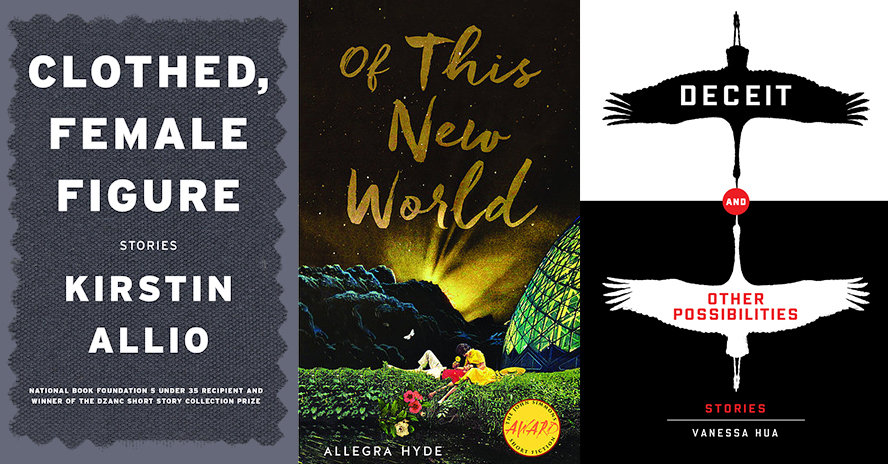

Kirstin Allio, Clothed, Female Figure [Dzanc Books; 2016]

Allegra Hyde, Of This New World [University of Iowa Press; 2016]

Vanessa Hua, Deceit and Other Possibilities [Willow Books; 2016]

1. On Book Reviews

A few weeks ago, I went to the movies and watched a very strange film (it ended with Colin Farrell’s character about to — maybe? — blind himself in an act of faith and love. Or idiocy. Or something). Maybe you’re like me, and you also like to read critical responses to things, especially challenging things, especially after you’ve seen the things themselves: after seeing the film, I read a piece of writing disguised as a review of the film. The text, though, read more like a lofty demonstration of the author’s vast knowledge of Samuel Beckett. Huh, I thought.

Was the film itself properly reviewed? What does this mean, ‘properly reviewed’? What is contained in a proper film review? Considerations of the actors’ performances? The mood, the pacing? The cinematography, the sound, the structure, the tone? The meaning? The import, the imagination, the ambition?

I think so.

Were these things discussed in the review I read? Not really.

An equivalent effort would, here in this review of Vanessa Hua’s Deceit and Other Possibilities, Allegra Hyde’s Of This New World, and Kirstin Allio’s Clothed, Female Figure, three new prize-winning debut story collections, feature my going on about the New York Mets’ lost season, how they’ve been beset by injury and a historic failure to perform in the clutch (bad luck: see Of This New World), the strange karmic resonance of two autobiographies by ’86 Mets heroes (oh, what once was: see Clothed, Female Figure), and, worst of all, signing players with violent and/or antisocial tendencies (Deceit and Other Possibilities) . . . while along the way also sort of discussing the story collections themselves.

Reviews are strange animals, of course, even when Beckett and the Mets aren’t invoked. They’re often written by friends of authors (admission 1: I’ve reviewed friends’ books, and positively; admission 2: I know Vanessa Hua and am ‘friends’ with both her and Allegra Hyde on Facebook, though I’ve never met Allegra Hyde. Kirstin Allio is a stranger to me). Sometimes young writers are told: You there, You should write reviews, it’s a great way to be published! Sometimes reviews are solicited: hey, You, want to review this book? And depending on You’s busyness, ambition, fame, competitiveness, guilt, whatever, the book is (or isn’t) reviewed. When it is, that review is written in all manner of contexts. Punches may be pulled. Swings, swung. Authority may be diminished — or established. Or both. Innovation in the review itself might be treasured: write a cool review, You! Who cares about the book You’re reviewing! Establish Yourself!

Far too often book reviews reveal less about the texts under discussion and more about the critic (see our Beckett lover, and, certainly to this point, your current author). Worse, they rarely consider the craft of writing. Instead, they’re a fuzz of complex context — motives are vague, assertions are vague, so much is foggy and unclear, and does it all really add up to a simple tag line that can be slapped upon a book jacket?

So I’m going to try to contextualize this review as much as I can. At AWP this year, I felt guilty for not being a good literary citizen, so I assigned myself the task of writing a book review, which ballooned to a trifecta of three forthcoming books — books I could pretty easily get my hands on. I read each slowly, patiently, with little distraction.

Further context: this time, my goals as a reviewer. Usually when I undertake a book review, I hope to learn a little something and, in the review, show what I’ve learned; maybe, for other interested writers, I might even assert a little something about the craft of fiction. And I certainly want to be respectful to the authors under review; I’m an author, and as such, I can tell you that mean-spirited criticism doesn’t help me, and it certainly doesn’t help the project of literature. Well-meant criticism, though? Sure, absolutely.

And you. Obviously I want to give you the gist of the book. So you know what it’s like. And mainly I want you to finish the review thinking things like, Hm, maybe I should read that book, or Maybe I won’t read it, but at least I have a clear sense of it!

(And, most important of all, Wow, that guy knows a lot about the New York Mets!)

2. Three Quick Summaries

Kirsten Allio’s Clothed, Female Figure features ten stories spread over 263 pages. The point of view characters are women, generally in their twenties and thirties. In “Clothed, Female Figure,” a nanny recalls both a precocious past charge and a sorrowful long lost secret, while in “Quetzal,” a grad TA negotiates her feelings toward one of her students while suffering fraught childhood memories of her mother. The emphasis on the past in each of these stories is true to the collection as a whole, as Allio’s protagonists almost always are weighed down by problems of the past: mothers, employers, friends, and enemies.

Allio’s writerly concerns are less plot and ‘real world issues’ than they are mood, and language, and internal conflict. Keen attention is paid to metaphorical turns of phrase, as in, again, “Clothed, Female Figure”: “Leah, age six, occupied the bedroom, with a ceiling as yellowed and cracked as heirloom china. She wore frocks that twisted around her pencil body and her ears pushed through her hair like snouts.” Such vivid description appears by the page. The stories’ situational contexts are doled out slowly, almost stubbornly so, as Allio quickly immerses the reader into fraught worlds with little interest in defining those worlds to us; this authorial withholding functions as an interesting substitute for tension. Throughout, characterization — usually attended to more in the main characters while lesser characters orbit hazily — is dense, and the protagonists, while often one- or two-note are deeply, or entirely, defined (or consumed) by that note.

There is a fair amount of drinking done. Often quietly, and alone.

Vanessa Hua’s Deceit and Other Possibilities also has ten stories, and at a page count about half as long as Allio’s, Hua’s works are almost breathless at times, concerned more with plotted events that lead to large climaxes than lingering on the aftermath of what has happened.

In “For What They Shared,” we follow Lin, a Chinese national living in the US with her husband Sang. Both are engineers. Lin likes life in the US and doesn’t want to return to what she sees as an oppressive China; Lin and Sang have taken Lin’s parents camping, to show how great it is to live in the US. Unfortunately, nearby rowdy campers begin to ruin the serene trip; one of these campers is a Chinese-American, Aileen, who is stuck between camping with her (white) fiancé’s friends, feeling sensitive to Lin’s obvious plight, and fretting over a pregnancy she hasn’t yet revealed. The situation escalates into conflict and, literally, conflagration.

“For What They Shared” exemplifies much of the collection: most stories are third-person and often feature main characters with chips on their shoulders, characters who, though they try to do right, eventually make deeply flawed — and often violent — decisions. “For What They Shared” also shows Hua’s general thematic concerns: tensions arising from disparities in income, race, and other social issues (a gay son comes out to his parents, a Mexican immigrant boy tries to make sense of his parents’ struggles, a church group tries to do good works in Kenya). Throughout, parental pressures weigh heavily, as do expectations of wealth, social status, and happiness.

In Allegra Hyde’s Of This New World, we move faster yet: thirteen stories in 130 pages. Hyde’s interests tend toward the slipstream and the conceptual; these are the most ‘contemporary’ of the three collections and also the weirdest. Amongst the far-ranging situations we find ourselves in are Eve and Adam camping out post-garden-expulsion, an attempted settlement of Mars (narrated by a man frustrated that he can’t get an erection), a commune survivor trying to adjust to ‘real’ life, a failed attempt at an ecological mission in Eleuthera, and a story about Charles Lane, erstwhile friend of the Alcott family (these latter two call Jim Shepherd to mind).

At times the stories can be clipped, aiming for flat humor, as in “Free Love”: “Precisely,” said the lawyer. “It’s niiiiiiineteen-eighty-three. No one has the patience for this hippie business anymore.” At other times the prose is brightly designed, as in the opening to “Shark Fishing”: “ . . . by those who outswam the drowning tug of hosiery and buckled boots, the swift darkness in a throatful of brine, who felt the soft footing of a sandy shore.” Tone veers greatly throughout, but each story is singular and wed to outlandishness of the situation. Women are most often the main characters, and thematically, there is a Vonneguttian unease with social institutions and bureaucracy, which Hyde plays as much for laughter as she does for sorrow.

3. Quiz: Which Book is Right for You?

Scoring rules: count your points for each answer, whether or not you agree (1), disagree (2), don’t understand or don’t give a shit (3).

- Yelp is the best way to find good Chinese food.

- The X-Files was a stupid TV show.

- Traveling to Iceland does not at all interest me.

- On occasion, I flip people off in traffic.

- It drives me a little bit crazy when my plans go awry.

- Perseverance is more important than wit.

- Dogs are better than cats, but cat YouTube videos are better than dog YouTube videos.

- Institutions are less interesting than family dynamics.

- I’m proud of my alma mater.

- There is nothing funny about Donald Trump.

If you scored . . .

. . . 10-16: read Deceit and Other Possibilities!

. . . 16-23: read Of This New World!

. . . 24-30: read Clothed, Female Figure!

4. Blurbs

“The stories in Kirsten Allio’s Clothed, Female Figure rise and fall like the slow inhalations and exhalations of a sleeping silent winter storm: ominous, weighty, and hushed. Outside, beyond the window, the world is distillate, ornately frozen into precise and shimmering detail . . . while inside, drowsily awake, we shiver and try to wrap the blanket closer. These aren’t stories of mood — they’re chamber pieces, lush and lonely, of a single serious mind.”

— Sean Bernard

“Deceit and Other Possibilities, by Vanessa Hua, is a shattered mirror reflecting to us the broken face of our contemporary world. Here we have the upraked muck of the American dream and, more importantly, those American dreamers who’ve finally woken to realize that their dreams don’t exist, at least not for them. Their reactions are what we wish our own could be: they’re pissed off and they aren’t afraid to show it.”

— Sean Bernard

“Allegra’s Hyde’s Of This New World is a sunshine hippie flower-girl just woken up to discover that she’s stuck in the grime of reality . . . and, worse, the world has turned into a carnival-cum-museum of the bizarre, dusty, and sad-but-true. There’s plenty of bright attitude in these stories, but unlike the brooding hipster at the back of the gastrobrewwhiskery, they also show the heft and depth of an emerging literary mind.”

— Sean Bernard

5. The End

Save the lies, everything I’ve written to this point is the truth. Here’s another.

Many of us read in so many ways, for so many reasons. I frequently read as a teacher: to inspire ambition in student authors, to understand what they’re trying to do, to help them better get to that place. Sometimes I read published works as an editor: to find works that ought to see print because of their uniqueness, their intelligent craftiness. And mostly I read as a fellow writer, looking to learn and to be dazzled, the latter happening when magic is made out of words, out of the mind, and even out of the awfulness of life, on levels grand and mundane.

And more than all that, going many years back to what made me love reading — to find a work that makes my skin tingle, that gives me the sudden floating feeling of having my own strange and quiet solitary humanity resonate with the words, thoughts, and feelings of another person. Mind and soul reaching out across time and space. It’s rare and wonderful to find such human resonance, to discover an authorial mind that is sincere (if strange), complex (if direct), wondrous (if severe and disheartened). The three writers who evoke this feeling in me most of all are Nabokov (not for Pale Fire or Lolita), Bolaño, and Berlin.

Of course it’s unfair to compare anyone to these three writers.

For the moment, let’s be unfair.

All three collections under review here skew more toward promise than toward realization: all three authors are talented, invested in the literary world, but at the same time, all three could use more control. For her part, Kirstin Allio’s gorgeous metaphorical language is deployed at random; it isn’t used as consistently as it could be to highlight key moments, to linger in the thicker passages. Structurally, Vanessa Hua tends to rely on factual backstory to the point that at times the present story loses momentum, and the pacing becomes a halting back-and-forth. Allegra Hyde, while conceptually wonderful, isn’t yet doing as frequently as she could the harder work of realizing her strange worlds: while they’ve fire within, they’re more gaseous clouds than burning stars.

Hyde’s interest in the conceptual concerns me as a general trend in contemporary fiction. Much contemporary work seems crafted toward being the loudest piece, the signal through the noise: who can devise the biggest flash, the strangest and most colorful situation, never mind the human truth often left behind, unattended. And all three collections here, all very much first-person and/or written in present-tense, often end with a resolution of external circumstances, satisfied with merely the implied impact of the events that have occurred. These stories are swirls of thought (Allio) or event (Hua, Hyde), but the impact of what has happens on the characters is too often nebulous at best — it is a rumor of the fall, rather than the realization.

When I read the best of Bolaño, Berlin, Nabokov, their urgency — their sincerity, their investment, the deep faith and belief in what they’re writing — is unmistakable. Language to them is more than decorative. They take on the troubles of reality for a reason — to do more than capture moments of distress; their strange worlds are built in painstaking detail; and the people who live in those worlds are left deeply and profoundly impacted. And that’s the thing, that’s what these writers are aiming for — the profound. Based on the promise of their debut collections, the three authors under review here demonstrate a clear capability for the same, and I very much look forward to seeing that promise realized.

Sean Bernard’s fiction has appeared in numerous journals, most recently in The Common, Crazyhorse, and Western Humanities Review. His debut novel, Studies in the Hereafter, was published in 2015; in 2014, his collection Desert sonorous was awarded the Juniper Prize in fiction. He teaches creative writing at the University of La Verne.

This post may contain affiliate links.