Tr. by Diane Oatley

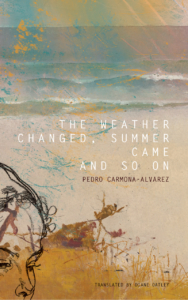

Pedro Carmona-Alvarez’s third novel, The Weather Changed, Summer Came and So On (translated from Norwegian by Diane Oatley), is to books what a crab apple is to fruit: pretty to look at, nauseating to try.

The pleasingly-designed book, which won Norwegian National Radio’s award for best novel, is about a married couple, Kari and Johnny, and their daughter, Marita, and how all three of them survive the aftermath of a freak accident: the couple’s first two daughters are killed by a drunk stranger who accidentally crashes his car into their house. A weighty premise, for sure, and the novel collapses bathetically under it. I finished The Weather Changed feeling as though I’d waded unprotected through a moist breeding ground of quasi-profound clichés.

The Weather Changed is set in the 1950s and 60s. The story takes place equally in Oslo and New York City. Kari is Norwegian, and Johnny is American, and therein lies much of the novel’s artificial, ‘relatable’ tension (more on this later). The book comprises three parts and Carmona-Alvarez tells it through two different narrators: an ostensibly innocent-wise (a la William Blake’s Songs of Experience), though really patronizing, third-person narrator who awards more sympathy and space to Johnny than Kari, and who seems to assume that he knows the Deep Truths about life before having lived it (I picture him wearing a tweed hat); and sometimes through the stylish first-person point-of-view of Marita, a quirky teen who likes to take black and white pictures and reminisce about the good old days she spent in sunny California with Dad:

I remember California. I remember the afternoon light, all misty and strange. Dad would take me for drives . . . We drove through the streets, ate hamburgers in the car. I saw a whole lot of night-kids, under-the-bridge-kids. And girls like me. Skinny girls in Converse sneakers. Girls who trembled, pulled down their jeans and thought about their souls all afternoon long.

Overall the prose style is quintessentially Scandinavian — or no, that’s not right. The prose style is more so what a Scandinavian writer might assume an American reader considers quintessentially Scandinavian: clean, simple, efficient, sort of minimalist, like something from Ikea.

I’ll summarize the novel so that it has something of a fair chance to speak for itself: it’s 1956. Kari and her family emigrate from Norway to New York City. Kari, who is “beautiful,” meets Johnny (“Beautiful accent, Johnny says. Where are you from?”), and they fall in love and marry. Johnny’s father, a wealthy textile factory owner, offers his son a prosperous job at the factory. Kari births Vera (“Johnny cries and then he takes Vera in his arms”). Then she births Ann. Both Vera and Ann are “beautiful.” The Cold War looms but Johnny and Kari are happy. That is, until the “bad luck begins.” First, Johnny’s cousin, Howard, otherwise irrelevant to the narrative, hangs himself after embezzling family money, and Johnny learns to his surprise that he’s broke. Second, there’s the “accident.” One night, after Kari and Johnny have put Vera and Ann to bed and gone out, a drunk man, also otherwise irrelevant to the narrative, crashes his car into Johnny and Kari’s house and crushes the sleeping girls. Days later, in her insomniac grief, Kari opts unwisely to see her daughters’ deformed bodies at the morgue, and right away she understands, “unmistakably — that life would never be good again.” And Johnny?

For the first time since his childhood, he talks to God.

Why? he asks. Why us, exactly? he asks. What’s the point?

Who are you, really?

Slip ahead to 1967. Kari and Johnny move to Oslo. Both are tortured by grief, but only Johnny manages to not get depressed or take painkillers (at one point he compares his own personal struggle to the war in Vietnam: “His war. A war other than the big one, but a war nonetheless.”) Alone, he attends a Fourth of July celebration in Oslo, where he meets a beatnik American musician who introduces him to Bruce Springsteen’s music. Kari births another daughter, Marita. Johnny wants to tell Marita about Ann and Vera but Kari forbids it. They start to fight. They fight for years. Johnny flips through old photo albums. Kari wears “more make up” and goes out late to bars and starts having sex with “a man from Bergen.” Johnny is jealous, but he remains faithful, though homesick. He grows obsessed with Springsteen. He tells Marita about Ann and Vera. Kari finds out and they fight some more and their love grows “twisted. Like an old glove.” I won’t spoil the rest.

So the novel, whose original Norwegian title, by the way, is Og vaeret skiftet og det ble sommer og så videre, which literally means, “And the weather changed and it was summer and so on” (a refrain that repeats throughout the novel), has its faults, of course. To name six: it’s yet another novel where a husband deals with tragedy more rationally and selflessly than his depressed, painkiller-swallowing — and all but ‘hysterical’ — wife. Yet another novel where an ostensibly wise and distant third-person narrator awards more space and sympathy to the main male character than the female. Yet another novel where a woman’s downfall involves wearing “more make up” and going out late and drinking and having sex. Where main female characters are again and again valorized for their physical “beauty.” Where the major turning point (the freak accident) is an incident of deus ex machina. Where the male author tries unconvincingly to write from the point of view of a quirky (she wears Converse sneakers) teenage girl.

And if that weren’t enough, the novel’s take on cultural differences is embarrassingly stereotypical, here and there intended, it seems, to make both Norwegian and American readers feel fuzzy-wuzzily-proud of their national identities, which here really means their respective brands of whiteness. America, according to the novel’s narrator, is “something enormous and open and free. Something created for the future to inhabit.” A fun land to invent new identities, forget the past, eat burgers, make noise, and dance to Bruce Springsteen. Norway, by contrast, is a cold and quiet land where pain is swallowed like painkillers — how ironic — and history haunts and there’s lots of snow and it’s really annoying but you’re supposed to remove your shoes at the door — something Johnny explicitly refuses to do, how symbolic. This passage about Johnny, set in New Jersey, speaks for itself:

It hits him. The heat and the noise, so unlike Norway, all the tattered teenagers hanging out on the street corners as [Johnny’s friend] Billy drives in towards Fairview. Pizza shops a Norwegian would never in the world have dared to enter. People like that can cut you up with a look . . . When Johnny talks about Norway, Billy doesn’t really listen. He can’t grasp the silence Johnny starts talking about; the afternoons with the state television channel on, the frozen grins on everyone he met, the cold Oslo winters and the snow that blanketed the cars and muted all the sounds, as if the entire city was a fucking sound-proof interrogation room, a damn presence. (232)

To be fair, Carmona-Alvarez is here employing free indirect discourse (see, “fucking sound-proof”), so it would be naïve to conflate Johnny’s anthropological observations with the narrator’s. But still. That doesn’t excuse Carmona-Alvarez for ever writing a character that makes such unbelievably unobservant observations in the first place. I’ve lived in Oslo, and I’ve met Norwegians, and I think it’s pretty reasonable to assume that after over a decade of living in Oslo any competent observer, Johnny included, would know that Norwegians don’t fear pizza shops.

And if that weren’t enough, Carmona-Alvarez uses superficial cultural differences to dramatize personal differences and render conflict. Take, for example, the following fight between Kari and Johnny:

Kari says he can go to hell. She says it dryly and calmly.

You don’t mean that, Johnny says.

You don’t know shit about what I mean and don’t mean.

She says it in Norwegian.

Disregarding the fact that by this point in the novel Johnny has lived in Oslo for roughly a decade and speaks at least basic Norwegian (it’s actually an easy language for Anglophones to learn), this is how Part II of the three-part novel concludes. Not with a bang, but with a whimper, which is meant to be a bang, på norsk.

Pretentious is an overused word, but that’s what The Weather Changed is, pretentious. So much so, in fact, that it’s not too far fetched to speculate as to whether its author, a poet-cum-novelist who, by the way, has won the Cappelen Prize, the Hunger Prize, and the Norwegian Poetry Society’s Prize, could write something much better, and far more artistically dignified, but chose instead to construct precisely the kind of novel that wins prizes — a novel that, to twist a memorable Eve Sedgwick phrase, “kinda hegemonic, kinda subversive,” is ostensibly subversive, but ultimately hegemonic (which is one of the worst things a novel can be) — in order to both make fun of the literary-industrial-prize-awarding complex and reap its benefits.

Speculation aside, though, the book is still a sustained example of bathos. Harsh, yes. But how else to respond to a book that’s written in prose that’s meant to sound experienced and wise but actually sounds jejune and patronizing? To a book about history that says nothing new about the past or the present? To a book that’s all at once heteronormative and nationalistic and subtly misogynistic and replete with clichés of all types? The Weather Changed is a book better left unread, or, if read, unremembered.

Gavin Tomson‘s writing has appeared in Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly Journal, National Post, Joyland, and Salon. He lives in Toronto. You can follow him @GavinTomson.

This post may contain affiliate links.