This week, Lionsgate released the teaser trailer for the third installment of the Hunger Games films. Rather than following the genre’s standard conventions and presenting clips from the forthcoming movie, though, this first look at Hunger Games: Mockingjay — Part I instead features a single, animated shot of the gold-colored pendant the protagonist Katniss Everdeen wears in the films: a bird set inside a gold circle clutching an arrow. While dramatic music plays, a small fire grows against a black background, eventually forming into the mockingjay symbol. Once fully constituted, the bird twists free from the circle surrounding it, rotates to face the camera head on, and then spreads its wings wide, engulfed in increasingly dramatic flames all the while. With a loud bang, the movie title, also in flames, falls from above to land beneath the mockingjay and the music stops. This pyrotechnic display takes just under thirty seconds. For the remaining twenty seconds left in the trailer, the mockingjay continues to face defiantly ahead, burning briskly, the only soundtrack the crackle of its flames. Similarly, rather than depicting individual characters or stills from the film, the posters for Mockingjay mirror this imagery, with the now-iconic bird at the center engulfed by a bonfire that apparently emanates from within.

The early promotional materials for the movie thereby codify fire as of central importance to the series. On its most obvious level, the iconography calls upon the classical tale of the phoenix, a mythical bird reborn from the desiccated ashes of its predecessor. Given the plot of the Hunger Games films — namely that of a populist uprising dedicated to overthrowing a totalitarian regime — this comparison has much to recommend it. Like the mockingjay, the phoenix is frequently pictured within a circular nimbus. Moreover, Suzanne Collins, the author of the books upon which the films are based, has claimed that the Roman gladiator battles were one inspiration for the novels. Yet despite these similarities, analyzing the mockingjay as a riff on the figure of the phoenix elides the revolutionary content of the films. While the two may share some common ground, revolution, unlike rebirth, is predicated upon toppling a previous order and replacing it with something altogether different. The American Revolution provides one object lesson in this process. When a member of George Washington’s forces, Colonel Lewis Nicola, suggested that Washington crown himself King, the future first president of the United States harshly rebuked him. In a letter in response to Nicola, Washington wrote that the desire to cast off King George’s tyranny only to replace him with another monarch represented “the greatest mischiefs that can befall my Country.”

Those revolutions that merely install a system that recapitulates the former status quo are typically seen as insufficient uprisings, not properly revolutions at all. Instead of this classical antecedent, then, the fire imagery in the Hunger Games films and advertising campaigns conjures up a more material and immediate referent: the use of self-immolation as a form of political protest.

The act of setting oneself on fire to protest current conditions looms large in the U.S. imagination. Though the practice exists in a wide variety of cultures and has several historical origins, it has frequently been associated with Eastern religions. This is particularly the case in the United States where many audiences were introduced to the tradition during the Vietnam War when Buddhist monks set themselves aflame to protest their treatment by the U.S.-supported government of South Vietnam. These immolations were widely documented and piped into hundreds of households throughout the United States during the Vietnam War, the first televised military conflict, where astonished families watched the spectacle on their television sets. These segments were interspersed with footage from the war itself. The televisual nature of the war in Vietnam has two implications for self-immolation and the Hunger Games. First, while this kind of political martyrdom had specific and unique meanings within the various cultures in which it was used, ones that very likely evaded Western viewers, the meanings of politicized self-immolation in the United States became closely linked with spectatorship. Relatedly, these audiences came to associate such burnings with certain racialized bodies seen as in conflict with the United States and its interests abroad.

These meanings, implications, and values contributed to the coverage in the United States of a more recent series of conflicts: the Arab Spring. As reported by many major news outlets based in the U.S., self-immolation provided the “spark” for the uprisings that erupted across the Middle East starting in 2010. On the morning of December 16 of that year, Mohamed Bouazizi, a Tunisian street vendor struggling to make a living selling fruit, was allegedly reprimanded and then slapped by a municipal inspector. When Bouazizi’s demand that his confiscated property be returned to him was twice denied, he covered himself in paint thinner and then set himself ablaze in front of the governor’s office. Bouazizi’s protest spread, with the unemployed and disenfranchised mimicking the action. The U.S. media picked up on this thread, frequently illustrating news articles with photographs of protests and government crackdowns that featured large bonfires burning prominently within the frame, or using footage of explosions and burning buildings as newscasters in voiceover reported on events.

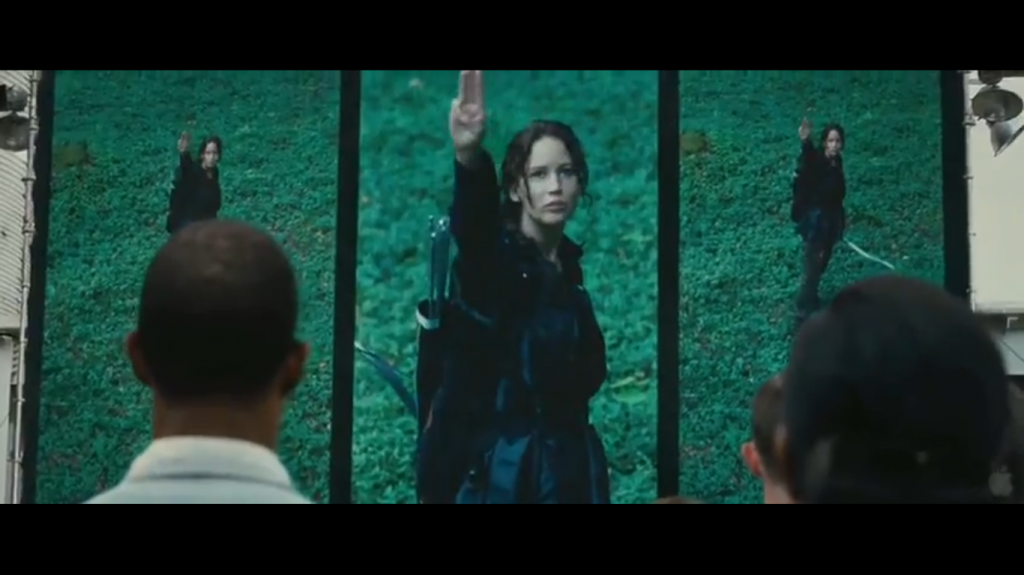

Katniss shares several similarities with this cast of characters. Like Bouazizi, she is forced to eke out a difficult existence within a repressive state that doles out vengeance without the limits of jurisprudence or civil protections. As a participant in a perverse reality TV show and its reluctant hero, Katniss’s movements are meticulously documented on camera and watched by audiences across Panem, a fictional and dystopian representation of North America. And perhaps most saliently, Katniss’s claim to fame, even before winning the 74th Hunger Games, is that she is literally and figuratively the “girl on fire.” Thanks to the talents of her costume designer, Katniss frequently wears outfits that engulf her in flames: she burns, but does not succumb to the inferno. Katniss’s reluctance to kill her fellow competitors during the Games, her open mourning for the slain contestant Rue and reverential treatment of her body, and her attempt at suicide to avoid battling the final surviving contestant — and her pseudo-lover — to the death, endear her to audiences and transform her into a symbol of revolution. Though Collins wrote the books well before the start of the Arab Spring, both of the first two films were shot after the protests began. Perhaps unsurprisingly then, the visual echoes between the news coverage of the uprisings across the region and the film are striking: both figure paratroopers or police in riot gear as the avatars of a repressive state, both prominently feature fire and destruction in their images, both favor photographs and stills of large crowds waiting for a signal, and both dwell incessantly upon acts of spectatorship. Finally, both groups are associated with a resistance to U.S. might. Many of the regimes toppled during the Arab Spring came to power with the support of the United States. And while the Hunger Games takes place in a post-national alternative realm, the actors playing the characters who live in the Capitol all speak with U.S. accents.

Survival aside, Katniss’s gender and race, at least in her corporialization as Jennifer Lawrence, mark her as distinct from these real-world analogues. Though women, too, have participated in ritualized burnings to protest their conditions, many of the most famous recent examples are male. Though at times Peeta Mellark, the other so-called “tribute” from Katniss’s home, burns alongside her, he apparently is incidental to the theatrics. He is never dubbed the “boy on fire” and he fails to signify revolution in the ways that Katniss does.

Theorist Gayatri Spivak’s work gives one unexpected turn to Katniss’s gender. In her now-canonical article “Can the Subaltern Speak?” Spivak discusses the Hindu practice of sati, a ritual in which a recent widow immolates herself on her husband’s funeral pyre. Spivak uses the example to illustrate, among other points, the various ways that the agency and voices of colonial and postcolonial women are doubly constrained, first by imperialism and then by autochthonous systems. Turning to the archive, in her final section Spivak argues that Hindu and British colonial texts obscure the meanings of sati for Hindu women themselves because these texts can only recapitulate women’s experiences to already dominant narratives and meanings. This leads Spivak to her controversial conclusion that the subaltern cannot speak.

Katniss, too, is in some ways obscured by her flaming performance. She receives the nickname “girl on fire” due to a televised performance but throughout the first and second films she is only referred to by this moniker when she is within the Capitol, the seat of power in Panem, and therefore on display ostensibly to confirm the Capitol citizens’ biases and prejudices. Her assumption of the guise of self-immolator, then, is separate from her authentic self and in some ways masks it. Despite her insistence that she does not want to be a symbol of resistance and revolution, that she just wants to live a private life, the meanings of Katniss’s actions are apparently beyond her control. Indeed, the films go to great lengths to show us that televisual images confirming dominant narratives are usually inaccurate: Katniss’s love affair with Peeta is as much a survival strategy as it is an indicator of her actual feelings, and characters who seem publicly to support the Capitol’s regime turn out to be those working to undermine it.

When audiences watch the Hunger Games films and see, even if only dimly, the glimmers of the Arab Spring and other imperial conflicts, they also see the limitations of the mediums by which they consume these struggles. When Katniss lights herself on fire, the part of herself that is lost forever, the part that burns away, is inextricable from the spectator’s ability to read her actions as the beginning of revolution.

This post may contain affiliate links.