A woman’s work is never done.

I am the business manager, communications director, public face, compassionate heart, occasional mother figure and overall super-powered desk girl of the study abroad art program where I currently work. I know all things. I manage all things. This is not an exaggeration. Were I to mutiny and leave — say, hitch a ride into Toulouse to make landscape paintings — the program would fall apart. No question about it.

In addition to being the keystone of the program, the biz, the head and the hands, etc, corporate lingo, whatever: I am also being paid 5% less than my male colleagues. I found out because — surprise! I’m the one with the clerical duties who handles payroll. Is it 1950 or what?

Of course, I shouldn’t have to tell you there’s a systemic pay discrepancy in America — women earn, on average, about 80 cents to a man’s dollar. The wage gap grows even more pronounced when you sort the data by race: white women earn 78 cents to the white man’s dollar, while black women and Hispanic women (as cited) earn 69 and 60 cents, respectively. For the record: all of my immediate colleagues are white men, who will always earn a dollar for a dollar, bless their white male hearts.

If anything, I was simply surprised that the inequality was so… obvious. Forget neoliberalism; this was old-school tactics. It was as though the administration hadn’t even bothered to hide it from me.

But it’s very simple, the discrepancy in our salaries. Our labor is showily gendered. The men build things; break a sweat and expend lots of energy, run around handling hardware and supplies. I sit at a desk, make phone calls, write emails in French, and make sure the whole program doesn’t go to pieces. Is that where the 5% went? Certainly: everyone knows invisible work is worth less. You don’t notice something’s running if it’s running smoothly. Away from the office, it’s my unspoken task to handle all things emotional. I comfort the homesick; I take care of ill students. I sit in hospital waiting rooms and call home and fill prescriptions. But all that, of course, is a labor of love — and because I’m the woman here, it’s my duty, performed for free.

When I found out about my pay discrepancy, I wondered if it was because our jobs had different descriptions. After all, studio management and business management require different skills. And yet. At this job we all work the same hours. At this job we all have the same experience. It’s an answer almost too simple, too backwards and too old-fashioned to think about: I’m being paid less because my gendered labor is worth less.

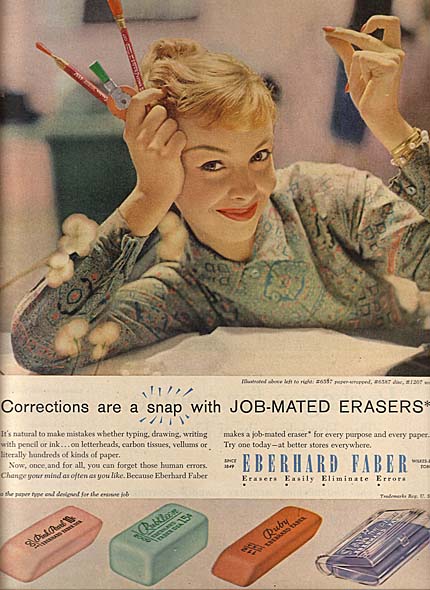

What is women’s work? What is gendered labor? As I write this essay at my desk, in my silk stockings and tailored dress, it’s impossible not to think of the 1950s secretary girl — smartly clad, capable of all things, and very flexible, if you know what I mean. The hegemonic structure of “women’s work” posits us as secret, smooth, and quiet. We are secretarial, administrative, behind the scenes and rarely management. We run the show, but run it from backstage. And above all, a woman’s work is emotional labor. It is being pleasant, and cordial; it is having a “cheerful desk presence” or a “personable demeanor,” it is caring about your students even if some of them are mean and terrible; it is representing, with your entire being, your face and your clothes and possibly your soul: Your Employer, LLC.

One instinct then is to declare: okay, no more women’s work, I’m one of the boys now! Fuck the patriarchy, we’re all humans and a woman can do what a man does but better! But that’s pretty second-wave and honestly, I have no interest in mixing tubs of tempera paint. I know how to use a drill, but I have no desire to go to the hardware store and acquire six of them. I genuinely take a deep and immense pleasure in managing the office. It suits me.

The problem is not the type of labor itself. I am marvelously happy doing this “women’s work,” and I realize the phrasing is problematic. To swap “men’s work” and “women’s work” solves no problems; it’s not about the work but who performs it. The issue is the way in which we gender and correspondingly devalue certain kinds of labor, especially those that lend themselves to invisibility, like administration. It is systemic and pernicious: I catch myself doing it sometimes, when I question my worth as a worker. It’s more than my salary — it’s the nagging sense that I’m not as important, even though I know full well that my position is essential.

So the solution is twofold: raise the pay of historically gendered and devalued jobs to a more equitable level. (This is unlikely to happen in my lifetime.) And respect the people — mostly women — who perform this kind of labor. Because after all, emotional or no: it is labor.

Like social media publicists or gallery girls, a woman’s work extends beyond the duties she is assigned. I recently updated my resume to include the phrase “pleasant demeanor.” Jennifer Pan writes at length on this phenomenon in the excellent piece “Pink Collar.” If the failure of the publicist is her inability to adequately hide that she is performing emotional work for pay, then the tragedy of the desk girl is that her emotional affect is a job requirement. Trawling job listings for the permanent position I will need after this program ends, I find in their requirements the same clusters of “soft skills” intimately tied to women’s labor: “graceful under pressure,” “cheerful and confident manner,” “multitasker,” your mother, best friend, and girlfriend all rolled into one neat package decked out in J Crew or Balenciaga.

A woman’s work is invisible and must appear effortless, which is why she is so rarely adequately compensated. If she has no desire to lean in then she’s certainly not “ambitious.” Never mind that aggression is a learned behavior, and that not everyone desires to perform that kind of showy labor. (It should go without saying that this phenomenon hurts men too, but #NotAllMen, so let me remind you.) The woman worker — particularly in the creative industry in the era of neoliberalism, where her selling points are not only intellectual but psychological and physical — is a shock absorber, the silent laborer, the understood “emotional” creature. It seems natural to delegate the emotional lifting to women: is it any coincidence that gallery girls are well, gallery girls, while art handlers are primarily male? The women flirt with customers and pull sales. The men move around the art.

Yet no one respects these “pretty girl jobs,” the PR girls with glitzy Instagrams or the anxious personal assistants with high ponytails and great wardrobes. On a less glamorous note, think of the teacher or the nurse, who are expected to communicate emotional investment. It is labor. It is labor to perform. It is work and it burns you out in a way that’s hard to relate to others. I come home after eighteen-hour days and am totally exhausted. In fact, at this point I hardly have emotions anymore.

When the students at my program come to me with their problems I am always there to listen and help them out, no matter the hour. I am certain they think it is because I am a nice person. But here is the bitter pill to swallow: whether or not I like my students; whether or not the gallery girl likes her employer’s patrons; whether or not the PR girl cares about her clients — the nurse her patients, the secretary her employer, the woman laboring invisibly under the guise of assumed emotion — we must demonstrate that we care. To take care of students is my job, delegated to me by my position and my gender. It’s a job I do well; one I am happy to perform. But it’s a job, and it is labor, and it is neither adequately recognized nor compensated.

This post may contain affiliate links.