[University of Pittsburgh Press; 2018]

[University of Pittsburgh Press; 2018]

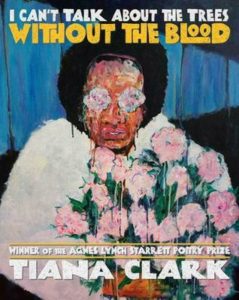

Tiana Clark’s I Can’t Talk about the Trees without the Blood explores an ongoing epiphanic challenge — that we can’t fully appreciate the beauty of the world without also fully acknowledging its pain. To do so the collection offers its readers a range of forms and subjects; it juxtaposes poems that suggest autobiographical narrative against lyrical and persona poetry, often driven by ekphrasis and history, trafficking in inspirations that include Phillis Wheatley, Rihanna, and George Balanchine ballet. Clark’s poems are often place-based, using the American South both as a muse and assailant. Her speakers negotiate the interplay of the South’s past and present with regards to the complexities of race and sexual violence, while assessing possibilities for living in the face of these often swept-under-the-rug inequities. Previously the winner of Bull City Press’s Frost Place Chapbook Competition, this collection represents Clark’s first full-length, winning the 2018 Agnes Lynch Starrett Poetry Prize from the University of Pittsburgh Press.

The book is arranged as a triptych, dividing its full-sentence title into three eponymous sections: I. “I Can’t Talk,” II. “About the Trees,” and III. “Without the Blood.” It often feels like a Russian doll, a box within a box that helps the poet push its polyvocal ends towards harmony. In the opening proem titled “Nashville,” the city becomes a canvas and Clark depicts gentrification and racism at odds with a deep love of place — each haunting and taunting one another and the speaker as they vie irreconcilably for space. The concluding poem “How to Find the Center of a Circle” uses a tripartite columnar structure around the equation to find a circle’s center with known variables on a grid: x2+y2=r2, the form also recalling the three sections of the collection; both the opening poem and the final poem echo the speaker’s experience of being called the N-word, the first more deeply entrenched in narrative, the latter more lyric. Two the most evocative poems to me in this collection were “Soil Horizon,” a three-page poem in the first section, and “The Rime of Nina Simone” a sixteen-page poem that rounds out an ekphrastic sequence in the middle of the collection. These two poems, while not entirely indicative of the more sparse, minimal styles employed in poems such as “How to Find the Center of a Circle,” speak to one of Clark’s distinctive strengths as a poet: the longform.

One of the most memorable lines in the collection appears in “Soil Horizon.” The inciting incident of the piece is that the speaker’s extended family wishes to confirm whether it is “okay” to take their family portrait at Carnton Plantation. As the only black member of the family, she is the only one consulted about the morality of capturing a family portrait on a landscape formerly teeming with the violence of slavery, with the implication that no one else in the family finds that past to be a troubling proposition. Before Carnton Plantation in Tennessee served as the site of one the bloodiest battles during the Civil War with over 9,500 casualties (mostly Confederate soldiers), the plantation fostered the atrocities of slavery and slaveholders being enriched by human property. After the battle, the plantation transformed into one of the largest field hospitals as the Confederate wounded attempted to mend, likely ambivalent and indifferent to those wounded before them by a system they fought to preserve.

Unanswerable questions form a leitmotif within Clark’s style. As excerpts of the inciting conversation with the speaker and her mother-in-law move across couplets, the speaker asks, “How do we stand on the dead and smile? I carry so many black souls / in my skin, sometimes I swear it vibrates, like a tuning fork when struck.” The simile of skin compared to a tuning fork resonated with me, a feeling amplified perhaps by Clark’s sonic choices, ending with the verb “struck,” to create consonance with the fricative k sound that carries throughout (“carry,” “black,” “skin,” “fork,” and “struck” all scanning as the stressed syllables to my ear, contrasting with the more sibilant s sounds). The effect is heightened further by the delay and propulsion across the line break where we pause on “black souls” before moving to “in my skin.” Here, figurative language reaches towards the physical embodiment of feeling, animating words on the page.

This poem works as a window where a reader could glimpse some of the complexity and interiority of one moment of black experience, rendered here as constant moral contradiction, creating a slew of more implied questions — does the speaker risk upsetting her husband’s family? what would the consequences be? does the speaker attempt to educate the white family about the historical context? don’t they already know? or is this one battle, among many endless battles, to forgo? whether the battle could be considered by virtue of being written? if so, does the poem represent surrender or resistance? what does the land remember? — largely, I think the poem helps demonstrate that it depends on who tells and interprets the land’s story and who is there to listen to its story. If so, certain violences will be acknowledged and remembered, others forgotten or marginalized. The plantation, I imagine, is a greenspace now, and like many wooded areas in the South and in the summer, likely in vibrant subtropical bloom. To further borrow Clark’s interrogative device: how does one reconcile these disparities? The collection represents Clark’s open-ended answer.

Nearing the conclusion of the poem, the speaker poses for the family portrait; Clark writes, “I’m staring at the black eye, clutching my smile . . . ” The deliberate diction of “black eye” — resonating with race, violence, and history — suggests the speaker also feels juried by a black audience, represented by the camera that might hope the speaker’s disconnected smile will transform to rage. The poem concludes, “In the portrait, my husband is holding my hand — his hand that dug for bullets as a boy.” The ending image offers closure yet creates an open text, perhaps a horizon of hope and despair. The speaker clutches her smile. Her husband clutches her hand, an act of intimacy despite the seemingly unbridgeable gap of experience and context. The love is as real as the history of violence that dwells in the land. The husband even in the most intimate of gestures is perhaps unable to escape the violence of his heritage any more than the speaker. Still, holding a hand, I suspect, helps.

“Soil Horizon,” at three pages, is lengthier than the typical one- to two-page poem. But it is brief compared to “The Rime of Nina Simone,” a loose riff on Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” which, in its staggered layout and multivalent voices also appears to draw inspiration from (and references) Robert Hayden’s iconic “Middle-passage.” In the poem, the speaker, a poet, is confronted by the ghost of Nina Simone whose inspiration haunts, goads, and challenges her to confront the meaning and intention in her poetry.

Using negative space on the page, Clark navigates and blends voices, with the lyrical “I” of the poem beginning on the left-hand margin, and the contrapuntal voice of Nina Simone interrupting initially tidy and controlled four-line stanza-units with a call from the right side of the page, “Come here . . . I need to tell you something about yourself.” Soon voices toggle for position, yet, we feel who is speaking, and the arrangement creates a more interesting reading experience on the page. The poets’ muse, as many writers can attest, is not always kind. Throughout “The Rime,” Nina is both muse and prosecutor. She berates the poet:

Look, if you can write about anything you want,

Then write. About. Anything. You want.

Why do you keep panting & hunting black hurt

The imagined dialogue is taut and filled with striking, heartbreaking one-liners, like this one from Simone’s voice, further advising:

You have to stay mad

your whole damn life.

The framing device affords the writer and speaker a directness that I often find difficult to plant in contemporary poetry without sounding self-indulgent. It’s not a stretch to say that this long poem becomes the keystone of the collection; it occurs in the heart of the book, contains the collection’s title in its lines, and the gorgeous cover adorning the collection is a portrait of Nina by Terrance Hayes. In his introduction to Best American Poetry 2014, Hayes theorizes that all poems have areas of heat — “a line or two that heats the rest of the poem. A kind of focal point that both anchors and charges it.” If so, it seems possible that this principle might also apply to the reverberations one poem can cause across a collection. I heard Tiana Clark read this poem in its entirety last spring, and it is odd to feel a poem that initially seems so dependent on spacing on the page equally at task in auditory form, if not increasingly so. Lines like “Tell them my body is real — not imagined, / not a prop or sieve or a literary device.” only seemed to build in incantatory power, with performance further bridging the chasm between words like “body” that often risk desensitization on the page, and what these words represent in our physical world. The poem has the power of reverberating and resonating, a tuning fork to the poems that appear before and beyond it.

There is a rare but certain effect I find almost exclusively in the best of poetry — where reading and hearing what is read, literally quickens the reader’s pulse — and this is the experience that found me in Tiana Clark’s debut. To trace this experience is perhaps to trace how the body is shown throughout the collection in frame after frame, with both intimacy and violence, directness and metaphor. Lines like “I was born into the world sideways” push against “Put my hands over / the cage of bones / above your heart.” The notion that pain can feel performative and therefore wrong, or too difficult to express in poems without becoming spectacle, juts against violence expressed in the poems’ form. As Jack Gilbert writes “How astonishing it is that language can almost mean, /and frightening that it does not quite.” As I’ve read and continued to re-read Clark’s work, the chasm between what words mean and the “not quite” blurred until the poems seemed to cut deeper into me; in short, they gripped me and did not let go. This is a debut collection that feels comprehensive and hard-won in its imagination and experience, and its skillful interplay of both on the page offer shining examples of how to create possibilities in contemporary poetry.

Mike Good lives in Pittsburgh. His recent poetry and book reviews can be found in or are forthcoming at The Adroit Journal, december, The Carolina Quarterly, Five Points, Forklift, OH, The Georgia Review, Pleiades, Salamander, SOFTBLOW, and elsewhere. He has received an emerging writer scholarship from The Sun, holds an MFA from Hollins University, and is the managing editor of Autumn House Press.

This post may contain affiliate links.