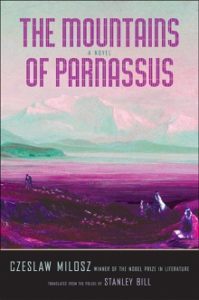

[Yale University Press; 2016]

[Yale University Press; 2016]

Tr. Stanley Bill

Do not be fooled by the cover’s claim that it encloses a novel: The Mountains of Parnassus should be read as poetry. Recovered from the files of Nobel laureate Czeslaw Milosz after his death, The Mountains of Parnassus was finished but never accepted by a publisher during Milosz’s long life. Devotedly translated from the original Polish into English by Stanley Bill, Milosz’s disorienting science fiction novel slips in and out of the mind’s grasp. Reach the end and admit you’ve no idea where you traveled or how you got there. But wander back through its sentences, and find how one after another deploys words with utter precision. As Milosz himself notes in the introduction to the text, the form of the novel evades him; in The Mountains of Parnassus, he seeks a new form of novel, one that neither plods forward with 19th century sensibilities as much SF does, nor disintegrates under its own scrutiny as happens to all too many postmodern projects. It might be better understood as a series of speculative prose poems that ask for the meditative wanders of a flâneur rather than dole out the quick action and hard-core descriptions stereotypical of the genre.

Milosz’s curious book strings together character studies of future humans, a few who live in a still drifting Earth and another who traverses time only to realize he’d rather fade away than live indefinitely among the now fully-detached elite. He gives up his life among the Astronauts upon determining that he “had lived superficially, but now the time had come for meditation and wandering, in the expectation that things always become clearer when we remove the screen, suddenly exposing ourselves to time, which dismantles us piece by piece, so that we might be prepared for an abrupt end” (116). This idea of “exposing” oneself to time, to “consent” to the “sands trickling through the hourglass” runs through the work, as Milosz explores a world of random violence, extreme inequity, and floundered imaginations. He mourns the loss of a reference point for humanity as what is so casually labeled “progress” speeds us beyond the Sun: “I wondered,” the former Astronaut shares, “whether man had strayed outside the circle inscribed by the very nature of his mind, whether he had lost his symbols, nourished in the earth and fed by the sun, moon, plants, and animals, so that our imagination didn’t turn there” (99-100). Milosz’s writing mourns the loss of mystery and its potential to foster wonder.

The philosophical strength of The Mountains of Parnassus amplifies as it moves from one story to the next, concluding in an appendix that depicts the dissolution of religion and art and the reformation of ritual. Milosz lingers in this final section; he muses over humanity’s increasing inability to believe in the divine — not for a lack of desire to believe, but for a lack of imagination. Milosz describes the multitudes of artists that proliferate in the postmodern age who print their “100,000 almost identical poems” every day and create a din “like an enormous hall filled with endless rows of pianos. Everybody was playing his own instrument, straining to drown out the others” and unable to hear more than a neighbor, even were he to pause his fingers and try to listen (124). The future Milosz presents is marked by hurried, empty excess. Meaning is ever harder to believe in.

And yet, there remains hope throughout his writing in the option of slowing down and returning to earth, as the Astronaut chooses to do. This choice is one that accepts death as one of the bounds that gives life significance and shape. In his introduction to the text, Milosz accepts the partiality and imperfection of his own production and hopes that “the reader’s imagination will receive no shortage of small stimuli, but also an expansive area in which it can freely glide — which perhaps is better than having everything spelled out and constrained by the twists and turns of the characters’ stories” (11). Indeed, it is a text that presents just enough information to raise questions about this speculative world but answers none of them. Although this sparseness induces confusion, even detachment on first reading the novel, it, like a poem, opens holes to consider upon meandering back through its prose.

The main sections’ hazy tone coupled with minimal world-building threaten to drown the reader in lassitude, but the introductory remarks convey Milosz as playful and personable, a compatriot who derides the “diabolical boredom emanating” from many contemporaries novels ‘tormented by structuralist theories,” which “seems hostile to the very vocation of narrative (6). Although written for its initial (unsuccessful) trip to the publisher in 1972, the introduction’s commentary on the state of the novel remains strikingly accurate. Indeed, perhaps the entire novel proves better suited to the current moment than to the one it was born out of 45 years ago. As life moves ever faster and mysteries are persistently revealed, Milosz’s unusual song amidst the roar of the pianos creates a necessary excuse to pause.

Emma Schneider is a graduate student at Tufts University. Her research focuses on North American and Environmental Literature.

This post may contain affiliate links.