Tr. Daniella Gitlin

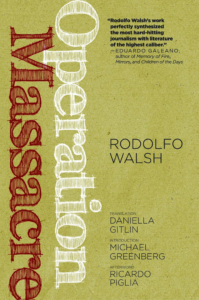

June 9, 1956 in Buenos Aires, a small rebellion tried and failed to reclaim Argentina for ex- (and future) President Juan Perón, nine months after he had been ousted in a coup. That night, amid a series of actions that popped and fizzled around the city like scattered fireworks, police forces collected 18 men from an apartment, drove them to a peripheral neighborhood, lined them up, and executed them — sort of. The following year, journalist Rodolfo Walsh published the incredible story of that night’s execution, which, as it turned out, was botched. Seven of the men lived. Operación Masacre, which Walsh managed to publish piece by piece the following year in the only magazine whose editor was brave enough to run it, is the story of the seven survivors, the events of the night, and Walsh’s quest for truth and justice as his belief in even the possibility of those values turns more and more to ruins. Operación Masacre has long been recognized as one of the foundational pieces of investigative journalism; more than fifty years later, Operation Massacre reaches an English-speaking audience in this clear translation by Daniella Gitlin.

The events that form the backbone of Operation Massacre are almost incidental — as Walsh himself is the first to admit, they are neither the first, the worst, nor the last of the atrocities committed in the name of revolution or order. The men who were arrested and shot were suspected of being Peronist militants involved in the night’s rebellion. As Walsh explains in exquisite detail, they were gathered in an apartment far from the action listening to a boxing match; while some of the men were Peronists and sympathizers, many were not, and almost none of them were directly involved. The story is exemplary in all senses of the word — it both stands out and does not stand out as one of countless atrocious acts of violence and repression that have sprung, seemingly spontaneously, out of no particular intention, but rather a culture of violence, fear, and general repression: “The June massacre exemplifies but does not represent the height of this regime’s perversity. Aramburu’s government imprisoned thousands of workers, stifled each and every strike, and did away with union organizing. Torture became the norm and spread throughout the entire country.”

Perhaps more compelling than the story of that night in 1956, or the story of the successive dictatorships that gripped Argentina for decades, is the story of Walsh himself, woven, almost unwillingly it seems, throughout the story of the men who survived execution. The narrative is laced with Walsh’s growing sense of just how fruitless his task is — and yet he holds on. He fixates on the details of the events with exquisite care and courage. At points in Walsh’s dogged pursuit of what sometimes seem like unimportant minutiae of that night, the reader has to think, what is the point of all this precision? Walsh knows as well as we do — and certainly as well as his contemporary audience did — that justice will likely not be served, but that death very well may be. And yet that is a large part of the virtue of Walsh’s narrative, and what has made his voice into a paragon of journalistic and civil integrity: Walsh sees the world as it is, but he never loses sight of the world as it should be.

Beyond providing English-speaking readers access to Walsh’s search for truth, this edition of Operation Massacre brings us through the publication history, including the Introductions and Epilogues for each edition of the book published during his lifetime. Through these, we see Walsh’s tone change as the years pass and nothing changes. At the end of the original Introduction, Walsh writes: “ . . . I happen to believe, with complete earnestness and conviction, in the right of every citizen to share any truth that he comes to know, however dangerous that truth may be. And I believe in this book, in the impact it can have.” In the Epilogue to the 1964 edition, he writes: “In 1957 I boasted: ‘This case is in process, and will continue to be for as long as is necessary, months or even years.’ I would like to retract that flawed statement. This case is no longer in process, it is barely a piece of history; this case is dead.”

Walsh thought his book could bring some justice or recognition or understanding to people. And perhaps, even after years passed and no official justice or restitution came, he still thought his book could have an impact, if only to show people the hideous, crushing waste he saw in revolution:

If there is one thing that I have tried to evoke in these pages it is the horror of revolutions, whose first victims are always innocent people like the executed men at José León Suárez or that dying soldier just a few meters from where I was. These poor people do not die screaming ‘Long live the nation’ like they do in novels. They die vomiting from fear, like Nicolás Carranza, or cursing others for abandoning them, like Bernardino Rodríguez.

One of the most striking things about Operation Massacre is that Walsh is not radicalized, but only becomes more committed to the values of democracy and respect for human rights that he believes should be essential. We must remember that the writer of this passage is both the man who was involved with Peronists, even the militant Montoneros at points, whose Montonera daughter killed herself in the midst of battle with government forces, as well as the man who, walking to his home on June 9, 1956, saw a young man die in the street screaming to his comrades, “Don’t leave me here alone! You sons of—, don’t leave me here alone!”

Most heart-breaking, most incredible, most damning and beautiful, is the piece of writing that finally got Walsh murdered. Included in this translation of Operation Massacre is Walsh’s other best known work, “Open Letter from a Writer to the Military Junta.” Walsh sent the letter to newspapers on March 24, 1977; a day later, he was seen for the last time, being picked up on the street by a “Work Group” (death squad). In the letter, Walsh recites a list of facts about the Junta’s treatment of the Argentine people — the transformation of the economy and society that sent working people back to colonial conditions, turned the cities into slums, and shrouded the country in terror — simply and elegantly linking state terror and the extreme, neoliberal economic policies that fueled it. The closing words of his last piece of writing ache with Walsh’s unshakable devotion to truth and the profound fatigue of watching a lifetime of this devotion come to nothing: “These are the thoughts I wanted to pass on to the members of this Junta on the first anniversary of your ill-fated government, with no hope of being heard, with the certainty of being persecuted, but faithful to the commitment I made a long time ago to bear witness during difficult times.”

Alli Carlisle is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at UCLA.

This post may contain affiliate links.