[Future Tense Books; 2016]

[Future Tense Books; 2016]

Before New Yorkers adopted Birkenstock sandals, there existed a very different Oregon: a quiet, working-class state trying to move beyond its logging days, a state that was of little interest to the rest of the United States since One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. But suddenly, Oregon catapulted into cultural relevancy. The “hipster” weaseled its way into popular lexicon, and we all became familiar with the sounds of The Shins. A migratory path had emerged from Williamsburg straight to the Alberta Arts District in Northeast. Fred Armisen and Carrie Brownstein declared: “the dream of the ‘90s is alive in Portland.”

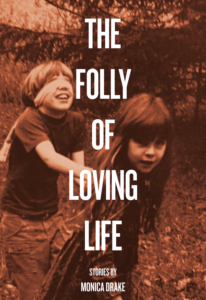

With The Folly of Loving Life, Monica Drake attempts to capture this shift in relevancy and illustrate the Oregonians that Portlandia left behind. In the formal style of Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteridge, Drake’s Folly is composed of interconnected stories that span roughly 50 years. Focusing on sisters Vanessa and Lu and the characters surrounding them, Folly aims to catalog the demographic transformation of Portland.

Despite its relatively contained scope, Folly is too ambitious in relation to Drake’s control of language. Implied in “transformation” is a before and after, but with Folly, Drake does not quite present either, as her weak imagery makes it inconceivable to elicit a sense of Portland. For a project so rooted in setting, the writing is heavy on description yet lacking in imagery: kitchens are “outdated but comfortable, with adorable wood counters,” and the fertile Oregon land expressed with a simple allusion to Mt. Hood. The writing is sloppy, filled with redundancies feigning melody. In one of the opening stories, “The Arboretum,” Drake describes the old house that Vanessa and Lu’s family move into as a “forgotten place, nearly abandoned.”

The stock-like characters are equally difficult to inhabit. “The Arboretum” centers on Baysie and Colin, Vanessa and Lu’s parents, and the rapid decline of their marriage after buying a house slightly outside of Portland. The house as it turns out, is quite spooky; its sinister qualities described through predictable markers of creepiness like poles that read “K-I-L” trailing off “as though whoever wrote it had fallen” and mysterious radios that only Baysie hears. Of course, when Baysie confides in Colin, expressing her anxieties about the “haunted” house, he refuses to listen to her. Eventually, in other stories, we learn from her daughters that Baysie spends the rest of her life in and out of psychiatric treatment. Drake employs Baysie’s mental break and absence from her daughters’ lives to establish that Vanessa and Lu are Deep because they are Troubled. The indicators and actions of their tortured lives are timeworn: Baysie and Colin are absent, so Vanessa runs away. Lu laments Vanessa’s leaving and her lonely existence by sleeping with men twice her age. Their friends have substance abuse problems, tattoos, and don’t believe in love—all tropes of the “Tortured” that Drake fails to complicate and renew.

Perhaps part of the reason the characters seem hollow is that their respective narrative voices never demonstrate change. In “Miss America Has a Plan,” a twenty-something Vanessa traveling through Central America sounds the same as 38-year-old Vanessa with a Master’s in Critical Theory in “S.T.D. Demon.” Vanessa’s voice doesn’t mature; she comes across as a horny young woman grasping desperately at sexual maturity and depth no matter her age: “My knees went wobbly, my spine hot: the baddest of bad boys, hotter than a stoned hockey player. Yes, I have a weakness,” and “I envisioned myself down on one knee in that taco shack, saying make me your fifth [wife], fill out that hand, count your mistakes and me among them.” Lu’s character also suffers, as she perpetually inhabits a surly teenager who feels entitled to “depth.” This emotional stuntedness of the protagonists does not seem purposeful — just exhausting.

Like the characters, we do not see Portland grow and change. Drake desperately wants us to know that hipsters have colonized, but we cannot lament loss without knowing what we’ve lost. Drake’s collection has been released by an independent Oregon publisher (Future Tense), perhaps suggesting that Folly is for the Oregonian who experienced “pre-cool” Portland. The Oregonian who would never confuse the Oregon Country Fair with a “county fair,” who can hearken back to weeks and weeks dedicated to studying Lewis and Clark (which, to Drake’s credit, she references in a moment of pure Oregon-ness). However, even this Oregonian would find themselves unable to recognize Drake’s Portland. Vanessa is prone to statements like, “I knew what people did all over this city when they found a line: join in. The best brunch spots had long lines” and “Instead of a driveway, we had a pod of food trucks taking up that slim space.” The obviousness of these grievances comes off as forced jabs at a Portland only recognizable by name.

Although Drake fails to render a large-scale Portland, she excels in moments of minutia. In “See You Later, Fry-O-Lator,” Drake paints the monotony of being a teen working part-time in fast food. Though the characterization issues and repetitive language hold true in this story, the imagery is evocative: “She slammed a handful of frozen meat patties against the steel edge of a machine to break the stack apart. Her sausage fingers, taut and red, were reflected more times than I could count in the stainless steel.” In “The First Normal Man,” Drake shifts the focus to Sean, Lu’s short-lived college love interest. Years have passed and Sean returns as a security guard at the Portland Art Museum. Sean paces the exhibits, imagining himself as art for entertainment and savoring any form of sound available in a silent gallery: “the ghost of my own white shirt floats over [the artifacts] as a reflection in the glass. My blue blazer shows up like a dark pool. It truncates the white in that reflection, as though somebody cut off my arms, and either side of my chest. Half a man, I think, and give my reflection a title” and “On weekdays, guard work is a quiet, isolated business. Every sound is as good as a conversation.”

In these contained moments, Drake indicates that she is capable of expressive writing, approaching the Portland she wishes to revive — the Portland that looked to Seattle as its more elegant older sister, the Portland that was capable of suffering suburban discontent. At this point in American literature the tale of suburban discontent — Mary Gaitskill, Jonathan Franzen, Jeffrey Eugenides — is as familiar as suburbia itself. In using this narrative as a window into discussing Portland’s changing demographic and economy, Drake positions suburban malaise in a fresh manner. However, Drake’s images are only ever evocative rather than grounding. By not firmly placing the reader in pre-twee Portland, the stakes of maintaining the memory of “uncool Portland” become as lost as the memory itself.

Julia Irion Martins is an editorial assistant at The Village Voice. Follow her on Twitter @juliairion.

This post may contain affiliate links.