The young men and women of the high reaches of ice devised a party for themselves. In a very cold freeze, a group of ten or twelve gathered in one boy’s father’s barn. In amongst the smells and shuffling of the livestock, the girls dared to unwrap the bundles they’d become. As they watched them do it, the boys tried very hard to breathe, then they themselves quickly remembered to follow suit. Without those many layers, all of them were like pupae, naked in a new skin. They pretended it was summer, very far away, that one of them might, at any moment, break into a sweat. The boys fanned the girls; the girls blew cool breezes into the boys’ ears. One girl, at the height of all this merriment, fumbled through her discarded parka. She found the dimpled orange globe she had buried there. When she ripped the skin, tore it off in one long, curling piece, the smell — that of a faraway, foreign summer where things are light and sweet and very warm — filled the barn. The rose-fleshed girls and the scrawny boys watched, rapt, as she took the sweet sections, one by one, into her cold mouth.

—“Arctic Circle,” TJ Beitelman, Communion

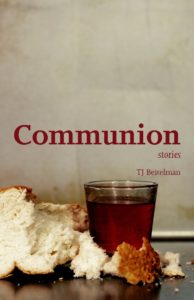

This piece opens TJ Beitelman’s finely detailed and moving short story collection Communion, as a closely observed vignette, a poem, a memory, masquerading as a short story, inviting the reader into the warm, soft scene. The girls and boys navigate together (togetherness and separation are prevalent themes in Beitelman’s work; more on that later) the especially alien place between youth and adulthood. The girls here are scarcely more mature, unwrapping themselves openly in plain sight, as the boys are rendered still, frozen, stuck in breathless observation. The whole group is helpless and stilted as they watch the orange-eater sensually tasting the forbidden fruit, in a display of budding adulthood — momentarily, or permanently — realized. The quiet, gentle tone and the delicate confidence in which the themes are proposed, and the themes themselves (individuals and groups looking for a form of escape; a yearning for intimacy, and closeness; personal isolation) expressed here are indicative of the entire collection of stories that follow.

Renowned short story writer Raymond Carver ambles through the stylistic proceedings like a ghost, like a piece of music quietly playing in the background. Both authors explore the theme of solitude, though Beitelman is a kind of kinder Carver, the flow of his sentences more fluid, elongated, moving. An early example of this general similarity occurs in “Vows,” detailing a tense exchange between an unnamed man and woman as they make a long drive home from visiting his mother. A disagreement occurred between the two during the visit, which we’re only made privy to through their dialogue. The discord between them is laid bare in spare language:

–I just want to know why you said what you said. He did not take his eyes from the road.

–I haven’t said a word for ninety minutes straight, she said.

–You know what I mean. What you said about the light coming in the window in the morning.

—My god that was Wednesday.

—It was Friday.

—Wednesday and Friday are the same thing, nearly.

—You’re not going to tell me why you said it, are you?

–I’m almost positive I don’t know.

And that was it for a long time.

A requisite stop for refueling, and a bathroom break for her, invites a wolf-whistle from one of a group of men loitering at the station. The couple departs, though not before the man raises his middle fingers in plain sight to the group in frustrated response. He and she then depart.

Still distant, a moment of contemplation occurs for her as she observes the sky at dusk, as their trip home resumes:

The last act of this particular gray sky was to break into an astonishing range of reds and yellows and oranges just along the horizon line. She found that she had — almost without meaning to — placed her slim pinkie finger on the cool, flat passenger’s side window. The unselfconscious gesture of a child. Though it was, of course, impossible, she wanted to somehow touch these bright colors that had burst from nowhere and nothing.

A car chase soon ensues, the couple on the receiving end of somewhat predictable and mild violence, with no physical harm. Yet the strain and stress of their relationship glimpsed earlier inevitably, and undoubtedly, ushered in these acts. The couple, by the end, is either united, or driven further apart by the experience — it’s not clear — as they move “forward into what had become a vast but simple darkness.” Is this a black pit or void, mirroring their own emotions, or indicating a peaceful resolution? Regardless of the ultimate meaning, it stands in sharp contrast with the colorful passage above.

A truism for Carver is also one for Beitelman, that becomes inarguably evident the more it is repeated: Our relationships with others do not quell our inherent loneliness — they only amplify it. In our aloneness, we stumble towards affection and affinity, failing and falling with each step. We have only moments of transient connections. Beitelman’s stories reflect and refract these themes as if in a prism, eyed up-close, delicately. These two themes — loneliness and aloneness — also pervade the sensitively told, “Sister Blanche.” A closer reading of just the title subtly suggests themes explored in more depth as the story develops. Blanche is the virginal narrator and the actual sister of Cheri. But yet the use of “sister” implies Blanche shares the same habits as a Sister of the Catholic faith: quietly living a solitary life of vows: of poverty, celibacy, and obedience. Blanche describes their differences in appearance, and disposition,this way:

My sister is still an attractive woman in many ways — her skin is smooth, her nose is a button, and her small breasts have made good use of their advantages against gravity. I, on the other hand, have never been pretty, and I am small and stocky, with a ruddy face and short, graying red hair. This — the contrast between my pretty sister and me — is the way it has always been.

Based on this unflattering comparison , Cherie is obviously the more attractive of the two, still a player in the relationship game; Blanche already in retirement. They embark on an inauspicious trip from Massachusetts to Vermont to meet Cherie’s beau of the distant past, now widowed, who she believes will become her husband — note: her biological clock is ticking. Instead, in his own safe way, he falls for Blanche, sending her many lengthy letters afterwards — a secret Blanche wisely and respectfully keeps from her sister. This clandestine, one-way correspondence promotes a slight shift in Blanche’s life, where, as she says, she generally chooses to seek only comfort. She permits herself reflection in her isolation, arriving at the conclusion that “ . . . as if for the first time, I am aware of an unavoidable and comforting truth about the world. Most things do not take root, and that is as it was intended.” And the characters in these stories consistently struggle to place their own roots.

Beitelman repeatedly writes in a genuine voice, the characters speaking as flesh-and-blood people,across the stories, as they generally strive to find their own version of peace through whatever means of escape are available to them. “Ruin” depicts a divorced middle-aged man, Jim, coming to terms with dating a younger, attractive woman, Nicole. His past is never far behind, as he recalls his first broken marriage and other failures. The city of Mobile, Alabama serves as a stage and setting for the events to occur, as if a minor character.

After an evening of making love, the next morning finds Jim vulnerable, staring at Nicole as she drops the sheet covering her body, and passes naked into the bathroom. She leaves him alone in bed, reflecting: “I see her silhouette — long and thin and ageless — and I forget who I am, who she is, or why exactly we are here.” Forgetting is a form of escape, but only temporarily. And even by the end of the story, Jim is left in the vague and muddled middle ground between remembering and forgetting.

But just as Blanche described the evolution of her private life as a small point of pride since she retained her integrity, “Come to Jesus,” a later story, details a man whose high school sweetheart wife left him, since he did not properly fear God. “From the very start, Jesus would not take root in me,” he says. By story’s end, he succumbs at a revival, right on stage, falling backwards to be caught safely by a large man’s “meaty hands.” The spirit of religion, in this case, serving as a different means of escape.

Once readers arrive at the final two stories, the collection feels as if it’s been driving towards that destination the whole time. The first, “Hope, Faith, and Love” is broken into seven smaller parts, each a set piece told in chronological order, like well-written journal entries composed many years later. Details of the narrator’s experience as a child are shared, the difficult life endured by his siblings. Their father is perceived and portrayed as an imposing deity; mother is worn down and worn out; and a newborn sibling is cast as a Christ figure, all set in relative squalor — you can feel their hunger.

By the end of the last section, “Charon’s Boat,” their father is reduced to a powerless and feeble man, frozen in a catatonic state. The children, realizing their opportunity, escape in the family’s aged and maligned Gremlin, the Charon’s Boat of the title. One hopes they’re off to a better destination, but for Beitelman, the escape is its own reward.

“Communion,” the brief closing story, gives the mother her moment, as the narrator grudgingly helps prepare crab cakes with her, the two together. The recalcitrant assistant is dismayed by his mother’s form of celebration and memorial for the deceased father — producing single drops of her own blood, christening the individual cakes, in a homegrown version of the Eucharist.

While the collection is strong, there are scattershot moments where Beitelman occasionally approaches sentimentality and melodrama. The multi-part, sophomoric “Sangha” reaches for a profundity it can’t fully grasp. The single-paragraph, “Masks,” is the less successful twin to “Arctic Circle,” and “Blackface” never resolves its intriguing set up, where the adult lives of mother and son oddly intersect at a moment when they are at their most vulnerable and desperate. The broader implications beyond the initial setup of their intriguing and extreme circumstances is left unexplored.

In fact, the entire collection treads lightly as it risks slipping into melodrama or sentimentality, and each is an exaggeration: one an appeal to emotions, the other an excessive expression of those emotions. But these minor improprieties are easily forgiven. Why? Because the ceremony of religion requires it. A moving church service shares the same qualities as an effective short story. Beidelman recognizes the power of both to engage another.

The religiosity inherent in the work is introduced as subtly as the girls whispering into the boys’ ears in the opening story. Let’s be clear: readers should take the title of the collection — communion — as a literal missive regarding Beitelman’s intentions. The characters that populate the worlds he creates and explores seek above all else to share in a significant and meaningful exchange, of intimate thoughts and feelings, with spiritual and meaningful implications, with or without establishing roots.

Broadening the definition further, Beitelman includes the solitary and private act of reading — and the relationship between author, the work, and the reader — as a form of communion itself. Beitelman offered this in a recent e-mail exchange: “These stories are in communion as, always, is the author and the reader, Creator/Creation, etc. It’s always a back and forth. I’ve been thinking a lot about the Michelangelo mural on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, Adam reaching for God. Or is it the other way around? Stories are that. A transcendence and a coming down to earth. A thing created and consumed. All at once.”

And the “all at once” best captures how these stories should be consumed by the reader. Read them in a couple of sittings, take them in as you would a play, a piece of classical music, or a film. Read them as a continuous string for greater impact, emotional depth, and resonance.

An intimacy then perhaps is established, at last.

Ray Barker is the Chief Archivist/Librarian at Glenstone, a modern art museum in Potomac, Maryland. His work has previously appeared or is forthcoming in Music & Literature, The Collagist, Heavy Feather Review, The Los Angeles Review, 3:AM Magazine, and Gulf Coast. He lives with his wife and daughter in Washington, DC.

This post may contain affiliate links.