What is it to know? How much should we know? Should we know? I’m reminded of a quote by the Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard. Upon receipt of a major Austrian literary award, Bernhard thanked the audience this way: “When one thinks of death, everything is ridiculous.” There is another way to read this besides the obvious snub to the supposed authority of cultural institutions: What is it to be alive, if everything dies and turns to mulch? The exhilaration of embracing and inhabiting that anxiety of imminent death — of ignoring the pressures to “be happy” and to achieve in mainstream society — may be the real experience of being alive. That is, the shock of escaping imposed narratives and sanctioned forms of living is the shudder of the real. So, what is it to know?

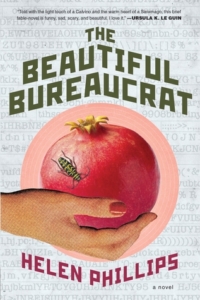

Such is the central concern of Helen Phillips’s debut novel, The Beautiful Bureaucrat. Fresh “hinterland” transplants and newlyweds Josephine Anne Newbury and Joseph David Jones struggle to find their bearings not only in the intimidating unnamed city, but also as persons unto themselves. We follow Josephine as she struggles with her infant marriage and at her not-quite professional job at a massive data entry operation known only to us and her as AZ/ZA. Inside the windowless building, the promise of new beginnings that she finds is devoid of the fullness she envisioned. Anxiety and doubt over the future leads to more anxiety and doubt — and “The Person with Bad Breath.”

The person who interviewed her had no face. . . . The interviewer’s skin bore the same grayish tint as the wall behind, the eyes were obscured by a pair of highly reflective glasses, the fluorescence flattened the features assembled above the genderless gray suit . . . . The lips, dry and faintly wry, parted to release the worst breath Josephine had ever smelled.

Institution and person are exchangeable terms here; life and self literally disappear into office-gray carpet and concrete. You might be tempted to utter beneath your breath, like a sacred passcode, the name Kafka, but I caution you against it. The Beautiful Bureaucrat revels in its playful and dark take on contemporary life, where everything — reality, love, relationships, the mundane — is out of proportion, and yet never loses sight of its commitment to the brazen, and perhaps stupid, curiosity of the human. Josephine and Joseph flee the hinterland, and their families, in “hope of hope.” Kafka’s hope is almost always a ruse; if there are any aesthetic legacies to be traced here, they’re closer to the fantastical elements found in Gilliam’s Brazil, or the fabulism of Calvino, both employed in The Beautiful Bureaucrat to dazzling effects.

The Beautiful Bureaucrat is obsessed with how much data, and its seemingly authoritative claims to reality, the brain can take before it begins to self-destruct. Josephine’s only task at AZ/ZA is to maintain one part of the massive Database, whose function she unpacks over the course of the novel. As Josephine gazes down narrowing halls, the walls possibly closing in around her, the mysterious threat of the Database bores deeper into Josephine. Despite her best efforts, she becomes punctuated by the Database’s grammar with scary bureaucratic efficiency. Her eyes dry out, perpetually bloodshot from the steady violence of her computer screen, and her fingers turn gray from paper and ink. Josephine struggles against this transformation, haunted and hunted by the “scratches, smears, shadowy fingerprints, the echoes of hands” that decorate her drab office walls.

Outside, she depends on Joseph to buffer these turns-for-the-worse with his uncanny talent for shrugging off the slime of bureaucratic life. She routinely arrives home to one of their several squalid sublets to find him cooking something that can barely be called dinner, but something that steels her against bureaucracy nonetheless. But soon, the Database begins to “[float] in her brain like a net for catching and killing,” and she depends on Joseph more and more to buoy her from the never-ending flushing toilet of “HS” numbers. When they make love, it isn’t Joseph’s name she screams, but “041-74-3400!” — Joseph’s Social Security number. And when Joseph suddenly turns erratic and cold, refusing to account for his disappearances, the marriage turns cold. The Database forces its way in; she begins to graft the coincidences and wordplays once shared with Joseph onto the Database. “BOOMHAVEN. Boom, haven! Her haven-tomb; another deathly coincidence, just like the ones she had been so keen to find in the Database.” Data replaces Joseph.

So what is the Database? When a precious Friday is stalled when the Person With Bad Breath barges in with “’fifty-six for immediate processing,” Josephine resigns herself to “let the letters be nothing more than letters, the numbers nothing more than numbers.” But come next Monday, she happens upon a coincidence that goes beyond the clever pun.

NEWLYWEDS, CHEF, ENGINEER AMONG PLANE CRASH VICTIMS . . .

Sam Fishbein.

Sam Fishbein.

FISHBEIN/SAMUEL/BLAKE

At this time, an estimated fifty-six fatalities.

Does she manage the death dates, or are they the dates of when one will die? Driven by a need to know what her work means, Josephine transforms from Sisyphus into bureaucratic detective. After she’s broken into the restricted-access File Storage, what she finds in the dark corners of AZ/ZA unties the fragile knot of Josephine’s self.

Framing Josephine’s disintegration are a sooth-saying diner waitress, an over eager office “frenemy” on the brink of utter collapse, and a bureaucracy that may play God with numbers. These are all ciphers for the answers we seek to solve in the terror of being alive. But answers and closure, Phillips shows us, are not innate to human consciousness, but programmed in the brain. When Josephine is between forms — the easy closure of an “HS Number” and the ever-present imminent nothingness of death — she reveals us to the naturalized con of language. To name and to know is always already a fiction. Josephine’s catch-22 of knowing and trying to un-know isn’t only a metaphor for coming into her own mortality, but is also a metaphor for the ways in which we can know, which one is truth and fiction, or simultaneously both.

It’s also a metaphor for Phillips’s dazzling handle of narrative form, how it weaves the urgency of a thriller into an otherwise tried-and-tired marriage plot in the key of literary modernism. Phillips’s vital prose struggles against its animations of the terrifying drabness of AZ/ZA, a tension that elevates The Beautiful Bureaucrat into a form unto itself. We get the sense that the language itself is hungry to know what it is discovering, while also afraid of what it will find, just like our heroine. At times, The Beautiful Bureaucrat behaves more like a fable dressed up in the length of the short novel, or a long novella, further hidden behind the veneer of the psychological novel, but rooted in an allegory that questions its own veracity. This is The Beautiful Bureaucrat‘s ultimate strength: a work that is honest about the fear and risk of being alive in a world increasingly dominated by algebraic functions and Excel spreadsheets that go beyond data. But The Beautiful Bureaucrat doesn’t succumb to an easy cynical apathy or patronizing, avuncular consolation. To be alive in one’s body brings with it the anxiety of knowing one will die, but the beauty and terror of life is in not knowing when. To be caught between states, between forms, and between languages opens up our selves to the world, and all the risks that come with it, and what a terrifying, but exhilarating, world it is.

This post may contain affiliate links.