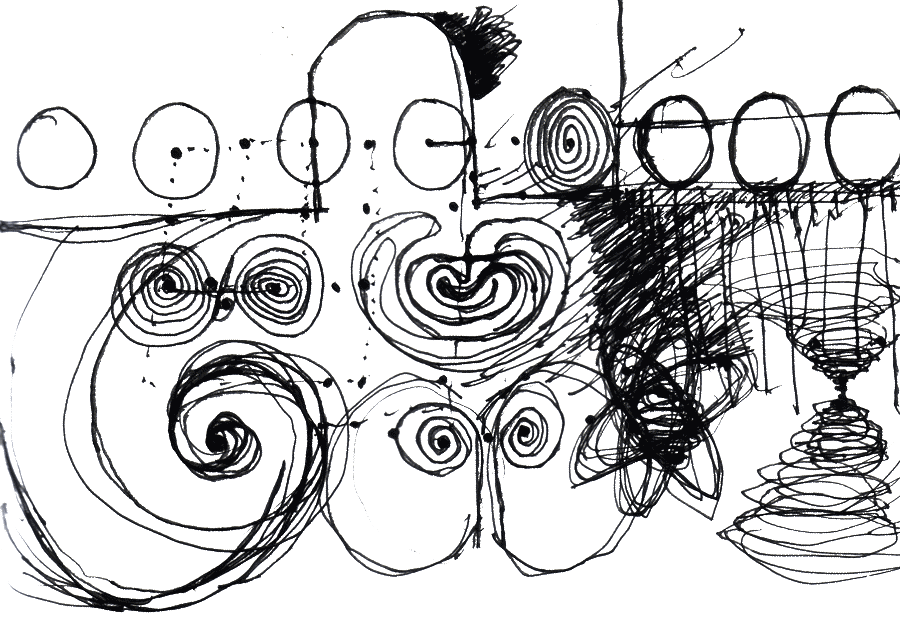

Louise Bourgeois says a spiral is perfectly predictable and a knot is perfectly unpredictable.

Once I had to choose “an object.” The object was to be the only thing I would bring to a twenty-four hour live-streamed performance experiment. During this time, myself and the other participants had agreed not to speak. I was choosing a substitute for my voice. I could not choose a pencil because a second object is required to sharpen it and without the necessary suitable surface it would retain only symbolic value. I did not choose, as a deliberately obtuse part of me suggested I should, a smartphone — the object to trump all objects. I considered white paint or a musical instrument. My sister, when I asked her to choose one thing from the list of my considerations, didn’t even skip a beat. “Take the string,” she said immediately.

It was the string that I ended up taking; or rather several reels of string tied together and rewound into one large ball the size of a grapefruit — a single object; maybe 200 meters long weighing less than 500g. I’ve known my sister long enough to know when she is dead right. There is something intoxicating about devoting so great a quantity of such functional stuff to glorious possibility. I bought it from a discount shop, the kind that sells aluminum foil trays and computer cables and extension cords and alarm clocks. The string had been made in China — from a bleached, starchy cotton — and wound and shrink-wrapped in clear plastic, thermoset I guess, since it retained the shape of the reel after I tore it away. Not yet an actual ball of string — I write “reel” but the string was not wound onto anything, though it must have been once, in the factory. It was a struggle, then and now, to find vocabulary with which to describe it. What is the name for the hole at the centre of starched stiff and machine wound string? There must be a technical term for something so particular, I just don’t know it. It is difficult even to Google it correctly. The search brings up the string theory of physics and quantum mechanics, string from computer code and string bikinis. Perhaps you want rope, or yarn or instructions for tying a knot? String is, or was until quite recently, something so ubiquitous we do not often speak or write precisely of it.

Hestia Peppe contributes a monthly column for Full Stop of still life writing concerning sugar givers, salt cellars, talismans, fetishes, and transitional objects; an experiment with vanitas not so much as momento mori but as animist memoir.

Exactly what the string cost I do not recall, except that it fell into that category of objects, which, not being made of petrochemicals, are still sold for more than ninety-nine pence and seem as a result somehow luxurious when really it is just that they actually work. I specifically wanted the cotton kind, because this is the string I imagine when I think of string (it carries the correct degree of cliché) and because from experience I knew that the plant fibres would be far more comfortable in my hands all along the silent hours than more readily available nylon.

I had to look in several shops before I found the type of string I was looking for. These days objects are rarely tied together for anything other than decorative reasons. Gardening string is less obsolete, but the wrong colour. Not everywhere that sells sellotape carries string. In the first piece of performance art I ever saw live, the French artist Skall used sellotape to bind himself to furniture in the lecture hall, wrapping it around himself and a table, institutional plastic and metal chairs. He dragged the furniture after him and into the walls, a terrifying spider snared in his own web. Sellotape destroys itself on contact with the world; it is sacrificial. I wanted something I could work with for twenty-four hours.

These reels of string unwind most easily from their open centre (still without a word for it). Out of a void comes a beginning. I didn’t want the indeterminate squared end ovoid shape of the reel, a shape made by a robot arm with specific practical concerns that I do not share. I want a sphere. I want to watch the accretions of layers pass through my hands. I will touch every part of it. The end is pulled and the void grows, the object is eaten out from the inside to become an Other, the reel disappears and a ball grows out from the centre in my hands. This takes about ten minutes, depending on how fast I wind. When I come to undo it I will pull the other end away from the edge of itself and begin again.

Even before the performance begins I will have wound, unwound and rewound many times, following the string as it does and undoes itself. There are no choices in the path. I imagined myself at the centre of a glorious tangle, like Skall. But now that the string is in my hands I’m obsessed with the string as line, as spiraled potentiality, and it’s transformation into the ball, a treasure I want to hold to my body. Like Ariadne, I needed a map I could touch and take into the dark with me. The spiral is both the labyrinth, and the way out of the labyrinth.

This post may contain affiliate links.