It’s Copa Mundial time, folks. In an attempt to become more football literate—and, consequently, more European-passing—I’ve been paying pretty close attention to the Cup, particularly to Brazil and Portugal. (I live in Brazil at the moment, and I’m a Portuguese citizen.) Portugal, unfortunately, was defeated by Uruguay, and Brazil lost to Belgium in the quarterfinals. I’ve been encouraging the students at the Brazilian university where I teach to think about football and national identity: does football perpetuate jingoism or serve as an antidote to it? I suggested this topic partly for the selfish reason that I’m not sure how I feel about the issue myself. The inquiry sent me down a rabbit hole of promotional World Cup videos made for various national teams. After watching Brazil’s video and a few others, I came across Portugal’s. I ended up watching it over and over.

The video—entitled “Conquista o sonho” (“Conquer the Dream,” though the makers of the video translate it as “Conquer Your Dream”)—is subtitled, but much of it may not make sense to an English speaker because it’s made up largely of Portuguese idioms. Some translate well: cão que ladra não morda; the dog that barks doesn’t bite. Others fare less well: Mete a carne toda no assador; put all the meat on the grill (basically, “give it your all”).

Most of the video itself is pretty benign. Clips of Ronaldo are mixed in with whoever the hell else is on the Portuguese national team. It’s all vaguely inspirational. There are a few bits in the video, though, that might strike members of the English-speaking world as a bit strange. There’s something vaguely, well, conquistador-ial about the whole video, which—given Portugal’s past—probably isn’t the best look.

Roughly the first half of the video is enshrouded in fog—possibly a reference to a folk tale saying that King Dom Sebastian I, who disappeared in battle, will one day return on a foggy morning to save Portugal. This myth is relatively innocuous in itself, but an extended part of the myth is that when Sebastian, also known as O Encoberto (The Hidden One), returns, he will reign over a worldwide empire that is both administratively and spiritually Portuguese. And then there’s this business of “conquering your dreams.” To be fair, this could potentially be a bit misleading. The verb conquistar in Portuguese can also mean achieve, which means that it sounds far less nefarious in the original. This raises the question, though: at one point in history did the words “conquer” and “achieve” come to be subsumed under the single word conquistar?

Later in the video, a quick image is shown of the Padrão Dos Descobrimentos, a large monument/statue near the Belém area of Lisbon that ostensibly celebrates the Portuguese discoveries. In the video, though, while showing the monument, the video explicitly refers the Portuguese conquistadores—a subtle difference, but a very important one. There’s something slightly off in the way that Portugal memorializes its past, a sort of semantic slipping that any foreigner who has spent significant amount of time in Portugal might pick up on. In the video, pride about the Portuguese discoveries (technically politically innocuous) becomes pride about the Portuguese conquistadores.

This is not to say that Portuguese folks think colonialism is a good thing or even was a good thing, but that pride about Portugal’s exploratory history so quickly bleeds into pride about its colonies that it’s often practically (and historically) impossible to distinguish the two. Few Portuguese folks seem to mind this. Detractors will argue that Portugal’s colonial and Portugal’s exploratory histories are two entirely separate things, that it’s more than possible to be proud of one and repudiate the other. This is not historically true; even a cursory glance at Portugal’s exploratory routes in the 1400s and 1500s shows that most of their efforts, aside from establishing trade routes and diplomatic missions to Asia, were for the purpose of establishing colonies and slavery.

Portugal’s establishment of a spice trade route with India is one of its most strictly “exploratory” (i.e., lacking overtly colonial ambition) ventures. But Portugal began exploring Africa and subsequently installing posts along the coasts specifically to facilitate the spice trade—and, not long after, the slave trade. Which of Portugal’s perambulations can we say were purely exploratory? Madeira and The Azores island were, by most reports, uninhabited when the Portuguese found them on their way to Africa. Perhaps diplomatic missions to Japan and China can also be considered purely exploratory; Portugal is credited with first establishing contact in both places. Perhaps Macau, where “rent” was paid and negotiations were made. Not Goa, which was conquered. Not Brazil, surely, which was quickly turned into a colony and was the primary destination of slave trade transactions along the western coast of Africa. Aside from Portugal’s islands and East Asia, what wholly sanitary, exploratory/adventurer history are we talking about, then?

Portugal’s establishment of a spice trade route with India is one of its most strictly “exploratory” (i.e., lacking overtly colonial ambition) ventures. But Portugal began exploring Africa and subsequently installing posts along the coasts specifically to facilitate the spice trade—and, not long after, the slave trade. Which of Portugal’s perambulations can we say were purely exploratory? Madeira and The Azores island were, by most reports, uninhabited when the Portuguese found them on their way to Africa. Perhaps diplomatic missions to Japan and China can also be considered purely exploratory; Portugal is credited with first establishing contact in both places. Perhaps Macau, where “rent” was paid and negotiations were made. Not Goa, which was conquered. Not Brazil, surely, which was quickly turned into a colony and was the primary destination of slave trade transactions along the western coast of Africa. Aside from Portugal’s islands and East Asia, what wholly sanitary, exploratory/adventurer history are we talking about, then?

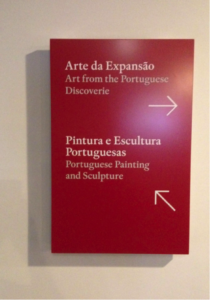

This sort of linguistic sliding is extremely common in Portugal. The photo above is from a museum installation labeled “Art from the Portuguese Discoverie” (typo there), which was really just colonial art. Many of the conversations I had in Portugal illustrated the same—I may mention that my grandfather was in the Portuguese Navy, and then the person may mention that Portugal once had one of the most powerful navies in the world. We’ll talk about the trade routes that Portugal established as far as Japan, a truly remarkable feat in the 1500s. We’ll then talk about the other places that the Portuguese discovered. Eventually, one way or another, we get to the size and grandeur of Portugal’s empire. We’ll spend a while talking about how extensively the 16th and 17th century Portuguese traveled. Sometimes the conversation will veer towards how Portugal was more benevolent towards its colonies than other colonial powers. We might marvel at how international of a language Portuguese is—Portugal, Brazil, Mozambique, Angola, East Timor, Guinea-Basau, Cape Verde, Macau, Goa, Sao Tome, Equatorial Guinea. I have little trouble naming these off the top of my head because it’s a conversation I’ve had so many times.

Even if there were a distinguishable difference between Portugal’s former colonial ambitions and its habit of sailing around the world, I’m not sure Portuguese folks would care. Portugal’s Golden Age is forever part of how it understands its place in the world, and the positive is rather haphazardly combined with the negative in a myriad of small, often frustrating ways.

This is not say that Portugal is at all a bad or undesirable place—if anything, it’s the opposite. Portugal’s immigration policies are far more lax than other Western European countries, and Lisbon is quickly turning into a cosmopolitan tech hub. It’s consistently ranked in the top five most peaceful countries in the world, and, post-bailout, the country’s economic situation has been rapidly improving (under one of the few truly leftist governments in Europe, I might add).

Nor do I think Portugal is at all unique in this regard. Hearing from Spanish people that Spain “brought civilization” to the colonies is relatively common, as is seeing Zwarte Piet (that really strange Dutch Santa Claus blackface tradition). I just don’t think other former colonial powers’ contemporary identities are as inextricably tied to their empires as Portugal’s is, nor do I think that Portugal has been forced to reckon with its colonial past like other larger, internationally important former colonial powers. Aside from the lamentable fact that Portugal is out of the World Cup, the country is in a particularly exciting spot for a myriad of reasons. I just hope this sort of Little Man Syndrome doesn’t become increasingly obvious as Europe’s spotlight continues to shine on Portugal.

Translation: Portugal is not a small country.

Jeremy Klemin is currently on a Fulbright grant in Curitiba, Brazil. You can find other work of his in The Millions, The Ploughshares Blog, and 3:AM Magazine. He can be found on Twitter @JeremyKlemin.

This post may contain affiliate links.