Most of us, when asked what we would give in order to end our suffering, would say: anything — everything — a school full of children; a single diamond ring, under duress. Roger Reeves says, “I give my tongue,” and then he gives it, like a man of his word, “to any man’s altar” in the hopes of bringing God down to tend to the wounded and the suffering; or, if not God, then Walt Whitman, “the Wound Dresser.” In his kletic poem of Whitman (where kletic is invocatory — classical — the sort of poem written by Sappho) Reeves calls upon the poet to speak again about the body, which Reeves renders truly grotesque, not electric. This is 2009, the year that “Kletic of Walt Whitman, the Wound Dresser” appeared in Best New Poets, and there’s no cause for celebration, beyond the fact of this poem’s existence. It falls broken on the page, its fractured, italicized columns seeming like a dismembered body cut to fit inside a jeweler’s tiny drawers. Walt Whitman, the poem asks, can you dress this wound?

Most of us, when asked what we would give in order to end our suffering, would say: anything — everything — a school full of children; a single diamond ring, under duress. Roger Reeves says, “I give my tongue,” and then he gives it, like a man of his word, “to any man’s altar” in the hopes of bringing God down to tend to the wounded and the suffering; or, if not God, then Walt Whitman, “the Wound Dresser.” In his kletic poem of Whitman (where kletic is invocatory — classical — the sort of poem written by Sappho) Reeves calls upon the poet to speak again about the body, which Reeves renders truly grotesque, not electric. This is 2009, the year that “Kletic of Walt Whitman, the Wound Dresser” appeared in Best New Poets, and there’s no cause for celebration, beyond the fact of this poem’s existence. It falls broken on the page, its fractured, italicized columns seeming like a dismembered body cut to fit inside a jeweler’s tiny drawers. Walt Whitman, the poem asks, can you dress this wound?

To understand the suffering at work here, one must look to the history that informs Reeves’ book. He establishes it early, in “Cross Country,” when he writes, “When I ran, it rained niggers.” Thus he refers the reader to an entire racial history we have become familiar with, in time: slavery, and segregation, and lynchings, and hate. In language as mournful as it is brazen, the poem’s speaker, here assumed to be Reeves, speaking of his life’s experiences, implores his readers to understand, in his own words, “the making and unmaking/ of my body.” That is: the way African-Americans, or rather, their identities, are constructed and reconstructed by historical upheavals, injustice, and race — just the fact of their race. When your identity has been constructed for you, Reeves argues, the body becomes a kind of locus for all your suffering, its joints, muscles, and meat becoming in the reader’s mind fallible, malleable, a way to be destroyed: the black body subjected to violence, both the reason and the receptacle. There’s the black boy in Baton Rouge preparing to become a ghost, as thirteen black kids desegregate a Louisiana school in 1963 — this is what history has done to them.

It’s important to remember that King Me (published in 2013 and collecting poems of the previous ten years) predates the tragic, unnecessary deaths of Michael Brown, Freddie Gray, Sandra Bland and Eric Garner and that it was released just four months after George Zimmerman was acquitted of the murder of seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin. Black Lives Matter as a movement and as a call to action didn’t exist when Reeves wrote this book, but the philosophy behind it, and the long history of racial profiling and police brutality that informs it, acted as both the inspiration for and subject of many poems in King Me, including “Cross Country.” This poem functions like a list of places where the speaker sees his racial history in the world, in the “squawk/ and clatter of a hen” and “a body falling toward a horizon,” until finally his list is redefined not as the speaker’s vision of America but as America itself “speaking in translation,” using the racial epithet — “nigger” — to create a racist society that has adopted language as a form of violence. In this way Reeves is both attempting to reclaim the word as an African-American speaking out against racism and injustice and lamenting the fact that this word has already colored his life’s experience, making the natural world a place of great beauty and even greater horror where no one can enjoy “the blue/ hour of a field once wet” without also thinking of the strange fruit hanging from the trees and of a boy who is “running through a city that is running out of water.” No matter where we run, Reeves implies, racism will already be there. It’s part of the very soil of America.

In investigating the intersections of race and identity, Reeves unearths a vision of a black body as rooted in nature as it is in history. His poems are populated with mosquitoes that might be lovers, maggots that feast on corpses, and men slipping between the legs of a river. When Reeves writes, with startling eloquence, of the “body necromancing/ its own shadow” and then another’s shadow and of a mouth pulling water from behind a knee, his meaning is clear: he lives in a world where, in spite of and because of racism, African-Americans learn early how to transmute their pain into something beautiful; a world where their bodies decay faster than the bodies of others, and where death is as inevitable as it is, at times, erotic. In his most romantic poem, “Romanticism (the Blue Keats),” Reeves intones for his lover all his wants and desires, including a persimmon, a painting of a persimmon, the body’s burden, and — his final wish — “the dying that makes us possible.” His idea is that we wouldn’t be who we are without an expiration date, that death makes life beautiful in that same way rotting meat makes fresh meat more desirable. In his poems, readers find a kind of ugly luminance, vividly depicted by the “diamonds and mud of [his] mouth” and the “pink salt and eyelashes” of the woman he loves (referring no doubt to the crystalline sparkle of certain eye shadows). It’s this melding of poetic insight with the themes of racism and identity that gives this book its power.

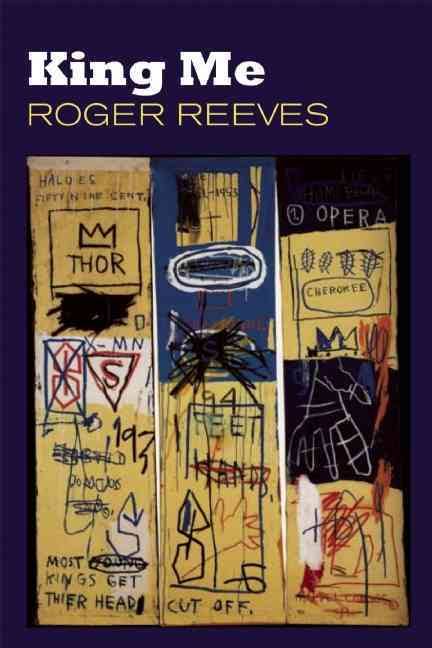

Reeves isn’t shy about saying he speaks for his people. The book is in fact dedicated to them, and the title — King Me — boldly announces the arrival of a major talent, a poet who, in 2013, not only saw the publication of his first poetry collection with Copper Canyon Press but also won an NEA grant, a Pushcart Prize, and on the strength of this success was selected as the 2014-2015 Hodder Fellow at Princeton before going on to win the 2015 Whiting Award. Reeves has, in no uncertain terms, lived up his title and become new literary royalty, the kind of poet who can and will speak for his people. But that speech is not without complications. When he writes, “I give my tongue,” he doles out “a single, scarlet lash — ” (a wound he wants redressed). His tongue, his poetic voice, becomes itself a source of pain, a place where the Pentecostal Church without its “usual ladder of tongues” meets the tongue of a parched man begging for water meets a small parasitic crustacean that attaches itself to the tongues of spotted rose snappers and replaces them. In this way, tongues becomes dangerous and questionable things, inciting us to ask, “Who will speak for this flesh“? If the tongue is a parasite, and if the body is dying, if “the self” is in fact the site of a complex racial identity constructed in part by its oppressors, then who’s speaking: the black body in its suffering or the forces that make it suffer, and therefore make it sing?

The answer, as it happens, is in Reeves himself. In November of 2015, while reading at the Hugo House in Seattle, the poet read a selection of new poems, one of which was inspired by the poet’s church days. It required him to speak in tongues, as a preacher or a believer might. In a rhythmic, incantatory voice, he explored the themes of race and violence and music, until, in the final lines, when Reeves’ tone became stark, and angry, and tired of musicality, he asked, “How much longer can I make black suffering eloquent?” It isn’t a question of time or ability, because Roger Reeves will always be brilliant, and, if history is to be believed, there will always be black suffering. No, it’s a matter of strength: how much longer will he be able to make black suffering eloquent? How much longer will he have it in him to do it? Strength then becomes both the question and answer. When Reeves asks who speaks for this flesh, the most logical response is, “Who’s the strongest?” And so, we must be strong, lest the forces that cause black suffering overcome us. Let us hope in the end that they don’t behead the king.

This post may contain affiliate links.