[Gallic; 2015]

[Gallic; 2015]

Tr. by Julian Evans

During the waning days of World War II, a young soldier holds captive a general of the German army on the island of Crete. As the sun rises over Mount Ida, the two men find themselves finishing one another’s quotations of Horace. Like stories of French and German forces in the First World War spending Christmas together on the front — and going back to shoot at each other the very next day — these unguarded moments speak to our common bonds, and the mutual tendency to forget all too soon how very much we are related.

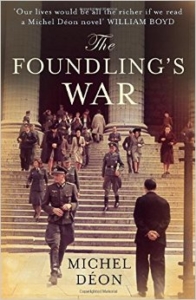

The very nature of wartime relations and associations — beneficial and misaligned — form the core of The Foundling, an inestimably entertaining two-volume series by Michel Déon comprised of The Foundling Boy and The Foundling’s War. Now 95, living in Ireland with his wife and many horses, Déon is one of France’s most celebrated writers. The Foundling series, first published in France in the 1970s, is now making an underreported entrance into the forum of American letters.

Déon’s novels take their name, and much of their ribald plot, from Henry Fielding’s 1749 novel, The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling. No less an authority than Samuel Taylor Coleridge declared Fielding’s novel one of the three most perfect plots in all of literature. But it was due to the French translation by Pierre-Antoine de La Place that Fielding owes his popularity. La Place, who also first translated Shakespeare into French, held little regard for textual fidelity and did much to improve Fielding’s language for the French reader.

A menagerie of correspondences and accordances abound in Fielding’s novel and Déon’s work reflects an abiding study of Fielding’s style. Not unlike the recent novels of Elena Ferrante, Déon’s characters — taking their cue from Fielding’s mastery — assume integral recurring roles in the narrative, a risk ensuring the reader a serial interest in the story’s development.

Julian Evans’s translation of Déon’s frequently funny picaresque tale is a charming, adventurous read, a “must read”, really, because of Déon’s rational take on all our squabbling. The Foundling is the history of Jean Arnaud as he squirrels away some elbow room for himself in a world mired by the aftershocks of war. Jean is born in 1919, the year of the Treaty of Versailles. Jean’s adopted father, a poor gardener, is un mutiles de guerre, one of the 1 million Frenchmen left badly maimed by the First World War. The myriad mutilated, undead veterans were daily reminders of a conflict many Frenchmen wished to forget. Jean’s family is no different. As an infant, his father sings to him, as if a lullaby, “And all you poor girls/ who love your young men/ if they reward you with children/ break their arms, break their legs/ so they can never be infantrymen/ so they can never be infantrymen.” Despite the warnings of his father, and the promises Jean makes, he will one day serve his floundering nation.

But in the French pastoral countryside in the intervals between wars, Jean grows up hale and strong, with just the right amount of sexual impropriety (and fumbling) to convince us of his believability. He is a precocious child who will grow into a man’s body but will never seem to lose his boyishness. Girls will fall into his arms like manna upon the poor and needy. For the impatient reader wondering when the author will narrate Jean’s development from infant to infantryman, Déon interrupts the narrative:

I sense that the reader is eager, as I am, to reach the point where Jean Arnaud becomes a man. But patience! None of us turns into an adult overnight, and nothing would be properly clear (or properly fictional) if I failed to illustrate the stages of our hero’s childhood in some carefully chosen anecdotes. This is, after all, the period when Jean is to learn what life is, or, more specifically, when he is to experience a range of feelings, aversions and passions which will imprint themselves readily on him and to which he will only discover the key very much later, around the age of thirty, when he begins to see things more clearly.

Life to Jean seems very much like a Alexandre Dumas novel, or, more contemporaneously, a Patrick Leigh Fermor travelogue. But as Jean travels — to England, to Paris, to Portugal — France is rotting from within.

Between 1918 and 1940, the years, roughly, during which Jean comes into himself, France had no fewer than thirty-four governments. Meanwhile, dictators in Italy and Germany and the Soviet Union thrived. Frenchmen were much too busy proclaiming their pacifism to notice the uniformed barbarians knocking at the gate.

“You can be a virgin in horror the same as in sex,” Céline writes in Journey to the End of the Night, a novel Jean much admires. But war provides Jean and his comrades a glut of opportunities for fleeting love and rollicking adventure. Recalling his own experiences in World War II, Déon writes: “I was among those French who otherwise would never have met peasants, workers or waiters. That helped a lot in my life of writing.”

Jean spends the vast majority of the war in Nazi occupied Paris. But, of course, the city is a playground for German officers. Though there’s significant hardship present, Déon’s Paris looks less like Guernica and much more like a scene straight from a gay Lautrec poster. The show must go on, as an old saying goes, but in this case it was Nazi-ordained that Paris keep up appearances. In a 1940 letter Goebells writes, “The result of our victorious fight should be to break French domination of cultural propaganda, in Europe and the world. Having taken control of Paris, the center of French cultural propaganda, it should be possible to strike a decisive blow against this propaganda.” But the Nazi soldiers were to temporarily enjoy the show, when they weren’t goose-stepping down the Champs-Elysées.

Jean thrives in this new environment of intrigue, befriending resistants and collaborateurs alike. Though possessing a strong sense of right and wrong, Jean’s allegiance is to himself and his comrades, some of whom, like the dashing con-man Constantine Palfy, are unforgettable.

“Who still believes in the French? But who does things better than they do?” Palfy asks Jean during the interwar period. But our world isn’t quite so different from Jean’s time, a time of intrigue and deception. When Europe seems ever to be on the mend and global superpowers threaten one another with their mincing steps, Déon sheds riotous humor and immense delight on the misgivings of men.

Andrew Mitchell Davenport is a middle school teacher, and a writer, in Brooklyn. You can find him on Twitter here.

This post may contain affiliate links.