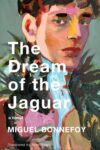

Things: A Story of the Sixties

Things: A Story of the Sixties

& A Man Asleep

by Georges Perec

translated by David Bellos and Andrew Leak

[David R. Godine; 2011]

The biggest promoters of Georges Perec’s first novella may not have actually liked it. Lefty critics and apparatchiks helped Things: A Story of the Sixties make the leap from Paris to Eastern Bloc French classes, and they tended to treat it as an indictment of capitalism, not an intrinsically enjoyable story about kids with shopping fantasies. An exception in this red and pink crowd was an unimpressed reviewer from the Communist paper L’Humanité who considered it a pornographic portrait of consumerism. Maybe he had a rough time dealing with the montages of shop windows and “cupboards, in light-coloured wood, with fittings of gleaming brass…” In any case, by the time he starts quoting Lenin, he inadvertently suggests why the novella found success elsewhere as social commentary: it’s as if its value were indexed against some unrealized work that could convey all the present’s political imperfections, lighting the way toward a just future.

Readers in a revolutionary mindset may be unable to fully love and unite with the current moment. In that case they have at least one thing in common with Perec’s literary output. His narrative frames and the people who live in them tend to look fragmented; but it’s this incompleteness that invites pathos and attempts to piece a puzzle back together.

In Things, this disaffection is on majestic display in the main characters, which, come to think of it, are the furniture, clothes, and food. Jerome and Sylvie are market researchers who feel unfulfilled without all the stuff their advertising colleagues tell them they crave. On the odd night, they can almost be happy buying used shirts or playing cards with their friends, and there’s a blissful fullness to the present.

But then the liquor wears off, and redemption drifts away again.

“The film they would have liked to live” haunts them one night as they leave disappointed from the cinema, an apt metaphor for the vision that seems to loom wherever they go. Even when they run off to Tunisia, it’s all they can do but to quietly take in the expanding vistas of the desirable and out-of-reach: rockets, trains, money — an entire planet to themselves! One future day, their apotheosis could happen while they’re in gigantic palaces: “On vast scaffolds, ten thousand brasses played Verdi’s Requiem. Poems were picked out on mountainsides. Gardens sprang up in the desert. Whole towns were nothing but frescoes.”

The fantastic montages and lists are a major selling point (Perec was an archivist by day and a Flaubert fan off the clock), but this same tendency to summarize also makes the narration eerily distant. Maybe it’s possible for a pair of people to build their existence and sense of worth around appropriating some marketers’ vision of plenitude, but overall, Things feels less like life than something cherry-picked from it by an invisible sociologist obsessed with status and careers. The couple never kiss or otherwise acknowledge an intimate domestic side in view of the “camera-pen.” Until close to the end, we’re almost never privy to their conversations.

Then again, the almost total lack of dialogue could just be the pregnant silence of two hungover kids:

They would feel empty and stupid… as if the very impulse which had made them drink had only reawakened in them a much deeper perplexity, a more hermetic contradiction from which they could not abstract themselves.

The narrator’s attention goes elsewhere, and in the negative space of unanswered questions we can identify with their situation, transfixed before a book that’s as much a spectacle as Jerome and Sylvie’s fantasies — and barred, like the two of them from understanding what’s in front of us.

The narrator’s attention goes elsewhere, and in the negative space of unanswered questions we can identify with their situation, transfixed before a book that’s as much a spectacle as Jerome and Sylvie’s fantasies — and barred, like the two of them from understanding what’s in front of us.

At least this feels true in the afterglow of A Man Asleep, Perec’s third novella (now conveniently packaged in one volume with Things). For the guy in this story, all pre-existing concepts lose their legitimacy and start looking like arbitrary specters standing between him and the experience of the everyday. As he sits indifferently on his bed, a narrator who may or may not be the same person addresses him(self?) as “You.” “You” isn’t leaving his apartment to go to some testing room where he’ll regurgitate rarefied social theories:

You will not set down on four, eight, or twelve sheets of paper what you know, what you think, what you know you are supposed to think about alienation, the workers, modernity and leisure, about white-collar workers or about automation, about our knowledge of others, about Marx as a rival of De Tocqueville…

“You” ignores the notes from the University and his friend knocking on his door. Instead, he’s off on a dérive (or fugue?) through Paris, perpetually on the verge of a clean break with all myths and obligations except one: embracing the silence hiding between the words and articulated structures around him — a fixed point in a turning world.

With this goal, most of the tension for “you” (and us) stems from the trouble of finding a descriptive language or non-arbitrary frame of mind — as if “your” gestures, “your” greasy meals, “your” wine, “your” wandering could start being themselves, free of the taint of adjectives, metaphors and historical associations. Images keep returning in the midst of this disjointed search, blocking the path:

You must be precise, logical. Proceed methodically. There comes a point when you must, at all costs, be able to stop, reflect, really weigh up the situation. If there is a lake in the middle of your head, a possibility that is not only plausible, but quite normal, even though it may not be asserted without qualification, then it will take you a certain amount of time to reach it.

It rains at the end of A Man Asleep, a soaking, cold reminder of a reality that keeps flowing regardless of any imaginary critiques or truth procedures. It’s also an apt symbol of the historical context that gave birth to these two novellas. A manifesto that may ironically call to mind fewer concrete situations than this pair of Perec works, the Situationist Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle appeared at almost the same time as A Man Asleep in 1967, denouncing modern industrial life as a repressively entertaining multimedia prison. Suspicion of markets, states, traditional families, pretty pictures, and other hierarchies was mounting in France, and by May 1968, students were erecting barricades and #occupying large swaths of Paris’ Latin Quarter. The largest general strike in history was soon underway.

Perec’s work seems to coyly represent and play in this cultural landscape while remaining noncommittal and oblique. This could make sense given his background. Nazis killed much of his family — and his most serious long-term intimate relationships were with crosswords and baroque literary constraints. Possibly a conscious response to the dangerous fickleness of history, the ideals his muted portraits openly evoke are esoteric and formal. He once wrote an entire novel in which the only vowel was the letter ‘e’ and still managed to say quite a bit. “Je cherche en même temps l’éternel et l’éphémère” (“I search at once the eternal and ephemeral”) is a line from Les Revenentes, which was later recycled as the epigraph for chapter 99 of his magnum opus, a meticulous log of an apartment’s atomized residents and all their stuff frozen (as if they were paused in a film) one evening. That expansive novel’s title, La Vie mode d’emploi (Life: a User’s Manual), could also be an (in)appropriate way to describe these two compact stories that preceded it.

Percival Bartlebooth is one of Life’s apartment dwellers and his routine mirrors this blend of beauty and nihilism pervasive in Perec. “Faced with the inextricable incoherence” of the world, he decides he’ll spend the rest of his life painting watercolors. The five hundred landscapes he paints at ports around the world are turned into five hundred puzzles, which are intended to be turned into five hundred blank sheets of paper that show no trace of his project’s existence.

Percival Bartlebooth is one of Life’s apartment dwellers and his routine mirrors this blend of beauty and nihilism pervasive in Perec. “Faced with the inextricable incoherence” of the world, he decides he’ll spend the rest of his life painting watercolors. The five hundred landscapes he paints at ports around the world are turned into five hundred puzzles, which are intended to be turned into five hundred blank sheets of paper that show no trace of his project’s existence.

With A Man Asleep as a chaser, the effect of this smaller two-story volume may have a similar negating effect: giving money, politics, fashion, and whatever else a contingent and absurd quality next to an ineffable Real.

Depending on what puzzle pieces you’re holding, this portrait of rigorous anomie could not only be enjoyable in itself but also pregnant with its opposite. If nothing else, Perec can become a pretext at this point, a convoluted Rube Goldberg device for suggesting love and organic solidarity through omission. Maybe this is what drew State Socialists to Things. A picture of harmonious unity in the West could have harmed the project of continued revolution; instead, Things — like Perec’s other works — can provide a nourishing negative-image of an ideal that has yet to find a physical form.

Say you buy the notion that anomie can be pregnant with its opposite and also think that some wholeness can’t be directly expressed in words. Yeah? Then maybe Perec’s novels could help you, like, get it going in your personal lifestyle. All you may have to do is invoke the scenario you’re trying to avoid.

“I’ve been reading this novel,” you might say to a special friend. “These kids Jerome and Sylvie could be happy with themselves. But there’s no love lost between them. At least that we can see.”

The inspiration for the next lines may have to come from outside Perec’s chilly vision of the world.

Stephan Crown-Weber is a freelance writer based in Danville, Kentucky.

This post may contain affiliate links.