These death masks are interesting. But why? Comparing the oil renderings of Dante against the plaster molded contours of his visage don’t teach me anything about his poetry. I hold a quarter up to the mask of Washington and I see discrepancies. Maybe I see a pattern of discrepancies. But do I see meaning?

These death masks are interesting. But why? Comparing the oil renderings of Dante against the plaster molded contours of his visage don’t teach me anything about his poetry. I hold a quarter up to the mask of Washington and I see discrepancies. Maybe I see a pattern of discrepancies. But do I see meaning?

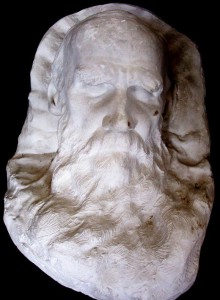

An emaciated Walt Whitman, still inhabited by the presence of life in the image of death—in other words, still contradicting himself. But now I’m just projecting the works onto the physical body of the artist. That’s not Whitman’s face, it’s a math teacher from Akron. It’s a child molester. It’s your uncle.

We have a biological affinity for faces. Also, personalities and, for that matter, gossip. We love gossip. Whitman might have called the news he brought to America about itself the Holiest kind of gossip. It’s still being discussed in Zuccotti Park.

But Whitman’s power wasn’t in his face. Neither was the power of Keats. Tolstoy might be the only one in the lot to claim that our skin is more important, powerful, and blessed than the work. Whitman would dreamily emphasize the OUR in ‘our skin.’

But these aren’t even real faces. They’re not human bodies with sensory nerves being tickled and burned and titillated, which is the heart of the matter. Our strongest inheritance, the works, contrast sharp against the weakest, ourselves. Oh yeah, that’s why we write! Because time is running out. These aren’t masks. They’re scoreboards from games played long ago and the clocks all still read 00:00. Momento mori.

Jokes considered for, but not used in this post:

“The masks remind us that you can’t save your own skin.”

“There’s a mask in an attic somewhere getting younger.”

This post may contain affiliate links.