Fiction and nonfiction, poetry and prose, criticism and literature. Books, like any other product, move faster when you label them. But books aren’t like any other product. Some writers feel neither desire nor obligation to create work that fits into market-tested categories. So they create other things. In Reality Hunger, his 2010 “manifesto,” David Shields celebrates an “as-yet-unstated” artistic movement defined by “plasticity of form” and “a blurring (to the point of invisibility) of any distinction between fiction and nonfiction.”

Publishers still need to label books, though, and readers still need words to describe what they’re reading. So the “movement” Shields identifies is stated all the time, at least in book reviews and the jacket copy from which they often take their cues. As the writer Maggie Nelson recently observed, “‘blurring boundaries’ has become its own sort of commodity,” even though “writers crossing genres — either within pieces or over the course of a career — is about the least new thing under the sun.”

The terms people use to praise Nelson’s work — hybrid, uncategorizable, genre-defying — prove her point. They belong to a newer set of labels that we use to praise work for not adhering to older labels. In doing so, we bind discussions of newness in literature to the categories we’re supposedly abandoning.

Bhanu Kapil points the way, or a way, forward. The author of several books, Kapil is another writer known for hybridity. In a recent roundtable published on the website of the Believer magazine, the writer Jenny Zhang said that Kapil’s work made her want “to use the term ‘hybrid,’ as fuzzy and undefined as it is,” for “the first time in my reading life.”

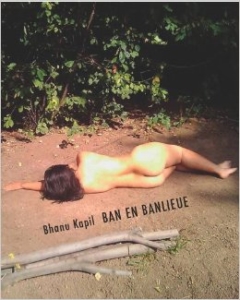

The roundtable was convened to celebrate the release of Kapil’s fifth full-length work, Ban en Banlieue, published earlier this year by Nightboat Books. Like the rest of Kapil’s books, and the word often used to describe them, Ban en Banlieue is difficult to define. But its concerns are clear. It is a book about boundaries—such as those around books, bodies, and nations—that are fundamental to contemporary writing, life, and death.

Rather than blur or ignore the lines other people have drawn around each other and each other’s art, Kapil remakes the map. As Nightboat’s publicist, Dustin Kurtz, aptly tweeted, “How do books work? How do bodies work? I thought I knew until Ban en Banlieue.”

Much of Ban en Banlieue tells the story of Ban, a girl growing up on the outskirts of London, “a black girl in an era when, in solidarity, Caribbean and Asian Brits self-defined as black. A black (brown) girl encountered in the earliest hour of a race riot, or what will become one by nightfall. . . . Ban is nine. Ban is seven. Ban is ten. Ban is a girl walking home from school just as a protest stars to escalate.”

Fictional and not, Ban is more than a single person: “I was writing an ‘intense autobiography,’” Kapil says near the book’s end. “Yes, my childhood nickname was BAN.” But the protest is specifically and historically real: “April 23rd, 1979: by morning, anti-Nazi campaigner, Blair Peach, will be dead.” Peach was killed — witnesses described police beating him with batons — in a protest against the British National Front, a white supremacist political party holding its annual meeting Southall, “a London suburb in which it would be rare — nauseating — to see a white face.” On the day of the protest, Ban hears glass breaking. Unsure whether the sound is coming from the street or her home, she instinctively, self-protectively lies down. After the riot, she “is crumpled like a tulip: there. A wetness, that is, with limbs.”

In addition to those of Ban and Blair Peach, Kapil invokes the true story of Jyoti Singh Pandey, a woman who was gang raped and killed in New Delhi in 2012. One way she tells all of these stories is by documenting the performances and memorials she undertakes for those who died:

Body outline on ground ringed by candles/flowers at the site where Jyoti Singh Pandey lay for 40 minutes in December 2012, raped then thrown from the bus and gutted with a steel pipe. I walk—naked, barefoot, red—from the cinema in South Delhi where she watched the Life of Pi. Then caught a bus. To this spot. The anti-rape protestors make a circle around my body when I lie down.

Again and again, Ban en Banlieue draws such outlines and circles around bodies real and symbolic. “Some of the work,” Kapil explains, “is set in the outlying, wooded regions of Greater London, where King Henry VIII had his hunting grounds. As a girl, I would lie down in my coat and trousers in the snow upon an embankment of earth: engineered, centuries before, to keep the meat in.” While one outline preserved the memory of a woman whose body was murderously violated, the other corralled animals for slaughter.

One of the book’s central conflicts is that between these dual functions of the boundary, a form both protective and destructive, sometimes at once. The bounded form of a nation, for example, might be said to protect some people while harming many others. Kapil’s fourth full-length book, Schizophrene (2011), traces the ways migration across national and cultural borders can cause mental illness: the ways the space you have penetrated can penetrate you so deeply as to splinter your mind.

Ban suggests that a person born within a national boundary but not fully defined by it might suffer a similar fate. “Ban is not an immigrant; she is a shape or bodily outline that’s familiar: yet inaccurate: to what the thing is,” Kapil writes. “. . . As a black person or child born to immigrants in the U.K. of 1971 — her birth broke something.” Ultimately, though, Ban’s body is what breaks, or shuts down; she is a victim of the effort to define the border of Englishness as racial.

To emphasize the destruction that national and racial borders can wreak on a person, Kapil frequently represents harm to a human body as the transgression of its borders by an oppressive or alien culture. In many “immigrant” narratives, characters’ life stories are defined and circumscribed by, primarily, the borders of the country they’ve entered. Identifying as an emigrant, Kapil rejects this formula, shedding the limitations that come with the identification of a person in the terms of a nation that brands her as foreign. “Immigrants don’t write many novels,” she writes. “Only emigrants do.” In Ban en Banlieue, she recounts life stories that are defined and circumscribed by, first and foremost, the boundaries of people’s bodies. (Conceptions of) nation, race, and gender invade these boundaries, not the other way around. “To summarize, I don’t want to have sex ever again in my life,” she writes. “I don’t want it if it means partnering with a white man. . . . Why would a person get naked for a person with whom you do not share a culture?” This is a deft inversion of racist complaints that immigrants endanger nations — analogous, in context, to the rarely challenged idea that a country should protect its borders.

By prioritizing the boundaries of the human body, Kapil recenters it. “Ban was waiting for me,” she writes, “in the darkness of the border, no long proximal but centered.” It makes sense, then, that the body of Ban en Banlieue is an exercise in recentering. Virtually every chapter takes the name of a section usually confined to a book’s front or back matter: Contents, End-Notes, Appendix, Dedication, Epigraphs, Notes. As a result, the material most readers probably skip is unavoidable. That which is usually at the edges, playing a supporting role, is the thing itself. This formal choice — redrawing the boundary of a book from the inside out — mirrors Kapil’s political aim of “re-imagin[ing] the boundary.”

Kapil has often equated the form of a book with the form of a body. In the acknowledgements that close her 2009 book Humanimal, about two girls raised by wolves in 1910s Bengal, she thanks her publishers for “conversations in passing towards a body forming itself in time, which is a book.” In Ban en Banlieue, she reverses this equation: “The form is the body — in the most generic way I could possibly use that word.”

If for Kapil the body is a book, its gestures and excretions are a language. In one of many descriptions of Ban lying down—or of lying down for Ban—“She folds to the ground. This is syntax.” In another, particularly vivid, description, “Genital life gives way to bubbles, the notebook of the body’s two eyes.” Kapil writes, “I wanted to write a book that was like lying down.” She writes, “I want a literature that is not made from literature.”

So she writes with her body. In “End-Notes,” a chapter of acknowledgements that ingeniously make other people’s contributions a central part of the book, Kapil thanks the poet CAConrad. Conrad is known for devising somatic exercises that involve undertaking activities for the purpose of writing about and/or during them. In from Conrad’s blog, a poet and a painter are instructed to “meet in the middle of the street to embrace and dance the Foxtrot with the painter leading, then switching with the poet leading,” then “return to write and paint within view of one another.”

While this exercise addresses the relatively inconsequential standoff Conrad imagines between painters and poets, Ban en Banlieue addresses more deadly conflicts rooted in nation, race, and gender. The technique, though, is similar. Kapil writes Ban and Banlieue during and about performances and other actions she undertakes for the purpose of “incubating” the book. She repeatedly lies down for Ban, for Jyoti Singh Pandey. After a memorial ritual during which Kapil pours red powder onto the ground where Pandey lay after the rape, peacock ore — a gift from Conrad — vibrates in her palm. Her first draft is bodily.

A gap remains between word and flesh. (“I wanted to study what happens to bodies at the limit of their particular life,” Kapil writes. “There was never a way to do this in writing.”) But the act of tracing that boundary puts them on the same plane, establishing a new relation between them.

Words and bodies also come into new relation on the internet, where people are constantly doing things to write about them or while writing about them. In Tao Lin’s Taipei, which the writer Frank Guan called “the first novel to successfully assimilate to literary art the mutant sensibility” of the internet, four characters are about to see a movie for the purpose of live tweeting it when one of them makes a verbal observation. “You should tweet it, stop talking about it,” his friend responds.

Yes, seeking experience in order to write about it is, like crossing genres, anything but new. But some kinds of internet art are defined by real-time (self-)documentation, or at least the illusion of it. This is why books made from blogs so often seem inert, like a commemorative program you might buy to remember a live show or a heavy exhibition catalog you’d lug out of a museum gift shop. Ultimately they’re a way to remember having lived through the real thing.

Kapil, who drafted much of Ban en Banlieue on her blog, is alert to this danger. “Thank you to the readers of my blog, Was Jack Kerouac A Punjabi?” she writes.

I incubated Ban under your gaze. In a public notebook. Thank you for reading. I was writing for you. You know the truth. You know that I am not really a writer. You know that putting Ban in this form is like wearing a three piece suit in the hot springs. I wish I had the courage to let the blog be my book instead.

By dissociating herself even from the title of writer, she suggests that the blog is less a piece of writing than a performance-in-words (the mirror image of writing-with-gesture). The bounded form of her book is inhospitable to this. It allows her to partially incorporate, but never fully replicate, what she incubated with her body and on her blog.

Instead of trying to efface the form, though, Kapil plays it up by foregrounding the paratext. For while the book constrains her work, it also affords her a striking method of recentering. This dual function mimics the contradictory properties of the boundaries Kapil traces around nations and human bodies.

Her focus on the forms of the book, the body, and the nation directs our attention toward boundaries that constrict and enable people — including writers — in material ways. These boundaries are not as easily blurred as the long-collapsed ones separating fiction and nonfiction, novel and memoir, poetry and prose (all terms, incidentally, that one might use to describe Ban en Banlieue). The forms they contain aren’t labels or sets of arbitrary rules but concrete constraints. To escape them, or reshape them, or put them to use, a writer must butt up against the physical world in addition to, or instead of, the lines separating literary genres. Ban en Banlieue thus redefines what a hybrid book might be: not one that contains both truth and fiction (what novel doesn’t?) but one that combines elements of print and internet, writing and performance, language a person can make with her larynx and language she makes with her limbs.

Megan Marz lives in Chicago and has written about books for The Point, Emily Books, and In These Times, among other outlets.

This post may contain affiliate links.