in my cognitive processes, a gentle reminder that no matter how long it has been, I am still an addict, and my addiction is still waiting to mug me.

The self-help industry would have me believe that this moment was a triumph. I did not succumb, and thus another blow was struck against the enemy, another brick laid in the wall against my weakness. And yet I’m inclined to agree with Gregor Hens, who describes his addiction in Nicotine as a fundamental part of his identity – as a person, as a writer – and so my brief relapse into the smoker’s state of mind, the mindful exhalation, the remembrance of exquisite flavor, was in effect a moment in which I returned to a truer version of myself. A version, it should be noted, that I’ve chosen to leave behind.

I suppose I belong to the final smoker’s generation; that is, the final generation of young men and women in the developed world who were born to be smokers. My mother smoked a cigarette a day during her pregnancy. The science was in, but the prohibitions against smoking while pregnant weren’t as strident as they should’ve been. In any case, that early exposure to nicotine is unlikely for the vast majority of American babies born today. It will likely be limited to poorer families, as smoking, like everything else in this country, has been divided by class lines, with the poorer and less educated bearing the brunt of its ravages. With high-minded policies like the ban on smoking in public housing, even the most vulnerable in our society may be spared a childhood like mine, in which I was constantly surrounded by the smoke produced by my mother and father, who each smoked two packs a day in our small apartment.

In one of the many wryly humorous passages in Hens’s book, he recalls the day-long car trips his family would take during the holidays, when his parents chain-smoked for the entire journey. The windows, naturally, were closed:

I know that already within the first half hour, in the Siebengebirge hills even, I would routinely feel ill. A couple of times, I can say with some assurance I had to throw up in some carpark or other. I’d be in a kind of trance by the time we reached Franconia, an intoxicated stupor I wouldn’t wake from until we reached Balderschwang – after thirty or more passively smoked cigarettes. Once the child safety lock was released I’d push open the door, shuffle out breathing stertorously with an overly acidic stomach, and stagger sleepy and thirsty and strangely excited towards the rented chalet.

This experience is quite familiar to me; the only reason it seems extreme is that my family didn’t do long car rides. But we did fly long distances, always in economy, always in the smoking section. I remember smoking cigarettes freely on solo flight when I was 16 (the international airlines were always so very cosmopolitan about youth smoking), and I considered it an indication that I’d grown up, which is a sign of how little I’d internalized the fact that I’d passively smoked thousands of cigarettes on flights as a child. The telling detail in the above passage is the child safety lock: Hens’s experience was, for all intents and purposes, a form of torture. It is absurd to think that millions of people used to pay for the privilege to be similarly tortured on flights.

Part of the pleasure of reading Hens’s book is these details, and the way they illustrate how his own life spans a pivotal moment in the history of tobacco. World War II was instrumental in creating a boom in the tobacco industry worldwide. My Japanese grandfather, when he was still alive, would recall his early days in the Imperial army fondly, in part because it was where, as he put it, he learned how to smoke for the first time – a sentiment I’ve also heard expressed by American vets. Whether you fought for liberation or for the subjugation of a hemisphere, nicotine was enjoyed equally. In Hens’s book that boom is made clear by, among other things, the monthly cigarette allowance his deceased aunt received as part of her pension payments; an allowance that will continue for the decedent’s family until 2071, 100 years after her pension began. Granted, she worked for a cigarette company, but the value inherent in cigarettes by 1971 is clear: almost everyone smoked them. Hens’s childhood is one that takes place amid a haze of cigarette smoke, and he lives long enough for that haze, almost globally, to clear.

While reading the book for the second or third time, I wondered how it would be received by a nonsmoker, how the many details that Hens gets just right – the practiced ease with which a smoker can handle cellophane wrapping of any kind, the snap of the wrist some smokers use to tear off and toss a filtered tip in one seamless motion – would appear to a nonsmoker’s eye; but then it occurred to me that there are people out there like my uncle, who has never smoked a cigarette in his life, but was nevertheless raised by an unrepentant smoker, one who kept smoking, despite lung cancer, until the day she died. Nicotine, in this sense, is a time capsule, one that serves not only to illustrate Hens’s conceit that cigarettes served as a fundamental building block to his identity, but also to show how cigarettes have been integral to post-war society as a whole. Everyone has been affected by cigarettes, whether we like it or not; they are a plague that it appears society will survive, and their widespread use is an anachronism that can, when framed correctly, inspire both revulsion and a strange sort of nostalgia for simpler, more awful times, such as when Hens recalls Taxi Driver: “How long’s a quickie? Listen, Mister, it’s your time, the young Jodie Foster says; fifteen minutes ain’t long . . . when that cigarette burns out your time is up.” Similarly, you may recall that iconic scene in Aliens, when a traumatized Sigourney Weaver’s neglected cigarette has burned down entirely, leaving a long finger of smouldering ash. Just as recently as the 1980s the idea of smoking in space seemed believable.

And yet, it can’t be denied that the book is an addiction memoir. It delves into the process of the author’s recovery, his relapses, his changes of heart; above all, it is a book about the author’s desire to change his habits, never mind that Hens frames it as a change in his identity. What is truly remarkable about Nicotine is that it is entertaining, and Hens manages the addiction narrative with uncommon wit and narrative energy, interspersing his memories with self-deprecatory stabs at pop science, psychology and philosophy. Yet hidden within the narrative are moments of true poignancy, such as the almost offhand way in which he chronicles his mother’s descent into depression, and his gradual alienation from his father’s affections.

For some insight into how this project could have gone awry, the reader need not look very far; the foreword to the book, written by Will Self (whose books Hens has frequently translated into German), is the quintessential example of the smoker as a bore. The key distinction between the two men is stated baldly: Self says, “there’s only one thing worse than not being able to smoke, and that’s not being able to talk about it”; Hens, on the other hand, says, “I’m also aware that it won’t be enough to talk about it. I have to relearn.” Self is still concerned only with pleasure; Hens seeks transformation. Never mind that Hens appears to fail, at least in my eyes; all of us addicts will inevitably fail, in some way or another. It is enough that he tries.

Sho Spaeth lives in New York.

This post may contain affiliate links.