[Four Way Books; 2018]

I’ve had Monica Ferrell’s second collection of poems You Darling Thing on my desk for a spell. Delays can happen when circumstances encircle us. Life takes over in the form of unexpected work, the needs of loved ones, and unplanned travel, to name a few. As I write this review I am home in the stillness of quarantine with my husband and three children — no fixed measure to the end of this stasis, neither by days nor precise restrictions, which are ever-dynamic & now (suddenly) we must all mask ourselves in public. If we stay at home does the sidewalk out front count, or is that a dangerous borderland? Should we instead remain inside with the doors locked, in our rooms, in our beds? As I reread the poems in Ferrell’s You Darling Thing in this unprecedented moment, I see her lines anew, perhaps as they have always been; what I mean is that Ferrell’s lyric experiments were waiting for me for this particular instance of inwardness.

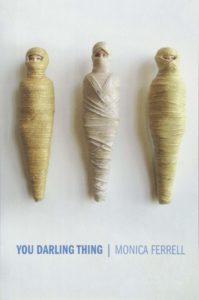

Whereas my earlier encounters with the book’s cover image of artwork by New York-based artist E.V. Day — three mummified Barbies, almost mistakable for spools of thread, whose luscious-lashed blue eyes and immediately surrounding pink skin are their only body parts on display — seemed strange, beguiling even, now I read the trio as what could be a metaphor for me and my other selves all desperate to break free. Our limbs are tied down, our bodies wrapped, with what turns out to be twine and beeswax (materials of industriousness) going up to and past our faces, which are almost entirely masked for our safety and for the public’s too. There is something satisfying in the clarity of this visual — we have no margin for movement, no wiggle room. Or could this image invoke me and my neighbors — the people who live nearby, I mean; the people I always took for granted — the three of us symbols for the rest of everyone tied up by the domestic and kept out of circulation? We are all stay-at-home Barbies now in our isolation, spools of thread at the service of the three fates, and we are the storytelling of the before and the after.

The tension between tragedy and what precedes it, between community connection and the lonely self, between life and death, between memory and forgetting, between “here & there” is taut in the opening poem “This Date”: “This time we’ll come gloved & blind-/folded, we’ll arrive on time” and “This time we’ll be tied down. / We’ll cry out” and “We’ll only smoke if surprised / by tragedy’s approach” and “We’ll grow improvident & stop believing // there was ever such a thing / as alone.” The repetition of “this time” reminds us that we’ve been here before, but for some reason we can’t remember. “This time we’ll forget” — and we will.

The poem that follows speaks to the ache of loneliness the speaker, or any of us, can feel and strikes a prophetic note in the context of our global COVID19 crisis:

THE WAVES

Old men on fourth-story balconies stare down at me,

Children pass by playing ball.

A mother takes in her plain tablecloth, frowning.

I will die

If before nightfall no one touches me.

There is a hospital in this town called Gli Incurabili,

They will take me there and lay me down on the bed like an ivory blade.

I will be pure as a virgin offering empty hands to Christ

And the world will throb beneath me like sea’s blue beneath its white.

There are several poems with the word “bride” in the title, as well as other words indicative of marriage themes such as “husband” and “bridegroom” and “betrothal” and “epithalamium.” One may be eager to make a connection between marriage and the isolation of quarantine here, which seems apt. Ferrell urges us to explore the bride as an archetype, a figure that reappears across history in stories, paintings, and all manner of artifacts that shape culture and, she dares suggest, individual behavior. In “Invention of the Bride” the speaker intones solemnly: “In the memory palace, the dead / Take short breaths. / Shamans breathe a name for who I am.” In “Savage Bride” the temperature rises — “You move in me like the tongue in a mouth” — while “The Tourist Bride” offers a seductive hiss: “Cats, fevered, untranslatable, / Go long ways for secrets and fish heads” and “I feel the feral marble machine of my heart / Leak mercury.” Most brides are, after all, not married yet.

“The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even” is an ekphrastic text after Duchamp’s eponymous artwork (also known as “The Large Glass”). The poem’s nine numbered sections coincide with the nine bachelors in Duchamp’s piece and thus the bride speaks to and of each of the men: “2. You fell asleep in the temple as a boy / Woke up with a heart of stone.” And: “6. I do not hope to meet his face anymore. / I have turned his body into a cold and rigid door.” “The Sleeping Husband” is no less dire: “Nothing to eat here but beer and more dark. / The shower where someone’s young wife died / In an explosion of epilepsy while he slept.” In “Bride of Ruin” both an older woman and the ancient town of Aphrodisias are addressed — “You’re a ruined town too, or nearly, / Hair dissolving to gray” — and here the secret power of the never-wed bride may be further impressed: “Did you love men so much you couldn’t choose / Or love them so little you didn’t care?” Marriage ruins all the fun, as confirmed by the final line of “Epithalamium”: “Still, no one wanted to talk to the newlyweds.”

Three poems in You Darling Thing share the same title — “In the Fetus Museum” —and Ferrell’s “Notes” tell us the lyric triptych responds to Peter the Great’s collection of fetal oddities in St. Petersburg’s Kuntskamera, Russia’s first museum. The three studies of the unborn dotted across the book call to mind the mummified Barbie trio on the cover, a corresponding arrangement of capture. The poetic voice describes each museum fetus with delicate attention and makes a connection between what is “against the glass” and the “world”: “he’s not missing much — except everything. / The inventions of lust, the pageantry of what.” In the second study the poetic voice tries to assure the fetus through direct address — “It’s not too different / outside: here, love is a currency everyone wants. / Where I am, you can’t get enough of touch” — and in the final poem the poetic voice compares the fetus she is observing to a moment in her own life with a beloved, a moment that may never come to be (born): “For his unopening mouth, near pinpricks / Which dictate in faint constellations whiskers / That never formed — seed-points” that are “Like Laika left trailing in space” and “your diffident / Silence to my last letter, or that breath which stops / My saying what swims me too, unhurt and whole.”

Despite the three figures on the cover, the collection opens with two epigraphs, not three, which makes me feel something has been left unsaid. Or perhaps it is Ferrell’s invitation for the reader to fill in the blank. The first epigraph comes from Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, first published in book form in 1878 — specifically the moment when Vroksny is speaking to his horse and calling her “sweetheart” — and the second from Czeslaw Milosz’s 1978 poem “Notes”: “Note #15: STRONG OR WEAK POINT You were always ready to fall to you knees! Yes, I was always ready to fall to my knees.” I’m not sure what to make of these two choices, other than that they point to some kind of appreciation of surrender, and that the epigraphs come from texts published one-hundred years apart, which highlights the passage of time. We’re far from 2078 and who knows what the world will look like (what future museums and history books and poems will have captured then), so I think it is important to offer a third epigraph now.

But before I do, I want to linger on Ferrell’s appreciation of, and invitation to, surrender, which brings me to how the violence against and domination of the female (“sweetheart,” You Darling Thing, “Savage Bride,” “Arachne,” “Emma Bovary”) by the male (Vronsky, author-poet-artist like Tolstoy-Milosz-Duchamp, “Invention of the Bridegroom” who will “blindfold you”) is folded into the epigraphs of Ferrell’s collection, the cover art, the collection’s title, and the poems themselves, as well as how they are named. Ferrell is deeply interested in the female at the mercy of her male counterparts and our patriarchal society, and she shows how violence can even be self-inflicted, especially through language. In “Oh You Absolute Darling” the poetic voice is taken over by an incantation of “verbatim statements made to the author over a period of time by an erstwhile companion,” the words wrapping around her like the twine tying up the Barbies on the book’s cover (“not exactly a barrel of laughs / so much as a barrel of erections” and “Gypsy-themed Barbie doll” and “basket of sexual fruits”). Ferrell explores the consequences of surrender, the aftermath and archive of violence and domination, whether physical, psychological, social, or economic. The repeated figure of the bride bound for marriage calls to mind a recent Op Ed by Kim Brooks, who notes:

how peculiar it is that it is only through divorce that the work a wife has done as a primary caretaker is given a monetary value. This comes in the form of what used to be called alimony and is now called maintenance. These settlements, the lawyers say, are meant to be “rehabilitative.” I’ve always thought of rehabilitation as a process involving one’s recovery from injury. In this case, the injury is marriage and motherhood.

Brooks’ meditation puts Ferrell’s bride and fetus poems in a stark new light.

Ferrell explores surrender in the context of love in “The Tiger Abandoned at the Hunt’s End”:

Blue that knows with it is for me to give

My whole self up in surrender

And I fell in love, ah

My bridegroom

Irretrievably and always, till long

After I heard your boots' steps fade away from this place.

One could do a sustained reading of Ferrell’s You Darling Thing through the lens of blue surrender and forever love unfolding during quarantine where women, mothers, female life partners, and caretakers are finding ourselves at the end of our ropes (it is no small irony that I type this on the eve of Mother’s Day in the United States, a day that is vexed for every woman I know). In “Fuck the Bread. The Bread Is Over.” Sabrina Orah Mark questions her quarantine-time frustrations around not having a “real job” — by which she means work outside the home in the public sphere with a paycheck and the status that comes with “the whole stupid kingdom” — and yet, she considers the following: “The new world order is rearranging itself on the planet and settling in.” But is it? Or is that the stuff of fairytale, especially when domestic violence is up and it seems unlikely that caretaking will ever be valued — whether it’s the caretaking of our children, homes, elders, the weakest among us, or our planet? Why should we surrender? And if we don’t? What if we do, but not in the ways it’s been done before? These questions linger, too, across the pages of Ferrell’s book.

I want to take Ferrell’s invitation, or provocation, to surrender seriously. If I were to offer a third quote to welcome readers as they dive into You Darling Thing — and in the spirit of creating further conversation with the three mummified figures on the cover who can’t speak because their mouths are covered — I would nominate an excerpt from the song “Be a Body” by the musician Grimes, aka Claire Elise Boucher, who has recently been tied up by the process of incubating a child fathered by Elon Musk and documenting her experience on social media. In “Be a Body” Grimes declares: “Don’t want a man, what a sight / ‘Cause I want to call home / (Be a body) // I close my eyes until I see / I don’t need hands to touch me.” This strikes a strong chord for me with the closing lines of the book’s final poem “Days of Oakland” (with my slightest intervention):

A woman alone is a shuttered garden

Heaped on the edge of a cliff.

The identity of the bridegroom is slowly revealed.

There is no turning back from that [masked] face.

Magdalena Edwards is a writer, actor, and translator from Spanish & Portuguese. Her work has appeared in Boston Review, The Paris Review Daily, Los Angeles Review of Books, The Millions, Rattle, The Critical Flame, Words Without Borders, and Chile’s leading newspaper, El Mercurio. She holds a PhD in Comparative Literature from UCLA and a BA in Social Studies from Harvard. More at www.magdalenaedwards.com and on Twitter @magda8lena and Instagram at @msmagda8lena

This post may contain affiliate links.