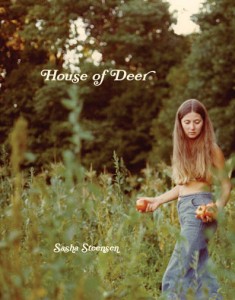

Reading House of Deer, Sasha Steensen’s third collection of poetry is like opening jewelry boxes buried within dresser drawers. She calls on things hidden and precious, a fawn inside a doe; eggs hatching within thoughts; a pearl. Much of the book is composed of small squares of text, centered on the white page — though they’re broken up by longer essayistic sections, including one of the best pieces in the book, “Personal Poem Including Opium’s History.”

By turns aphoristic and impenetrable, Sasha Steensen has an ear for the strange. She can be playful like Hopkins, whom she styles herself after in a poem called “Fragments” and whose name she takes for the family’s street. Neat as Russian nesting dolls, these poems have a cumulative power. The poet builds on the ideas of what it means to be a sister (name dropping Antigone), addiction, what belongs in a poem, and the difficulty of “learning to recognize a story.”

Touching on these different threads of the collection (childhood in rural middle America, tales about deer, memory) Steensen comes at the narrative of a family obliquely. The family is a monolith, unnumbered and never individuated.

The family loved its silo where so many cats drowned.

The family even loved the bats in her belfry.

Until they burned it down

The lyric unfolds around the family always breaking apart and somehow being stitched again. They go “back to the land” and away from it; parents splinter; some members struggle with heroin. They find themselves born again (I think without the religious connotation) and again. The poems’ scope can be unwieldy and the components of the family are ill-defined, though the choice is deliberate. What is withheld from the narrative is in service of an expansive gesture: to describe the machinations of all families, or at least a certain kind of family that belongs to the 1970s. There’s a reach for inclusion, with titles like “The History of the Human Family” and tales of a girl raised by deer. In an early poem, “Family,” Steensen proclaims, “If family is a body, learn its anatomy.” The way the members of the family relate to each other here reminds me less of a single body and more of a hive. The family is firmly rooted in the general and abstract.

It’s an interesting project for sure, but I’m always happy to see the I get up and perform. I have a weakness for confessions of hatred. And Steensen can be pleasingly disagreeable when she wants to be:

I hate the underside

of an idea

but I like the underside

of grass that grows

underwater

The collection occasionally gets bogged down with musings on what it means to tell a story, and she does the meta thing of gesturing to the poem more than I’d like. But when she gets it right, Steensen is exacting and unrelenting. In “Personal Poem Including Opium’s History” the speaker reflects on her history with her brother and his struggle with addiction. There’s a repetition of “You comforted me” which is noticeably self- conscious – she adds dismissively “You comforted me, etc. etc”. She imagines burning, burying, bullying her sentimentality before succumbing. “Or, instead, remember something Claudia once said: / Risk sentimentality or who will care about your damn poem? / You comforted me.”

We should all thank Claudia because the poems become more generous and conflicted when Steensen allows herself to get uncomfortably specific and personal (whether it is fictional is unimportant, but I like a good personal poem as opposed to one of abstraction and intellect). In the first poem of the book the speaker says “hey, Lantern, you cannot keep to yourself / in such dark night / things you wish to hide // why / I can’t say”. That tells us from the beginning the poet is interested in withholding; she teases. For example one of the prosier poems, “Election Day,” breaks off abruptly, “I would have let you in if you had just knocked, / but I’ve spent all the time I have. / There are children to clothe and dishes to do, and it’s just not the kind of poem where everything belongs.”

The expansive, essayistic sections veer more toward the lyric I, while the short stand-alone pieces experiment with language: they collapse the space between words and subsume the speaker. The project would be more cohesive if Steensen could find a way to consolidate these two styles and modes of address. Ultimately though these poems are a pleasure for their small weird gifts and devastating delivery:

to be a sister is to sing while burying

to sing of the tree

of the creek

& of the antlered thoughts descending there to drink

Laura Creste graduated from Bennington College and will pursue an MFA in poetry at New York University in fall of 2014. Her poems have appeared in plain china: Best Undergraduate Writing 2012, the Silo, and elsewhere.

This post may contain affiliate links.