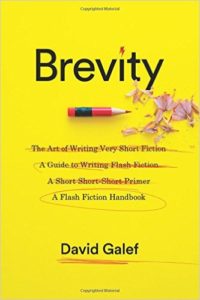

Like a good New Year’s resolution, flash fiction writers are forever promising to trim the fat. David Galef’s new book, Brevity: A Flash Fiction Handbook, lends some ideas to whip stories into a manageable, entertaining shape. And it provides no small amount of readerly delight. Brevity is a little book–a relief for those whose shelves sag with the combined weight of jumbo-sized anthologies–brimful with insights about the writing process, best practices, and fabulous selections for reading and rereading.

Andrew Mitchell Davenport: We have prurient readers. They like to snicker so I’ll throw them a bone: When it comes to flash fiction, does size matter? And, can one have an abiding relationship with a literary genre who consistently gets it over with within two minutes?

David Galef: Well, size sure matters if you have a limit of 1,000 words. And if this were a piece of nanofiction, I’d have to stop around now. But since you posed a freewheeling question that demands an equally upfront answer, let me say this: size determines a lot of things, but bigger isn’t always better. Put it this way: would you like to read a short story about a man obsessed with his cuticles or a novel on the same subject? Titillation alert: Or just an embarrassing scene in a public restroom, where almost no one ever sets a narrative? How about the moment right after a major public figure makes an absolutely asinine declaration? The point is that good flash fiction is appropriate to its length, whether it’s a vignette or a character sketch or a what-if premise carried to its logically absurd conclusion. What if your five-year-old niece started counting to infinity and said she wouldn’t stop until her parents got undivorced?

See, you’re awfully good at this prompt thing…I’ve just read your book, there’s a ton of fun prompts inside, and I really want to pose one to you. Any secrets behind thinking up a really good writing prompt?

Yes. Drink a lot of coffee. Be outrageous but logical, be provocative but not unreasonable, and shut the door against an easy exit. Example: How can these five disjointed items (missing car keys, adult pajamas with feet, naked mole rat, inside-out pizza box, purple Sharpie) be woven into a story? Reading a fair amount of fantasy and science fiction can also help.

Do you ever read a book and think, well, that could have been reduced by two-thirds?

For “ever,” substitute “often,” though usually it’s not so radical as a 66% cut. It’s often the ending, which goes on far after the reader gets it. I understand that the protagonist won’t be going back home this time. Or the setup, which takes 75 pages before the real action kicks in. Start with the baby’s abduction, not the adoption. I also find myself mentally editing an overlong dialogue (lose the five long pauses) and a backstory that’s not all pertinent (does it matter that she went to Cuba?). That might be one of the perils of my professions, which include editor, writer, and English professor. On the other hand, it’s amazing how many stories could use a good editor. Flash fiction is good that way: the built-in assumption is that every word counts.

How can you distinguish between a genuine piece of flash fiction and a sketch? Do you have an antenna for flash fiction?

That’s a good question, though it’s not confined to flash. One of Thomas Wolfe’s stories, really a novella, is called “A Portrait of Bascom Hawke,” and it’s more or less what it says it is, a character sketch. But that’s okay, and the same is true for a letter to a friend (or enemy) posing as a story, or a rant on some topic, or an anecdote. I even have a section in Brevity devoted to prose poems because a lot of them get published under the flash fiction banner. Lyric intensity and concentrated prose are fine for the form. If you had to pin me down, I’d say that a piece of flash fiction should display some narrative drive, some semblance of plot, or else why is it fiction? But a great deal can be submerged or hinted at. Give the reader a few apt suggestions about a character, and you know what she’s going to do the next time she sees her ex.

Say I’m a skeptic and friends have been trying to get me to read flash fiction for years, to no avail. Who should I be reading?

As opposed to flash fiction itself, the list is long. It’s also hard to pose names without insulting authors left off the list. Here are a few of the greats, even if their work often runs over the 1,500-word limit loosely applied to short-shorts: Jorge Luis Borges, Colette, Isaac Babel, and Saki. Recently I’ve been taken by the flash fiction of Len Kuntz and Meg Pokrass. Flash alert: George Saunders has a fine piece under 400 words called “Sticks” in Tenth of December. But bear in mind also that there’s a whole galaxy of flash fiction out there by now, and what sets off your lights will depend somewhat on what or whom you like in longer fiction.

Is the flash fiction writer’s attention span shorter than the average fiction writer’s?

What? Sorry, I was busy finishing up another piece of flash fiction. Really, I’d like to say that the length of a writer’s focus shouldn’t have to do with the duration of the work, but that’s not quite true. The British writer V. S. Pritchett, best known for his short stories but also the author of several novels, remarked that he didn’t think he had the vegetative temperament of a novelist. With short work, you don’t have to sustain your attention month after month, sometimes for a combined duration of years. Longer writing generally takes longer. Briefer writing allows more short-term gratification. In fact, after a while, a flash fictioneer may start to think of her life in terms of brief scenes: the company cafeteria at noon when the new intern ate a sandwich and bag of potato chips with chopsticks—wouldn’t that make a good piece of flash fiction?

I suppose it would. Do you ever say this piece of flash fiction is too short?

Been known to happen. Mostly when the piece needs some unpacking that the writer, not the reader, has to perform: missing backstory or character development, for instance. How are we supposed to know from the thumbnail presentation of Rhonda that she’s an astute judge of human behavior, despite her three failed marriages? On the other hand, that six-word encapsulation apocryphally ascribed to Hemingway, “For sale: baby shoes, never worn” could be even shorter: “Sale: unworn baby shoes.” Hmm, maybe not.

You write that “timing, economy, and precision are crucial.” I wish my friends would read your book. Their stories take up too much of my time.

You could get some new friends, but I don’t think that’s necessary. Instead, you might recommend edits and hope that doesn’t lose you some friends. In fact, timing, economy, and precision are desirable in all sorts of activities, from tennis-playing to stand-up comedy, not just writing flash fiction. But I do bemoan the lack of good editing these days, and I mean that even for fine writers. The problem you mention, writers whose work doesn’t sit right, is also partly a matter of not considering the audience. In this age of instant publishing gratification and people uploading to their peeps, the old general reader barely exists anymore. Nothing wrong with a broad appeal to a large swath of the reading public.

You’ve taught a lot of creative writing workshops. They make me visibly sweat. You ever see a student come in dragging her feet and leave with a passion for the craft?

You mean because workshops seem so labor-intensive, when writing ought to be inspired and carefree? Hmm. But yes, some workshop participants seem a little reluctant at first. They usually light up when they hit on a topic or situation that excites them, like a street scene that happened yesterday or a fantasy come to life. They do a good job and want to do that again. Of course, more satisfying is someone who already has a passion for words, which drives the whole enterprise. A writer like that can make a shopping trip seem illuminating.

Andrew Mitchell Davenport is an editor of Full Stop.

This post may contain affiliate links.