“To my dearest father this attempt is affectionately inscribed” reads a touching dedication in the frontispiece of a rare book. The page is a cyanotype print of the most vibrant blue, and the lines of white hand-written words are those of early naturalist and photographer Anna Atkins.

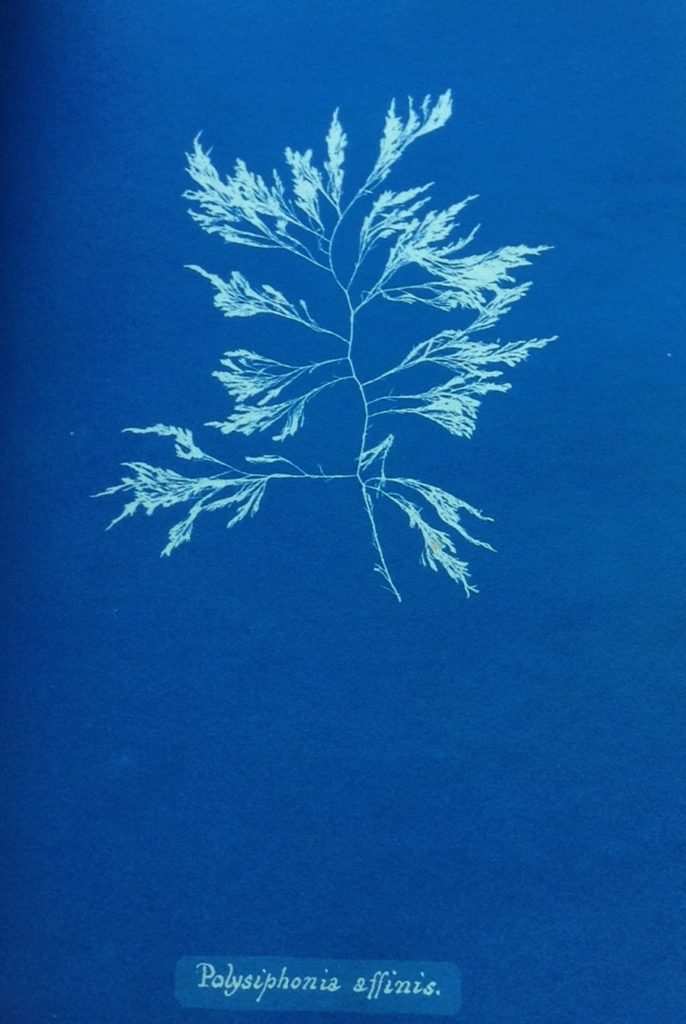

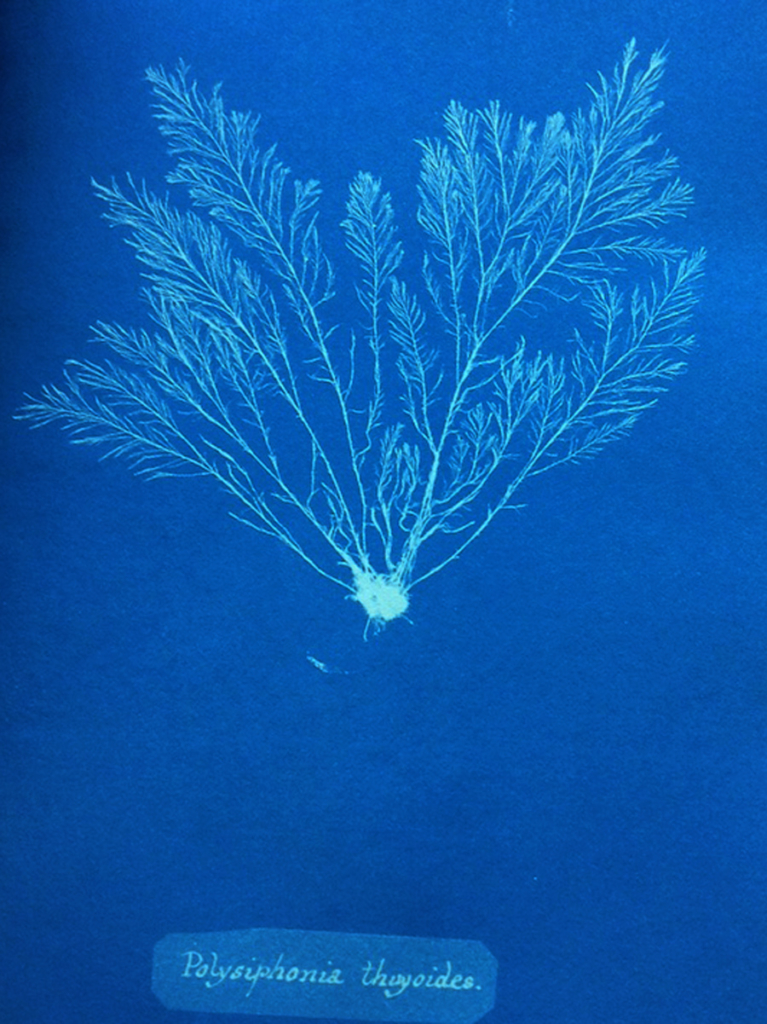

Several lifetimes older than myself, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions is thought to be the first book to feature photographic images. In 1841, William Harvey had published another first of its kind, A Manual of British Marine Algae. It was a survey of British algae which, although the most comprehensive thus far, included no illustrative content, relying only on written descriptions of the specimens it classified. Using the breakthrough medium of the cyanotype print, Atkins sought to address this visual lack of definition by illustrating her own botanical collection, identifying and recording hundreds of species of seaweed, a distinctly uncooperative botanical subject. Considered a pioneer by many, her contemporary relevance has been somewhat undermined by the fact that she is relatively unknown, a mere footnote in the history books of botany and photography.

I first came to Atkins’ cyanotypes in preparation for Bloom, an exhibition at the Horniman Museum, a museum of anthropology and natural history in the south London suburb of Forest Hill. Optimistic in others’ research, I imagined her obscurity to be a problem of retrieval, and that archives I didn’t know of yet were waiting somewhere, full of the answers to my questions about her work and the person behind it.

I held open the pages of the Horniman copy, each image more stunningly beautiful than the last, studying the cyanotypes for many more hours than I’d planned, having already postponed one lunch date. In the stillness of the library archives, these images are especially absorbing, as countless admirers of her cyanotypes will have noticed. I lose all sense of time looking at white silhouettes surrounded by azure blue which conjure the weightlessness of clouds in blue skies or the tidal rhythm of seafoam washed ashore. Atkins’ “sun-prints”, though magical in appearance and mythical in museological narrative, succeed in capturing a great deal of the intricacies and differences in form of the dried seaweeds she’d set out to record and classify — wispy fronds, fat strips, bubbly strings.

They appear fragile, but Horniman librarian Helen Williamson assures me of the cyanotypes’ hardiness. It is a conservational gift, I’m told, that contact with UV rays of daylight or the acid from skin won’t harm these artifacts. In fact, cyanotypes that suffer fading after overexposure to light will regenerate their color when returned to a darkened environment.

Despite these reassurances, I regard the book as if it were a living thing, taking care not to ruffle its pages or press too firmly on its spine.

The copy I am looking at is particularly unique, currently estimated to be the most complete of all to have survived. Bound into Volume 1 (of two parts), Volume 2 and Volume 3, and with a total of 457 plates including title pages, all of which are cyanotypes too, the folios arrived as part of the original 1901 Horniman bequest. Although accessioned, cataloged and kept in fine condition ever since, it wasn’t until 2011, when Williamson began researching the original collection of Frederick Horniman, that the nature of its rarity came to light.

For Bloom, the Horniman Museum presents its copy of Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, alongside works by British contemporary artist Edward Chell. Car parts ornately etched with unruly weeds and wildflowers share a vitrine with fossilized ammonites and willow pattern china from the Horniman collections. Overlooking this display are a series of forty gesso panels depicting studies of plants in and around the museum’s grounds and archives. Chell has been researching plant life in the museum’s official and tended gardens and archives, and also discovering what thrives on the pathways and perimeters, beyond the care of the museum’s horticultural custodianship. For each day of the show, a page of Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions is turned to display the prints to new and public audiences. In re-enactment of Atkins’ own botanical wanderings, Chell’s work emphasizes a growing urgency in how we feel about place and what we notice in our immediate surroundings, and how this influences thinking around broader issues of ecological and cultural conservation.

As we face an accelerating environmental crisis in this century, Atkins’ seaweed impressions surface with something like visionary timing, having slipped their privately-published moorings, to remind us about extinctions past and present, those erasures and absences yet to come. Today’s algal blooms are overstimulated by excessive UV light, suffocating other aquatic life, a tangible and local indication of the large-scale detriment caused by a climate change which is not only out of sight for some, but out of mind too. That algae is still such a classificatory conundrum, distinctions in algaeological taxonomy to this day still of much debate, Atkins’ initial experiments using seaweed specimens are symbols of mutability.

Edward Chell’s previous work with the less-observed or in-between has seen him use plants, landscapes and habitats, neither wild nor cultivated — such as “edgelands”, “managed” woodlands, and motorway verges — to think about how often that which is overlooked or difficult to classify reveals an understated value, more so after the fact of its loss. At the height of summer, one might anticipate Chell’s treatment of these plants to be a celebration of pulsing chlorophyll and lively color. Instead, his plant ‘portraits’ are inky blue, almost blackened, or phantasmagorically pale in others. They are reminiscent of cyanotypes, of course, but they also recall the blue and white patterns of Wedgewood’s Jasperware and 18th & 19th century decorative arts and crafts, trades which flourished as the newly prosperous middle-class began to display social and economic status through expressions of “taste” within the home.

Before the advent of photography, however, the use of the silhouette had been synonymous with portraiture, serving to keep the memories of loved ones freshly in mind, in the form of lockets and mementos. I am reminded of another book with similar concerns: Eclipse, which formed part of Chell’s 2012 exhibition of the same name. An elegiac study of roadside weeds and wildflowers, again cast in silhouette, it was at once a botanist’s field guide and an artist’s book, made in the spirit of both purpose and joy.

What is clear is that whether we arrive at the value of Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions as artwork, bookwork, scientific document or museological artifact, it demonstrates the hierarchical classification of others while resisting its own.

However Atkins conceived of her work, it was nevertheless both of, and ahead of, its time. Excursions to the coastline in search of ‘ocean flowers’ became popular among middle-class women of the late 19th century and Atkins was by no means unusual for her interest in botany. The specificity of her circumstances most certainly contributed to the possibility of this project and Atkins benefited from a proximity to scientific circles, learning informally through these connections.

Even so, Atkins embarked on what was, for a woman of her era, a highly ambitious and important project without formal education or professional validation. While women were beginning to have some presence within the sciences, women were still strongly discouraged from communicating their ideas in public spaces. Yet Atkins likely existed within an atmosphere of more socially progressive influences.

Anna Atkins was born in 1799 to a wealthy family living in the Kent countryside, not far from the coast. She was raised by her father, John George Children, who was widowed while Atkins was young, and as such they developed an extraordinarily close bond fortified by a shared appreciation of science.

Atkins would often help her father in his work, using her technical drawing skills in the two hundred detailed illustrations she contributed towards his translation of Lamarck’s Genera of Shells in 1823. Like his father before him, Children was a respected scientist with wide-ranging interests that included astronomy, chemistry and zoology. He gained particular acclaim from his contemporaries in 1813, when he built a large voltaic battery, and leading names in chemistry flocked to see a demonstration of its properties. Children was Eton-schooled and Cambridge-educated, a fellow of and later the secretary of the Royal Society, with numerous institutional affiliations, including the British Museum, Natural History Museum, and the Botanical Society (exceptional for its inclusion of women as full members from the outset — Anna was herself a member).

* * *

Permanence and definition had eluded the pioneering chemists of proto-photography during the early 1800s. Until William Henry Fox Talbot’s announcement of the paper-based process he called “photogenic drawing” (or drawings made with light) in 1839, and subsequently, Sir John William Frederich Herschel’s introduction of hyposulfite of soda as a fixing solution for silver-based processes in the same year, experiments with early photographic images had been as disappointingly ephemeral as they were laborious. In the wake of a frenzied race between Louis Daguerre and Fox Talbot to publicly announce and patent their inventions, Herschel presented a paper titled “On the Action of the Rays of the Solar Spectrum on Vegetable Colours, and on some new Photographic Processes” to the Royal Society of London in 1842.

It is unlikely that Anna Atkins would have been there to hear Herschel’s presentation to the Royal Society, but we may assume that she’d have heard about the technique from her father, if not with direct instruction from Herschel himself, since the Atkins and Herschel families were reportedly close.[1]

Atkins had continued to add to her botanical collections after she and her husband, John Pelly Atkins, married and moved to Halstead Place in Sevenoaks. But it was with access to the Childrens’ laboratory back at Ferox Hall, the family home — and with what must have been the exhilarating influence of science’s foremost thinkers — that she had everything in place to experiment so freely with Herschel’s cyanotype process.

The cyanotype process itself involved applying a chemical solution containing iron and potassium to paper. Once dried, specimens could then be placed on top. Left to expose in sunlight, the paper turned deep blue, leaving only the white silhouetted shape of the seaweed. The result was a light-fast image “fixed” by water, a form described by its edges.

Within just a year of Herschel’s paper, in 1843, Atkins had begun to produce copies of Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. This brief yet noteworthy timescale suggests enormous drive and investment of hours to advance the understanding and appreciation of a subject that clearly fascinated her — yet about the specifics of Atkins’ process and relationship with her work we can only conjecture.

Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions is an extremely rare book, with less than twenty copies accounted for, and so too is archival material relating to Atkins’ biography or intentions for the work. The clarity of profile that we expect from history’s great (and male) pioneers is missing, a scarcity first noticed by Larry J. Schaaf in his authoritative account of Atkins, Sun Gardens: Victorian Photograms by Anna Atkins in 1986. He notes that it “is a great pity that most of the personal papers of Anna Atkins have perished, for, in common with most women of past centuries, she is underrepresented in official records.” An archival lack disintegrates all hopes for a conclusive reading of Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions.

Like those before me, and maybe even Atkins herself, when I look skywards, clouds take on the likeness of fern fronds or strands of seaweed. Seeing meaningful shapes in clouds is a delight of daydreaming and child’s play, but when we stare into the range of ghostly absences left in the form of the cyanotype print, what emerges from them, all these years later and with nothing to go on? Frustrated by the archive’s failure to yield clarification, it is precisely this unresolved, unknowable quality that makes the cyanotypes ripe for projection or interpretation in place of such cravings. Without such certainties, it is the hints and touches like the typography Atkins fashioned into shape from the seaweed itself or the annotations she included to facilitate a more thorough understanding of the specimens that come to the fore.

No two copies of British Algae are exactly alike. This is partially because the task of binding was left up to recipients, with most copies having been rebound several times, but the cyanotypes are far less uniform than one might anticipate, from the variation in tones of blue to the crispness of the image. Atkins made thousands of cyanotypes, often issuing replacement plates if she later discovered what she considered to be superior specimen. While the total number of recipients was known only to Atkins herself, as was usual for private publishing of the period, Photographs of British Algae was issued in parts over ten years, gifted to friends and family. However, many of these people happened to be key scientific figures, including Herschel and Fox Talbot, founding fathers of photography.[2]

Larry Schaaf mentions in Sun Gardens that Atkins did not seek publicity, that most of her work had been left to private hands or stored in botanical archives under “AA”, signifying “Anonymous Amateur”. Copies of British Algae did find their way to scientific societies and institutions such as the Royal Society and the British Museum, though, presumably through Children’s affiliations if not by Atkins’ own doing. An inscription in another volume, “from Mrs. Atkins, with Mr. Children’s kind regards,” has led Schaaf to conclude that it was probably Children, rather than Anna Atkins herself, who was the point of contact with the majority of recipients, no doubt a father proud of his daughter’s “attempts” to see what she could do using a completely new technology.

Even considering the mannered inflection of Victorian address, the pedagogical nature revealed in the sentiment of Atkins’ dedication to her father feels rather exposed. With this tone of affect in an otherwise intellectual project, these cyanotypes take on the aura of a love letter, written not only to mark a father-daughter relationship, but written to the pleasures of shared discovery and learning.

As historians such as Ann B. Schteir have discussed, Victorian culture produced other distinctions too, pitching botanical specimen collecting as moral and “polite” amusement for women, against the more substantial and serious male study of botanical sciences. By the 1830s, botany was a contested space in which the voices of women were starting to gain prominence. Yet, it was women’s “amateur” involvement, from field work in locating specimens for male experts to popular writing on the subject, which seemed to problematize and trivialize those very same contributions.

A similar historical precedent for the display of moral respectability through domestic containment is found in still life and flower painting, a genre which had acquired a feminized reputation as the parlor pursuit of respectable ladies. Female artists were commonly tutored by brothers and fathers, painting the wildflowers gathered on chaperoned walks. These didactic, paternalistic concerns for safeguarding moral value as educational and social capital within the family were still active in mid-19th century society. In the long shadow of the slave trade and with the unresolved “problem” of the poor in post-industrial revolution Britain,[3] Victorian obsessions with moral duty, sanitization and progress migrated away from the intimate space of the home to the masses, or public body, in the “civilizing” discourses of philanthropic “giving” through the arts and culture.

Even considering the context of these social proprieties, and though Children did act as teacher, Atkins’ relationship with her father seems to fall outside of a top-down model of learning from (male) expert to (female) student. Accounts of their relationship, as few and far between as they may be, point to a mutual admiration in recognition of their shared enthusiasms.

When Atkins’ father passed away in 1852, it appears that making cyanotypes provided some source of comfort and distraction in her state of deep grief. Collaborating with her half-cousin, Anne Austen Dixon, whom she considered as good as a sister, she went on to produce Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns in 1853, and Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Flowering Plants and Ferns in 1854. In addition to writing fiction, self-publishing two crime novels — The Perils of Fashion in 1852 and A Page from the Peerage in 1863 — Atkins also (pseudo-anonymously) wrote her father’s biography after his death.

In a book consisting almost entirely of images, it’s Atkins’ few pages of written words that reach into the gaps of her subject, in resonance with a digital age of infinitely revisable horizons. Shadows of doubt come to the surface in Atkins’ own awareness of what is missing, or what might be lost, in the notes she makes in British Algae, which provide glimpses of her own intents and hopes for the work.

In Blue Mythologies: Reflections on a Color, Carol Mavor looks at taxonomies of animate and inanimate objects and subjects, human and non-human bodies, in the blue photocopies that make up Oval Court by the British artist Helen Chadwick and Anna Atkins’ cyanotypes, describing them as a nuanced species of writing.

“Chadwick’s and Atkins’ blueprints are photographic equivalents of Roland Barthes’ ‘To Write: An Intransitive Verb?’ (the 1966 lecture and essay),” states Mavor, proposing that “their work seems to bespeak an essay that Barthes never wrote, but might have, entitled: ‘To Photograph: An Intransitive Verb?’ Or even, ‘To Blue: An Intransitive Verb?’”

Barthes had been planning to write, Mavor tells us, ideas germinating towards novel form. However, in 1980 — the same academic year in which he had been teaching a course entitled “The Preparation of the Novel” — he was killed in a road accident. His novel left unwritten, Mavor makes of this an “undelivered, intransitive, gesture of to write.”

In lieu of archival bodies of evidence or bodies present enough to write their own experience, this turn towards the gestural pulls us closer to Atkins’ voice. We are taught not to make up stories, but in some circumstances, and our conversations with history, might it be the generous thing to do? We can almost visualize Atkins’ enthusiasm when in sending cyanotypes by mail she included instructions for recipients to learn and recreate the process for themselves. Her keenness can be heard in the tender recognition of others’ contributions to her own work and to her life, and of needing to share such discoveries at the margins of the scientific and academic worlds that she was very much exposed to, but within which she could not fully or officially participate.

* * *

“Every man his own printer and publisher,” William Fox Talbot wrote excitedly of photography’s promise to deliver a technology destined to succeed the printing press. Anna Atkins’ cyanotypes brim with the same radical sense of possibility.

Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions predated Talbot’s Pencil of Nature by a year, in case we forget that Atkins’ “amateur attempts” were a moment of experimental cross-disciplinarity, published at the cutting edge of science and technology, preempting modern artistic approaches and methodologies. Though borne of scientific intent, her prints were an act of creative self-publishing, inadvertently bridging public and domestic worlds. As labors of love they were gifted as tokens of affection outside of patriarchal or professional expectation. In many ways, her “species of writing” shares ancestry with a spectrum of genres which necessitate personalized and creative modes of witnessing and remembering, from psychogeographical accounts of locality to popular nature writing.

Aside from the roundly historical importance of the work, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions was produced in a period marked by an appetite for progress and speed, but also from a culture of containment and fixity. And yet it is almost impossible to apply the same description to Atkins’ work — nor would we want to. Bourgeois, progressive, feminist, feminine, beautiful, decorative; these distinctions might prick at modern critical sensibilities but they also speak to our own present day burdens of definition in language and meaning.

Atkins fulfilled the brief she set out to achieve, but in doing so created an outcome with a mysterious and lasting legacy, far in excess of scientific or botanical interests. Now that a preservation aiming to fix species, habitats, landscapes, buildings or artifacts into states of indefinite or immutable permanence has been broadly supplanted by resourceful strategies of care and custodianship, how does this sea change influence contemporary evaluations of Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions?

I like to think that, in the way of many artists, and in commitment to her subject and a sensitivity to the specifics, Anna Atkins understood how vital it was to pay attention to the smaller, less-observed details, for these might one day contribute towards a picture bigger than her own.

1. The Calendar of the Correspondence of Sir John Herschel is an index of 14815 entries of correspondence sent to or from Herschel and includes letters that show his concern at how social conventions of the time effectively excluded talented and intelligent women from formal education or recognition. Herschel was also a friend and mentor to women such as Julia Margaret Cameron, one of the first female photographers of the 1860s, and more famously, the polymath Mary Somerville. His letters to these women reflect the encouraging influence from which, given the close social connections between the Herschel and Atkins’ families, Anna Atkins surely would have also benefited.

2. Both men were instrumental in the landmark development of achieving a truly fixed photographic image, though it was Herschel who discovered several key chemical advancements in the area and Talbot who understood the urgency of commercializing the technology for a mass market.

3. Blots and blanks, in turn, remind us of other negative spaces of invisible or undocumented labor. Anna Atkins’ social milieu and means — her affluent family background and social circles, inherited land and wealth, and her marriage to a merchant banker with holdings in Jamaica — would have meant that in making her cyanotypes she was likely to have been greatly helped by domestic staff, invariably working class men or women and girls in service. While their complete absence from the story might be unsurprising (like the dwindling archives of Atkins’ personal papers and letters, more the symptomatic partiality of histories than lack of evidence or of their existence at all), as an upper-middle class woman, leisure time was available to Atkins in ways unknowable to the women who most probably worked for her. If servants were instructed to be seen and not heard, to only speak once spoken to, so the invisible women who likely facilitated Atkins’ work speak volumes about the spectrum of privilege that enabled her prolific efforts.

Anna Ricciardi is an artist and writer, living and working in London and Kent. Her critical and creative writing has appeared in journals, publications and exhibition catalogues. http://annaricciardi.com.

The exhibition catalogue for Bloom, published by Horniman Museum & Gardens, explores the crossovers between fine art, early photography and natural history with essays by Ricciardi, Edward Chell and Hugh Warwick. Fully colour illustrated featuring cyanotypes by Anna Atkins and paintings by Edward Chell. Available from www.edwardchell.com/

This post may contain affiliate links.