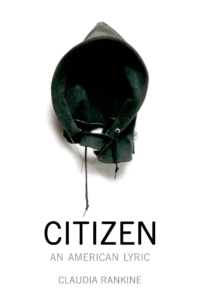

Citizen is a slim volume, heavier than it looks. On the cover is a reproduction of an assemblage by artist David Hammons: a dark worn sweatshirt’s dismembered hood propped up by wire and mounted, as if it were a taxidermic hunting trophy, onto a white wall. For the contemporary reader based in the United States of America, the image immediately calls to mind the iconic hooded sweatshirt worn by a now eternally seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin on the night of his murder. Hammons, who made this piece almost twenty years ago, couldn’t have anticipated the murder of Trayvon Martin and the events that unfolded in its aftermath — nor did he need to. The signifying power of the black hoodie, it seems, has aged well since 1993, and its longevity only attests to the persistence of many of the dominant strains of racist ideology in the contemporary United States. Indexed within the pages of Rankine’s “American lyric” are events occurring in a gradient of publics which provide the foreground and background for an America in which a(nother) young unarmed black man is violently policed out of existence. We are drawn deeper into a murky, melancholy world punctuated by the syncopated rhythms of racism and simultaneously, through the sinuous narrative structure and ambiguous collection of supportive images, kept at a palpable distance.

Claudia Rankine is an important voice asserting the fallacy of a postracial multicultural America, in which citizens of all physiognomies and histories are supposedly guaranteed equal access to resources, opportunities, and fair treatment in the eyes of the law. Like many other cultural workers across genres and media who seek to expose the highly racial arrangements of contemporary America, she lays out counter-narratives that illuminate the realities of life on the receiving end of anti-black racism. The events described within these pages range from an unnamed character’s uncomfortable encounter in line at a drug store to a detailed account of Serena Williams’ struggle to find acceptance and support on the tennis court in the face of biased umpires, mocking commentators and peers. The ten “scripts for situation videos” made in collaboration with artist John Lucas that comprise the sixth section (and whose corresponding videos can be found on Rankine’s website) recall widely publicized world-shifting events such as the Jena Six case and the murder of Mark Duggan in London. The quotidian and the exceptional accumulate to form a devastatingly immense, expansive, and immediate testament to anti-black racism in America. The power of these narratives is indeed partly in their mass and volume as a whole, but it’s also in the way their telling maps the territory of what happens around the situations described, how they are incorporated into the body, the traces they leave.

The author employs not the authoritative I, nor the collective we, nor the detached he, she, or they, but rather an instructional, directional you to relay these narratives. This device works both to bring us closer to the experiences described, and to help us recognize the space between our own lives and those whose moments fill the book’s pages, to observe that distance’s contours and textures. We don’t know precisely whose department head complained about having to hire a person of color when “there are so many good writers out there,” whose would-be therapist exploded in fear and threatening suspicion at their first in-person meeting at her home office, who it was that couldn’t keep quiet after a fellow Starbucks customer in line referred to a group of young black teenagers at a nearby table as n—–s. Rankine’s you dis-engages the subject, dislodges the situations from their particular contexts of belonging (in one set of lived experiences, one time and place, one specific network of bodies) and projects them into a broader, looser constellation.

Interspersed with these personal narratives of everyday racism is a pastiche of cultural references. Images, texts, and events are drawn from a wide variety of sources, and given Rankine’s scrutinizing treatment. Serena Williams shares the same couple of pages with YouTube sensation Jayson Musson (Hennessy Youngman of Art Thoughtz fame) and Zora Neale Hurston. Taken together, they teach us about black anger, its roots and manifestations in different spheres. Narratives taken from the author’s personal experience as well as those of her friends are offset by reproductions of work by well-known artists such as Glenn Ligon and Carrie May Weems as well as documentary images culled from popular sources. Rankine is omnivorous, just as likely to buttress an idea or evoke an affective response with Butlerian theory as an image of one of Nick Cave’s sound suits or a set of television stills from an infamous World Cup match. It seems as if there is no comprehensive logic to the selection and placement of most of these images, and the result is at once exciting and disorienting. In a conversation with Lauren Berlant, Rankine herself states, “I was attracted to images engaged in conversation with an incoherence, to use your word, in the world. They were placed in the text where I thought silence was needed, but I wasn’t interested in making the silence feel empty or effortless the way a blank page would.” The images provide a pacing for the reading experience, something for the eyes to rest on while the language settles into the mind. Through this assembly of text and image, alternative pathways are opened up for thinking (and feeling) through individual and collective experiences of racism. The current conversation on race in America is highly predicated on the languages and conventions of reportage and (to a lesser extent) those of political criticism and literature. Citizen suggests another way in.

At the core of Rankine’s investigation into race in America are the performative capacities of language: to do harm on the one hand and to enact resistance on the other. This is familiar territory for those who engage in discussions of social justice and identity politics. We live in an age of trigger warnings and call outs and contentious debates around those practices. In Citizen, as we look more closely upon this terrain of words that hurt, words that have the power to call up traumatic histories and deploy them into the present, Rankine urges us to widen our gaze. The imperative is not just to point to specific languages and specific people that they emanate from, but also to examine the array of responses, both social and internal, that can and may emerge from the addressee. For all of the incredulous acknowledgements of racist speech (“What did you say?” becomes the book’s refrain) and measured requests for reconsideration, there are just as many painful silences and avoidant subject changes, words that get choked on and swallowed back down. Rankine tracks these responses from their origins to their sites of impact on the body with curiosity and empathy, never judgment or scorn.

That the experiences that are narrativized in Citizen are inflected with racism is self-evident; Citizen is focused not on cataloguing and calling out but instead on attending to that which is set in motion on an affective register when an interchange or event occurs. The question of how these states of being transform in time and work to organize and/or disorganize the self becomes a central concern of the work. We are presented with a sort of affective alchemy in which emotional responses that arise from the racially subjugated — anger, fear, sadness — are imagined as substances with unique and mysterious interactive properties and powerful potential effects. Public health researchers and medical practitioners have shown that repeated exposure to racism can interrupt and alter vital psychological and physiological processes, and have even come up with special terms — John Henryism, the weathering hypothesis — for this phenomenon. Citizen takes us further, articulating how the implications of racialized stressors extend to the formation of individual subjectivity, one’s embodied experience of the world. Rankine writes:

Yes, and the body has memory. The physical carriage hauls more than its weight. The body is the threshold across which each objectionable call passes into consciousness — all the unintimidated, unblinking, and unflappable resilience does not erase the moments lived through, even as we are eternally stupid or everlastingly optimistic, so ready to be inside, among, a part of the games.

Repeatedly we are shown how Citizen‘s characters are unable to mobilize their apparent class privilege or professional qualifications for protection in the face of such hazards. Even with our integrated schools, our black president and our employment non-discrimination clauses, destructive forms of interpersonal and institutional anti-black racism bleed into the present and remain tangled up in how we interact with one another, how we experience public space and private life. Citizen is no instruction manual on how to deal with racist aggression on any scale. It is an account of the complicated nature of navigating the self and the social under the tyranny of oppression.

Hannah Klein is an artist and educator based in Oakland, California. Her website can be found here.

This post may contain affiliate links.