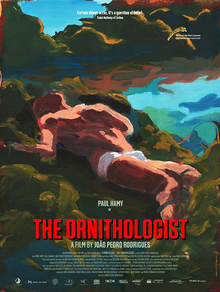

There’s always a theological hot mess or two at the movies in any given year, but 2017 was especially hot and especially messy. The trouble started back in June, when I took the train from D.C. up to Baltimore after celebrating the divine liturgy at my Russian Orthodox parish one Sunday afternoon to catch the only nearby showing of The Ornithologist, a Portuguese film by director João Pedro Rodrigues, known affectionately in some quarters as the Gay Sex with Jesus Movie.

There’s always a theological hot mess or two at the movies in any given year, but 2017 was especially hot and especially messy. The trouble started back in June, when I took the train from D.C. up to Baltimore after celebrating the divine liturgy at my Russian Orthodox parish one Sunday afternoon to catch the only nearby showing of The Ornithologist, a Portuguese film by director João Pedro Rodrigues, known affectionately in some quarters as the Gay Sex with Jesus Movie.

To be clear, the sex happens off-screen, and the film’s Jesus is no only-begotten son of God incarnated by the Holy Spirit, but rather a deaf and mute twink found suckling a goat on the shores of a river by the movie’s titular bird-watcher, Fernando. Fernando has just been through a psychedelic hell to get here. After getting caught up in some rapids upstream and losing his canoe and all his possessions, he was rescued along the Camino de Santiago by a Chinese lesbian couple who drugged him and tied him up, sans everything but his Hanes, in a style reminiscent of the early Christian martyr St. Sebastian (or more precisely, Derek Jarman’s famously homoerotic cinematic reimagining of him).

Fernando slips away from them, narrowly avoiding castration. He’s suggestively visited by a white dove, stumbles into the middle of a pagan ritual, and goes for a light tumble in the sand with Jesus, whom he stabs for stealing his sweater (an oversize olive green hoodie that bestows the wearer with the look, if not the spiritual gifts, of a desert Father). Some Latin-speaking Amazons wielding shotguns ride in on horses from some other movie I would have much rather watched than this one.

Was all of this confounding? Absolutely. Arousing? Frequently. Offensive? Alarmingly, not as much as I would have guessed based on the plot description I just gave. Rodrigues, who by his own admission had no theological upbringing at all and learned about Christianity from admiring the erotic undertones of Renaissance art depicting saints’ lives and Biblical stories, is no Luis Buñuel. For one thing, Buñuel’s anticlerical surrealism is much more entertaining than any of Rodrigues’s heady and languorously-paced escapades. And while Buñuel’s firsthand knowledge of the Church informed his merciless satirizing of it, Rodrigues seems to be genuinely moved by something in Christian iconography. In spite of all its flights of sacrilegious fancy, The Ornithologist’s queering of the familiar forms of the Christian artistic tradition speaks more to the longing for ecstatic, transcendent relationship inscribed on every human heart than to any spiteful desire to blaspheme.

Indeed, Rodrigues is so thirsty for an out-of-body experience that he puts himself in his own film. Though Fernando is played by the French actor Paul Hamy, all his lines have been dubbed over in Portuguese by Rodrigues. In the closing scenes of the film, Rodrigues goes a step further and inexplicably takes Hamy’s place on-screen as well. As far as his direction goes, Rodrigues frequently pulls his camera back from its standard human-sized perspective on the action, as though to pull us out of the immanence of bodily existence. Midway through the first scene, Rodrigues cuts unexpectedly to the actual perspective of a bird’s eye, signified by a disorienting tilt-shift focus and unearthly gliding camera movement. We don’t actually get to see much of Fernando’s tryst with Jesus, either, as Rodrigues tastefully cuts from the opening overtures of their intimacy to that same bird’s-eye view, then even further out to a shot of a distant plane trailing exhaust across a sea-blue sky. Later, as the closing credits roll over the final shot of the film, Fernando (still played by Rodrigues) grabs Jesus—or, rather, his talkative twin brother Thomas (just go with it)—by the hand and skips merrily down the highway outside Padua, growing increasingly smaller on the horizon as the camera stays in place. A perky Portuguese love ballad doubling as a downmarket translation of St. Augustine’s famous dictum about man’s yearning for God (“Our heart finds no rest until it rests in You”) plays over the scene: “You are looking for company / I’m looking for someone / who will be the goal of this energy, / be a body of pleasure.”

By all appearances, The Ornithologist should speak to a Christian like me who’s spent a long time trying to figure out how you’re supposed to configure queer desire in relation to the God you long for and have come to know through a lifetime of worship, study of theology, and life in community with loving Orthodox Christians. But for all his fascination with the aesthetic forms of Christianity, Rodrigues doesn’t consider that those forms could hold any meaning that might be relevant to the questions of queer longing on both of our minds. Has he, for instance, considered that the erotic undertones of all the religious art that so inspired him may be born out of sophisticated theological beliefs about communion and the nature of God’s love for man? The movie opens with an epigraph from a sermon by St. Anthony of Padua preached on Pentecost in 1222—“Whoever approaches the Spirit will feel its warmth, hence his heart will be lifted up to new heights”—but from the raucous and theologically vapid film that follows, it’s unclear whether Rodrigues realizes that St. Anthony is talking about one of the Persons of the Trinity and not the spirit of the dance.

To be sure, modernity has made religious belief more complicated (or at least complicated in a different way) than belief in earlier ages. I begrudge no artist for grappling with tough questions concerning religion—the problem of evil, historic misuses of authority by religious leaders over those both in and outside of their flocks; the usual suspects—and coming away apprehensive or aggressively against the whole God thing. But I am irritated that so many contemporary artists can’t be bothered to do any grappling at all. Too many artists, and filmmakers especially, won’t treat theological traditions as anything other than window dressing, an aesthetic adornment not worth reading too much into.

By that token, Darren Aronofsky’s mother! makes for a strange yet compatible bedfellow with The Ornithologist. It’s a decidedly less queer movie (Michelle Pfeiffer does add a welcome shot of camp), but it’s likewise motivated by concerns that have been the subject of rigorous interrogation by the very religious traditions it so gleefully lampoons.

By that token, Darren Aronofsky’s mother! makes for a strange yet compatible bedfellow with The Ornithologist. It’s a decidedly less queer movie (Michelle Pfeiffer does add a welcome shot of camp), but it’s likewise motivated by concerns that have been the subject of rigorous interrogation by the very religious traditions it so gleefully lampoons.

For its first hour, mother! plays like a greatest hits CD of all those scriptural stories Aronofsky expects you to have forgotten since your days of parent-mandated religious education (Now That’s What I Call Genesis!). Ed Harris, Pfeiffer, and Brian and Domhnall Gleeson show up unnamed and uninvited at the house of odd couple Jennifer Lawrence and Javier Bardem to winkingly reenact familiar scenes from the lives of Adam and Eve and Abel and Cain. (Are Bardem and Lawrence supposed to be God and Mother Earth in this allegory? Who knows, and who cares.) The first half of the film culminates in a “flood” of mild Biblical resonance when some other uninvited houseguests snap an unbraced kitchen sink off the wall and break open a water main.

For the folks playing along at home, the life of Abraham is due up next on the jukebox. But the film veers off in a different, and more prophetic, direction from the free-associative parody of its first half. Lawrence gets pregnant, and Bardem gets some artistic inspiration. Bardem’s a poet—since the movie’s vague enough on the details of his creative output, I’m choosing to believe he’s more of a Khalil Gibran than a Dante—and his latest work captures the hearts and minds of readers the world over. All sorts of religious undertones persist through the rest of the film, but they’re more enlightening about the director’s anxiety over the crumbling state of world affairs than about any actual religion’s methods of thinking through the same. Self-care routines look different for everyone, but only Darren Aronofsky would charge $15 admission to his.

Soon enough, seemingly all of humanity has shown up at the house, clamoring for Bardem’s autograph and blessing or both. The house quickly goes to hell in a handbasket. A distressed Lawrence turns one corner to find a line for the bathroom stretching down the hall and out the front door; she turns another, and there’s Kristen Wiig executing a row of blindfolded prisoners ISIS-style on the living room floor. (You know how it always goes with religious people: in the morning you’re telling a creation story, by night you’re killing non-believers in its name.) Granted, mother! is an aggressively impressive feat of filmmaking, and the movie’s biggest fans seem to have made their peace with the film’s offensively in-poor-taste final five minutes by interpreting the whole exercise as a roller-coaster ride for the senses. But given the seriousness of the topics Aronofsky is playing around with here, why shouldn’t we treat his film as something more than a mere carnival ride?

mother! may be most easily read as a political allegory (Aronofsky himself seems to thinks so) about the destruction of the earth that humans will inevitably wreak when left to their religious devices. (Forget that God’s decreeing the created order good in the opening of Genesis has been ample enough reason for plenty of people of Abrahamic faith to oppose the wanton exploitation of the environment and all beings living in it that mother! posits as the inexorable result of mankind’s worshipful urges.) Regardless, the movie’s underlying theology is still worth pondering. The entire film is shot either from Lawrence’s perspective, from directly over her shoulder, or directly facing her. Compared with The Ornithologist, it’s a movie that revels in the immanence of mankind’s embodied reality. The sounds of this movie fiendishly assault the ears with greater intensity and precision as the show rolls on, until you too are trapped in the immediacy of the godforsaken nightmare poor Jennifer Lawrence eventually finds herself living in. Likewise, the camerawork admits of no transcendent maneuvers. Doing so would ruin the perverse fun by relieving us from Lawrence’s harrowed perspective, though aesthetically speaking, it would also betray the film’s atheistic conviction in man as the ultimate arbiter of his own justice until nature one day decides to shut the party down.

If there is no transcendent God, as the movie seems to posit audiovisually, or if there is but he isn’t loving (a reading that’s opened up by a wry revelation about Bardem’s character in the conclusion), then is this pile of hot nonsense really the best Aronofsky can come up with in the circumstances to confront such age-old problems as mankind’s unjust stewardship of the environment, violence against women, religiously-motivated terrorism, and the obstinate success of artistic charlatans? And if there is a loving God, well, then wouldn’t it be in our best interests to learn a little something about him and adjust our response accordingly?

I suspect that this kind of movie, intrigued by religion from a distance, will keep getting made so long as politics remains the framework readiest at hand for viewers and artists alike to make sense of the world and the people who go about believing things about its maker. But why should we settle for that when it’s never been easier for artists to learn a little more about the religious sources of their inspiration before getting to work? Whatever their sensual pleasures, movies like The Ornithologist and mother! are too noticeably constrained by their authors’ incuriosity about the richness of others’ religious beliefs to be the powerful works of art their makers so clearly intend them to be. If these artists are content to keep playing with Play-Doh, then that’s their prerogative. But the door to the ceramics studio is still unlocked, the kiln can still be fired; the potter’s wheel is all set up, waiting patiently for a sculptor to come and work the clay.

Tim Markatos is a writer and designer who lives in Washington, D.C. More of his stray thoughts on film and religion appear in Fare Forward, The Weekly Standard, Bright Wall Dark Room, and his newsletter, Movie Enthusiast.

This post may contain affiliate links.