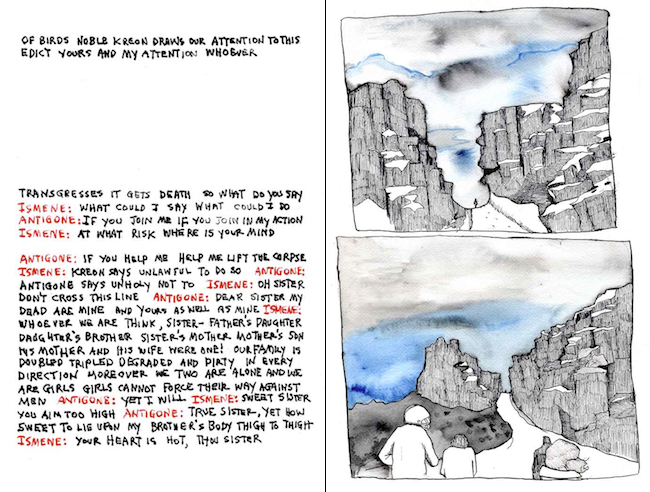

Antigonick is the newest book by the poet Anne Carson, and like Nox, the exquisite accordion book released by New Directions in 2010, it presents a new way of thinking about the book as a literary and artistic medium. A collaboration with illustrator Bianca Stone, Carson’s former student, and designer Robert Currie, who is credited as assisting with the design of Nox, Antigonick is an unconventional translation of Antigone, Sophocles’ tragedy about the willful, intractable girl who transgresses against her uncle the King of Thebes’ royal decree by burying her dead brother, a political traitor, according to the divine rites. The text is hand-lettered by Carson in black and red ink, and the color illustrations (they look like watercolor and ink, but the media aren’t recorded) are printed on vellum so that they overlay the text. The visual motif of a spool of thread runs through Stone’s illustrations, and like the thread the images are placed so they can get tangled up with the text. It’s a brave and interesting project, but one that, in spite of Carson’s fiercely intelligent creative instincts, doesn’t actually hold together.

If you’ve spent time with Carson’s work you know that as a translator she is unmistakably a poet. She’s done so-called straight translations from Latin and Greek, but much of her work is about the way translation never comes out straight at all, how it takes you inside of language instead as through a spectacularly winding corridor and into lushly spacious emotional possibilities. Her poetry is expressionistic (you see this in Antigonick), shot through with a spiritual turbulence and an almost violent sensitivity to experience, and the barbed edges of her lines can send shocks through you. It’s a little like reading Louise Glück in this way, but Glück’s images can feel so sharp they’re like switchblades through your imagination. Carson is just as emotionally uncompromising, but she’s wry and funny, too; the humor might be Beckettian in its existentialist stance, but it’s mischievous and it makes you laugh. As a poet and as a translator, she’s always opening doors in surprising places.

Antigonick is a strange book for Carson because, unlike Nox, or If Not, Winter, her translations of the complete fragments of Sappho, or Autobiography of Red, her luminous verse novel re-telling of the Greek myth of Geryon, to all of which Antigonick bears formal and thematic resemblances, it doesn’t fully open up the door to its source text for the reader. Instead, it demands prior knowledge of Antigone in order to really plumb the depths of the work. It’s not really a translation — it’s a re-imagining, what Carson’s Canadian contemporary Erin Moure calls a “transcreation,” with both text and images and the interplay between them transposing Sophocles’ language and themes. The problem is that the work comes alive in spectacular ways only when you put it next to a more traditional translation. (I used Robert Fagles’ with notes by Bernard Knox.) A classicist friend of mine commented that her undergraduates would find Antigonick a fascinating companion text to Sophocles’ play, and I bet that’s true, but I’m not sure it’s a strength. Antigonick strives to be a multi-dimensional artistic work, not a study of or a gloss on Antigone. This is the first book of Carson’s in which I feel her scholarly impulse barricades textual meanings. Usually it provides a generous way in.

The other problem is Bianca Stone’s illustrations. They form a parallel text to Carson’s translation; the visual motifs — spools of thread, bleak winter landscapes, horses, groups of figures with cylinder block heads, quaint domestic interiors with quilt-covered beds and floral rugs — have no literal connection to the linguistic images. That would be fine, except that I think they lack the depth, in both subject and style, to dovetail with Carson’s translation. The interactions between image and text with the vellum overlay is clever compositionally, but the connections feel so tenuous — you really have to reach for them, and even then you’re not satisfied with what you shore up. Carson’s work is so erudite, and Stone’s so elliptical, that the composite effect is frustratingly opaque. I can’t help thinking that more interesting illustrations would change the way I read Carson’s text, that the illustrations could help pry open that closed door. Instead they add another layer of mystification, and the book hobbles as a result.

Antigonick doesn’t ultimately work, but when you begin to give it the kind of scholarly reading it demands, you find it has moments of brilliance. (That is, Carson’s text does; Stone’s illustrations at best have moments of cleverness.) There’s a lot to relish here. And the idea of doing Sophocles as a graphic novel of this sort is kind of ingenious. Artist books, at their very best, are little theaters: they take a literary text and give it sensory life on the page. What Carson, Stone, and Currie provide together is actually a staging of the play in book form. (Carson reinforces this effect by prefacing the play with a list of its “cast” and a description of its “set,” terms found far more often in theater than in literature.) It’s thrilling to see Carson, after nearly thirty years of published work, turn her attention to the creative possibilities of the book as an artistic medium. What Antigonick showed me is that Carson can impress me, even electrify me, even when I think she gets it wrong. That’s one of the highest tributes I can pay an artist.

This post may contain affiliate links.